Ivan Zhukovsky

“On her nose, a red star twinkles”: a brief history of Moscow river transport

V–A–C Sreda online magazine presents a new three-month program dedicated to water and its meaning in culture, art, and folklore. The first issue features a text by journalist Ivan Zhukovsky on the history of river tramways and the role of water transport in the tenth–thirteenth centuries, when rivers were considered one of the main transport arteries of Rus’.

In his study, the author not only examines the economic and political function of rivers, but also finds curious links in literature, referring to diary notes of Mikhail and Elena Bulgakov, a short story by Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov, archival materials and memoirs, as well as explains the origin of the word “tramway” and its diminutive form “tram.”

River trams (singular: tramvaichik, plural: tramvaichiki) have always been an incomprehensible phenomenon to me. I was born in Saint Petersburg, where sailing along the canals was ordered by Peter himself, and when I was five, I was taken to ride on a river tram—for fun. Seeing and hearing the impudent barkers of invitations by the pier at Anichkov Bridge, I came over all shy. The excursion itself, however, I liked—it was unusual to look at the city from such an angle, sitting on a bench below the open sky, right in the middle of the river.

Afterwards, I was bothered by the name of these ships… What did it mean? “Tram-vai-chi-ki…” But they don’t run on electricity, they don’t ring, they don’t have rails, and they don’t carry passengers from stop to stop! As a child, I wasn’t just curious, but also rather forgetful, which meant that I only remembered about the river trams again around twenty years later, when, already living in Moscow, I was riding along the Moskva River on a bicycle and noticed not my curiosity, but rather my irritation at the impudent barkers near the numerous tram piers.

The question of why the word tram-vai-chik is used to refer to river transport continued to puzzle me. Giving the newspapers a cursory leaf-through, I saw it alleged everywhere that river trams had only appeared in Moscow in 1923. And with half an ear, I heard that the city authorities wanted to relaunch river passenger transport in 2023. The date stood out as suspiciously round. Whether archness or accident, or just a lack of curiosity—I didn’t know, but a funny feeling within me told me that the Moskva River had been used for the transportation of passengers of business and leisure long before the revolution.

And so, I decided to dive into history.

“Long has Rus’ walked these paths”

Geographically, it so happened that river transport in Russia was more significant and developed than land communication. During the time of the Varangians, from the tenth to the thirteenth century, it was rivers that allowed for the fastest travel across the giant plain of impenetrable forests. Goods (“native products of Rus’ included bread, honey, and fur”) were transported along rivers—on the boats of princes with their retinues and overseas ambassadors, and on the plow boats of migrants fleeing to new places from hunger and the raids of the Polovtsians and Khazars.

“Russians have long crossed from the upper reaches of one river to another, carrying their goods and dragging their ships. Just as the entire course of trade movement of ancient Rus’ was closely dependent on mutual rapprochement in the upper reaches of rivers, so the forward movement of Russian statehood depends on that same phenomenon,” states the Russian historian Alexander Nikolaev in his 1900 Brief Historical Sketch of the Development of Water and Land Communications of Trade Ports in Russia.

The Moskva River was used both for navigation and for timber rafting, and generally ensured the provision of all necessary goods to the “new ‘Mother’ of Russian cities.” [9:14] From that time, writes the author of the Brief Historical Sketch, river routes ceased to be the main and single transport routes, and began to gradually share their significance with land roads.

Nevertheless, river transport was more convenient in as far as travelling by land was dangerous and expensive—rivers were cheaper, calmer, and one could travel along them year round, changing from boat to sleigh in winter. The Moscow principality and later the Russian tsardom should, without the slightest doubt, be considered to have been a river- rather than sea-faring power.

“All the advantages were on the side of river roads, and the government diligently ensured that the river routes remained opened and that private owners did not block river roads” remarks Nikolaev.

And if it was not just wild animals, but also robbers that lay in wait for travellers and merchants on the open roads and in the forests, then rivers were safer. And although robbers could also lie in wait on river routes (for this reason, caravans of ships were often sent on their way under the protection of armed infantrymen), it was much easier to make away on the water.

“There are enough such steamboats running”

Throughout the history of Russian water transport, “river tramvaichiki” have had different names—they were often termed “steamers,” though “filyanchik,” a distortion of “Finland” from the name Light Shipping Society of Finland, which owned river transport in many Russian cities before the revolution (excluding Moscow), was also in use. There were many other words to designate river passenger ships, but for some reason, all were diminuitive-endearments—clearly, they were loved.

The word “tram” itself appeared in the Russian language at the beginning of the 1900s, when the first land trams were launched in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. One of the first times the English word “tramway” appeared in Russian was in the diaries of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Admittedly, Tchaikovsky used the word in its English variant—tramway, and not in Russia, but in Florence: “Trial holiday “Tramway” trains [steam trams]. Lessons. After dinner all the same boring rigmarole. Never has Florence been so vile to me during this stay as it was today.”

Later, trams appeared in Russia, and the word “tram” Russified and firmly settled into the language. This said, the concept of a “river tram” is characteristic only of the Russian language—in other countries, similar ships are called “water taxis” or “water buses.” In general, this is a ship powered by a fuel motor used within a city for passenger transport. And this transportation, naturally, is not free.

At first, they sought to entice Muscovites to use river transport through advertisements that described the features and advantages of boat rides.

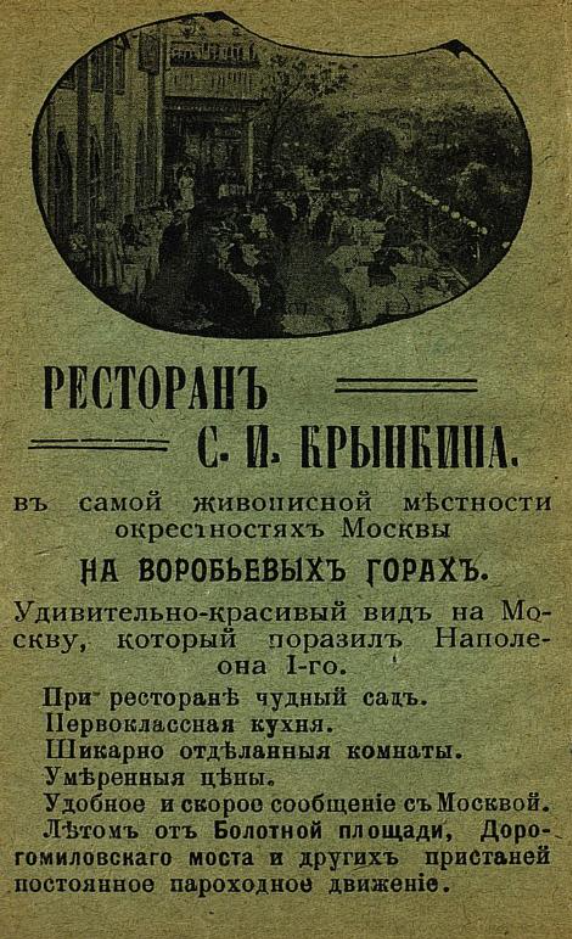

“Krynkin’s restaurant, in the most picturesque area in the environs of Moscow, on Sparrow Hills. Remarkably beautiful views over Moscow that amazed Napoleon I. The restaurant has a marvellous garden. A first-class kitchen. Luxuriously decorated rooms. Moderate prices. Convenient and fast communication with Moscow. In the summer, there is constant steamboat traffic from Bolotnaya Square, Dorogomilovsky Bridge, and other piers”—this was the kind of advertisement with which the 1910 guidebook A Ride Along the Moskva River opened.

This guidebook was written by Pyotr Alekseevich Olenin-Volgar (1846–1926), a man whose biography is deserving of an article of its own. He was not just a writer and a poet, but also an actor-tragedian, a traveller, a sailor, an artist, and a journalist—in the words of the Soviet writer Konstantin Paustovsky, “a man of faeric life.” And he also did not shy away from what is now called “copywriting.”

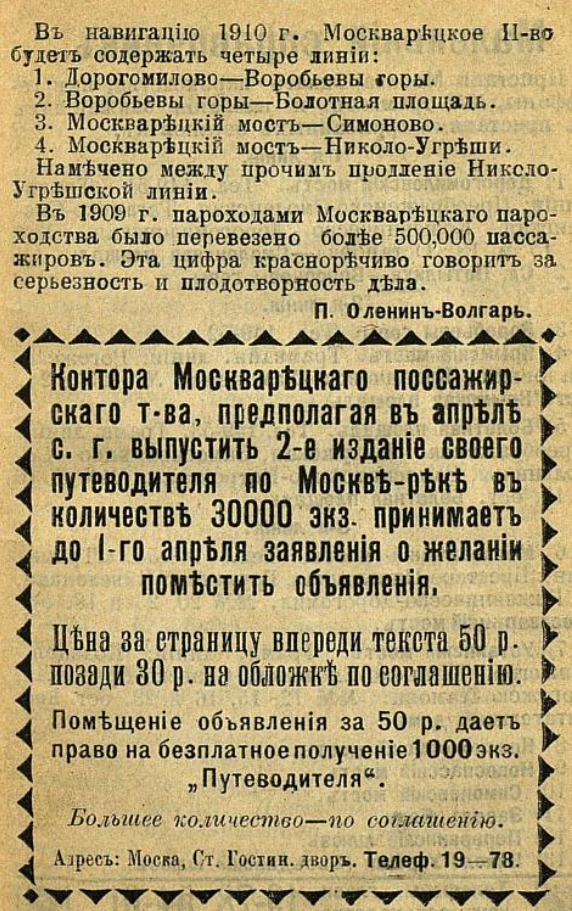

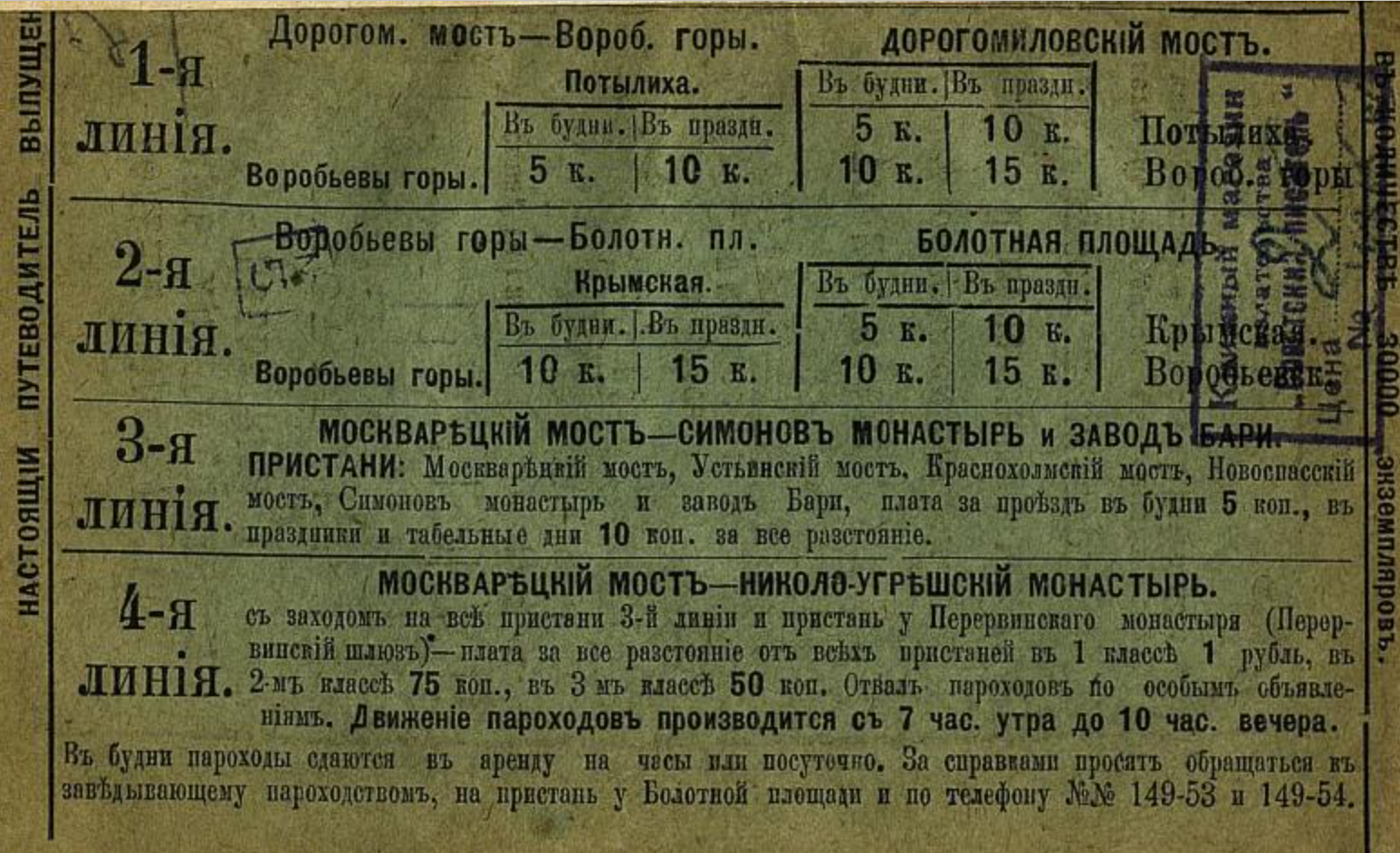

The guidebook was ordered from Olenin-Volgar by the Moskvoretsky Passenger Shipping Company of the Okunev merchant brothers. In this minute book of fifty-five pages, of which thirty are devoted directly to the guidebook text, and more than a dozen to various advertisements and reference information, the author remarks that in 1910, along with the usual land routes, an idle Muscovite has another “more accessible in material terms and far more interesting” entertainment available to them—a ride along the Moskva River in a small steamboat (not yet a tram).

“There are enough such steamboats running, and Moskvoretsky Passenger Shipping Company runs a number of lines. Rides are very cheap, and riding along the beautiful river provides the opportunity not just to fall in love with the views, but, as the steamboats go far beyond the city, to the Nikolo-Ugreshsky Monastery, to breath fresh river air,”—adds the compiler of the guidebook. [14:3]

The Moskvoretsky Passenger Shipping Company belonged to the Okunev merchant brothers, Ivan and Nikita Potapovich. In the Moskva River guidebook, the last chapter is dedicated to “public relations”—in it, the writer, Olenin-Volgar, not seeking praise, paints the virtues and merits of the “shipping magnates” who had paid him for his work.

One learns from this chapter that “for a long time”—from the 1870s to 1902—the Moskva River was in “foreign bondage, the water artery rented by a French shipping company.” [14.30] Under the French, passenger river transport “was somewhat haphazard, and steamboats would only go to Sparrow Hills, and without schedules at that.” [14] But with the Okunevs, Olenin-Volgar goes on, matters stood differently:

“Their eyes having been trained in the river business, they could not but fail to see the dire need for a passenger shipping company on the river that crosses the vast capital. They energetically got down to business, formed a friendly company, and formed…a shipping company.”

It is worth noting that the aforementioned Partnership of the Moskvoretsky Touring Shipping Company built Moscow’s system of floodgates with French capital between 1874 and 1877, thanks to which much of the navigation on the Moskva River is ensured to this day. However, this concession allowed the French a monopoly on river transport right until 1902. It was for this reason that at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century the river was not used for regular passenger traffic.

However, by 1906, the Okunev brothers had three steamboats and seven ships powered by Swedish oil engines running on the Moscow lines. That is, it seems to me that passenger ships—river tramvaichiki—have been running on the Moskva River for more than 117 years. The Okunev brothers’ own shipbuilding was also developing then—in 1907, a number of Okunev ships were built in Russian shipyards—for example, the “Nikita Okunev” motorboat was built at the Valenkov plant in Murom.

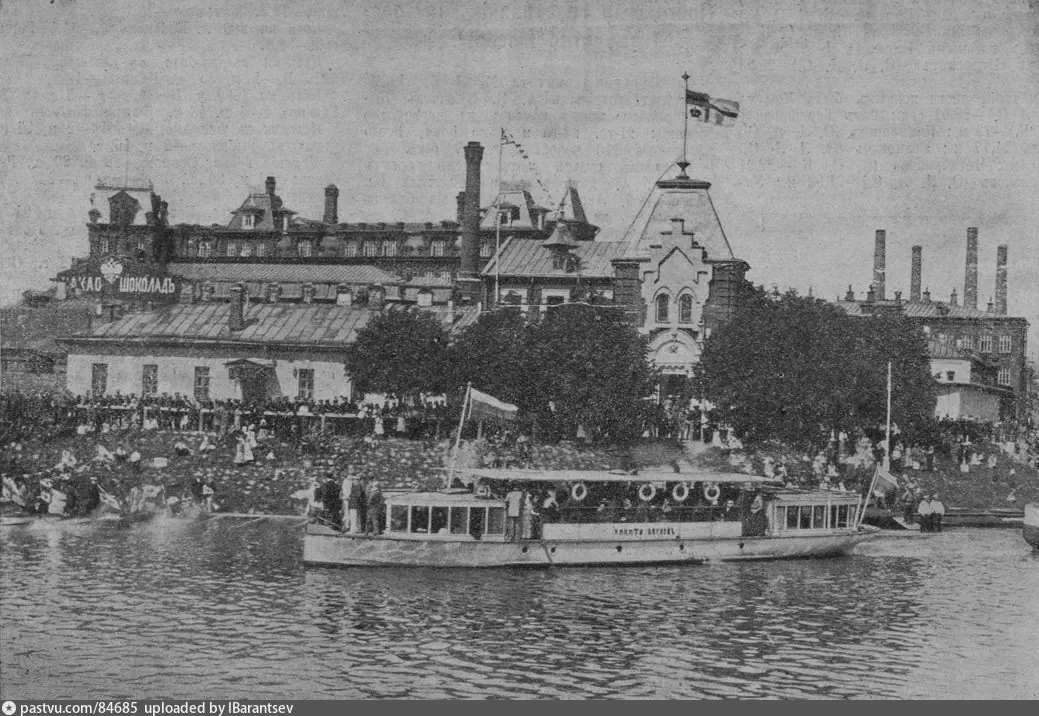

In Moscow, in only the navigation of 1910, four steamship lines were opened within the city limits. A year before, in 1901, the Okunev brothers’ shipping company had, according to their own statements, been used by half a million passengers. [14:31] It is not insignificant that the prices of tickets were accessible—a trip within the city cost only 5–10 kopeks. And the Okunev ships ran from early morning until late evening. Judging by an accidentally found photograph, the Okunevs also had their own steamboat—very similar to modern river trams, with glassed cabins and curtains. And even the advertisements on the roofs were somehow reminiscent of contemporary tramvaichiki.

The co-owner of the shipping company—the merchant of the second guild Nikita Okunev, who would go on to be known as an employee of the capital’s Airplane Shipping Company—kept a diary for a long time, which has been preserved to our days. 1919 sees Okunev note, remembering his old life, how once upon a time the transport “crowd gathered on Sparrow Hills [in the restaurant] at Krynkin’s, where they even went on their “own” steamboats. [12]

“Life has become better, life has become happier”

Little about the state of the Moskva River following the 1917 revolution has been preserved and, until 1923, very little is known about passenger transport. However, Nikita Okunev did record an important testimony at the beginning of 1918:

“Decree: All shipping enterprises belonging to joint-stock companies, share partnerships, trading houses, and sole proprietorships along with all movable and immovable property, assets, and liabilities, are declared the national, indivisible property of the Soviet Republic.” [12]

Okunev also notes that the Moskva River had frozen in winter, and that, as in old times, people had ridden sledges along it.

In almost all modern articles about the history of Moscow river transport, it is held that the first Soviet river tramvaichiki appeared in the Russian capital in 1923, exactly a hundred years ago. Reliable confirmation of this is difficult to find, and, clearly, the problem has roamed from text to text since 1986, when the assertion that “in Moscow, [river trams] began running on the river lines in 1923” appeared in the magazine Technology for the Youth. [12] The history of the Okunev brothers’ shipping company was forgotten for a long time.

In terms of public transport in the capital of the young Soviet republic, there were only land trams until the mid-1920s, and there was not even enough money in the budget for their serious development. The tram routes that had existed since tsarist times were clearly unable to cope with the rising flow of passengers.

In December of 1924, Mikhail Bulgakov, who was then living in Moscow, described the state of public transport in the city. A former doctor, he compared it to gangrene. What can river trams possibly have to do here![1]

“Moscow is in the dirt, and more and more alight: two phenomena are in a bizarre coexistence: the improvement of life, and its utter gangrene. In the centre of Moscow, beginning from the Lubyanka, Vodokanal have carried out test drilling for the metro. This is life. But the metro will not be built, because there isn’t any money for it. This is gangrene. A plan to control traffic is being developed. This is life. But there is no traffic, because there are not enough trams—it is ludicrous, there are eight buses in all of Moscow.” [3]

Four years later much, of course, had changed, but it was also as though nothing had changed at all. The Soviet writers Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov wrote in 1928: “Moscow trams are incapable of serving everyone, but somehow still function. It is a miracle, and like any miracle, it goes against a materialistic worldview. And for this reason, it falls upon representatives of public utilities to eradicate miracles in urban transport. For this, one needs to add more carriages. Overload them to the point that their glass breaks, the carriages, with a heavy roar, disembark their workers…” [8]

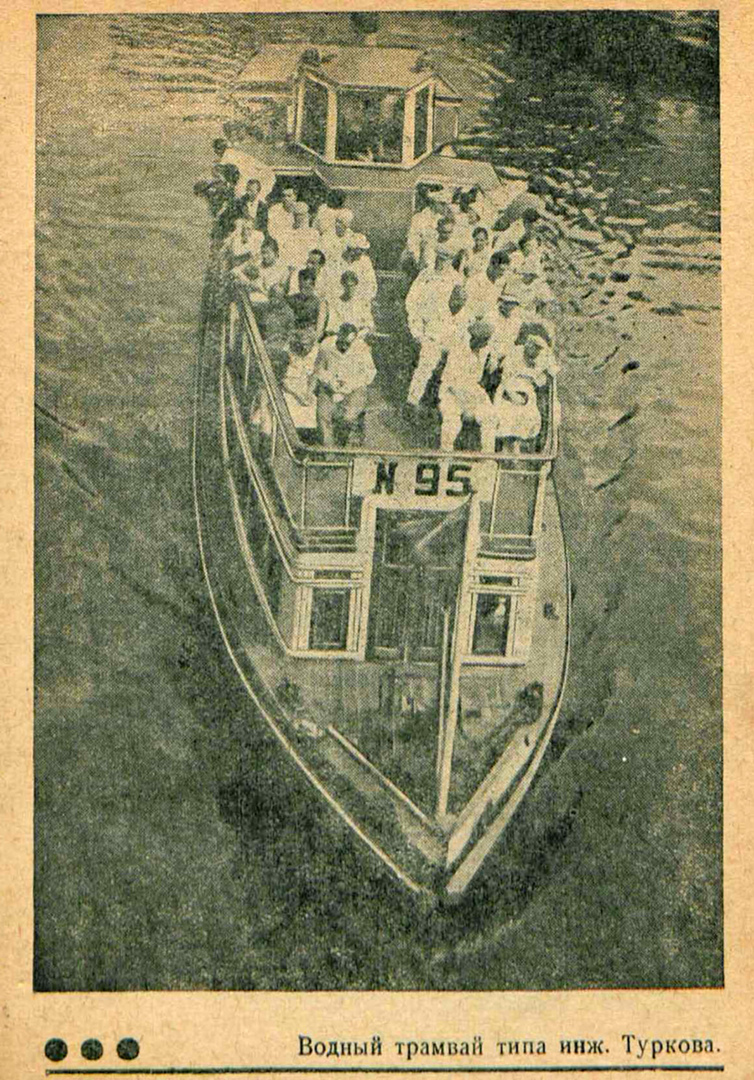

Yet one way or another, Technology for the Youth tells us that Mossovet—the main organ of city administration—decided in the early 1920s to launch a “new” and more economic mode of transport along the Moskva River, in order to take pressure off the tram lines. The benches on the decks were exactly the same as those in the land trams, which is where the people’s name—“river tramvaichik”—has its origins. At that time, the state-owned Moscow Suburban Shipping Company was responsible for passenger transport.

The water trams of those years were boats that could accommodate several dozen passengers, and they had a shallow draught, as they had to be able to moor not just at disembarking stations and piers but directly to the shore. Moscow’s embankments had been lined in granite since tsarist times, but this was far from being the case everywhere—in Khamovniki and near Sparrow Hills, the banks were gentle slopes until the 1930s, and the river often burst its banks during spring floods.

Organised movement of river trams in Soviet Moscow only began in 1931—until then, movement was “sporadic.” [10] But by the first half of the 1930s, water transport was running along the Moskva River very actively. The number of steamboats and their size, in comparison with the 1920s, had certainly grown with time. And propaganda could not but pay attention to this.

We meet the tone characteristic of that period in a guidebook to the rivers of the USSR published in 1937:

“Life has become better, life has become happier—and this is also felt on steamboats. […] The Russian aristocracy, the big bourgeoisie, and the landowners did not like to travel around Russia. They preferred expensive trips abroad to to trips in Russia. And their journeys there made up a scandalous chronicle, so rich in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Monte-Carlo, Nice. Russian bourgeois tourism was a means of somehow filling the void of parasitic life.” [13: 3] Further—a quotation from Evgeny Onegin (in 1937, the USSR celebrated the hundred year anniversary of Alexander Pushkin with great fanfare—author’s note) about boredom.

Before the revolution, according to the guidebook, steamboats were principally used for the transportation of prisoners and convicts, while peasants and workers would travel only “in search of work, pieces of bread, from prison—to exile.” Curiously, the guidebook remarks enthusiastically that after the revolution: “thousands of Soviet people crossed the vast expanses of their great country on planes, ice-breakers, cars and gliders, bicycles and kayaks, and lastly on foot… to get to know their Motherland, transformed under the rule of the leader of the peoples the great Stalin into the most happy and flourishing country of the world.” [16:11]Though there were also some unhappier cases. For example, in 1936, the Pravda correspondent Lazar Frontman described in his diary a conversation he had with Sergey Bryukhonenko—a Soviet philosopher and the creator of the world’s first heart-lung machine—in which Bryukhonenko recalls how “once they brought him seven corpses, drowned in a river tram accident.” [2] A rare but chilling event.

In the case of river tramvaichiki, however, good and unfrightening memories were significantly more prevalent. In the 1930s, Mikhail Bulgakov and his wife Elena—the preserver of his literary heritage—were not troubled by problems of public transport. The Bulgakovs were worried by the arrest of their acquaintances and problems with the staging of plays written by Mikhail Afanasyevich. Bulgakov himself, among other things, was sad that “he would never see Europe.” On April 29, 1937, Elena also worried about the future, which, she wrote in her diary entry for that day, was “truly pitch-dark.”

But then, on April 30, Elena notes in her diary: “good, sunny weather, we rode on the river tram along the Moskva River.” The trip calmed the writer’s wife. [6] In the evening of the same day, Bulgakov himself “cheered up, recounted funny things” when friends came to visit them.

In the spring and summer of 1937, Mikhail and Elena Bulgakov took trips along the Moskva River several times. On the evening of July 6, they rode on a river tram to Park Kultury. “There we watched a number—the riding of motorcycles along sheer walls. Scary.” [6] That same evening, Mikhail Afanasyevich went to the Metropol restaurant, but his wife stayed home—she was unwell. [6] A few days later, Elena noted that the water in the river was “awfully dirty.”

September 23 saw the Bulgakovs once again board a boat which carried them along the Moskva River. The day before, Mikhail Afanasyevich had once again been very worried and arrived home with headache. “We went for a ride on a river tram in the afternoon—it calms the nerves. The weather is beautiful.” And the next day—the same, but it was already “foggy and drizzly.”

In that year, Bulgakov was writing a lot—the libretto to the play Minin and Pozharsky, as well as Peter the Great, Theatrical Novel, and The Master and Margarita.

In the end, in The Master and Margarita, Mikhail Afanasyevich would decide to play with his customary mode of transport in describing the “devilry” caused by Woland’s retinue: “An oak tree beside her was torn up by the roots, and the ground was covered with cracks all the way to the river. A huge slab of the bank, together with the pier and the restaurant, sagged into the river. The water boiled, shot up, and the entire excursion boat [river tramvaichik] with its perfectly unharmed passengers was washed on to the low bank opposite.” [4]

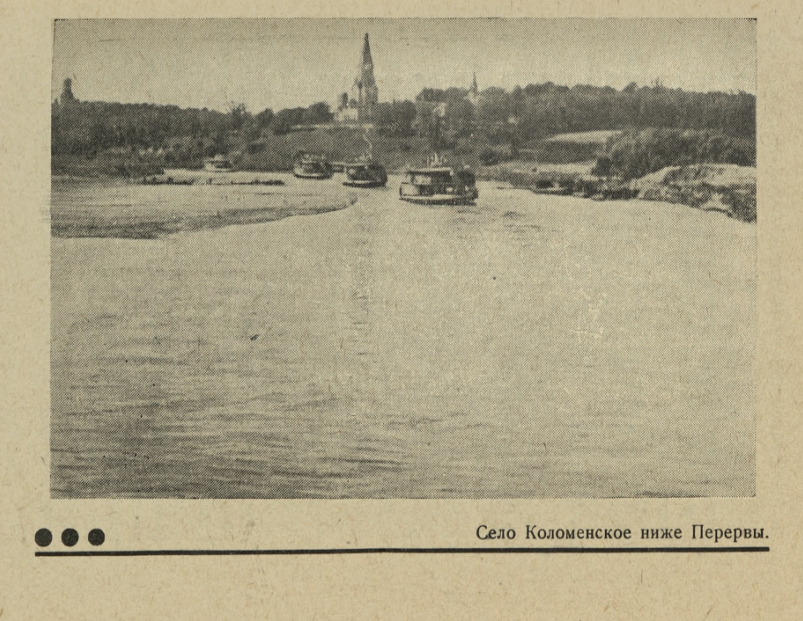

In a brochure issued by Narkomvod in 1937, Reference Book and Guidebook to the Moskva River within the City and in its Environs, the “starting point” for the movement of the river trams is marked as the Krylatskoye settlement, “picturesquely situated on the elevated right bank of the Moskva River—a place of dachas, good bathing, and beautiful beaches.” Then comes Kuntsevo, then Shelepikha, a dock at Krasna Presnya, and, afterwards, the pier at Kievsky Station.

“The most lively and interesting part of the Moskva River runs from Kievsky Station to Lenin Hills, passing by the Neskuchny Gardens and Gorky Park. From the river, an astounding panorama opens up onto the mountained right bank, covered in gardens and parks. In terms of beauty, this is the best part of the Moskva River” the guidebook goes on. [20]

All the same, at that time in the “proletarian capital” [this is how Moscow is referred to in the guidebook’s text—author’s remark], river trams were seen more as forms of leisure than of transport—boat rides were proposed to tourists arriving to Moscow by guidebooks as the optimal way of getting acquainted with the city’s landmarks. Notable among the listed attractions were “the Kremlin, the House on the Embankment, and the buildings of factories and plants.” [20:9]

Let us return to the Moskva River. From Kievsky station, river trams would run with stops past the Soyuzkino factory, the Potylikh street acid plant, Lenin (Sparrow) Hills, a certain Museum [it is possible that this was the Central Museum of Ethnology—author’s remark], Luzhniki, and, finally, the principal point, the city’s pride—Gorky Park. After disembarking passengers there, the river trams would run on to Balchug Island.

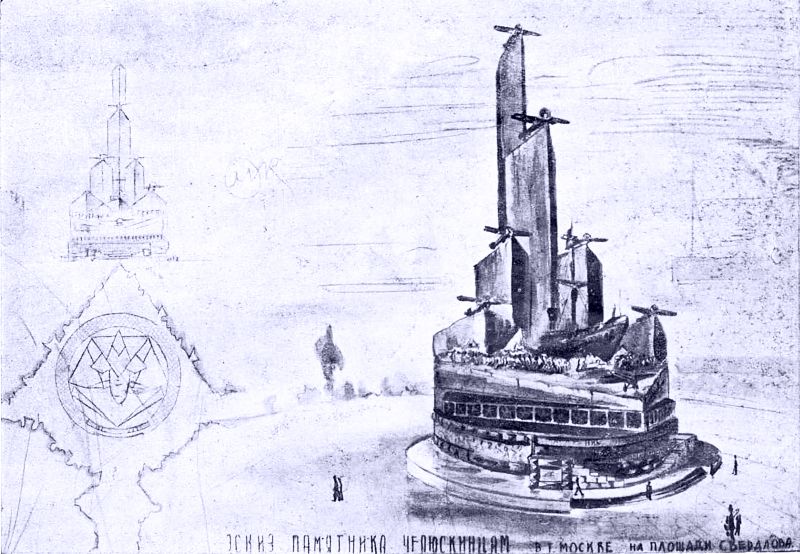

The guidebook also mentions that due to the construction of the Krymsky Bridge and the lining of the embankments, “there would be no movement of river trams” along the Vodootvodny Canal (right beside the GES-2 building) in 1937. Incidentally, in 1934, there had been plans to build a monument honouring the polar explorers of the Chelyuskin steamer on the spit near the canal where the monument to Peter the Great now stands. According to one of the proposals, a luminous lighthouse was to have crowned a fifty-metre column of marble, and the marble itself to have been encrusted with metal models of the airplanes that had saved the Chelyuskinites stranded in ice. The rescue of these sailors from the Arctic Ocean, the progress of which had been followed by people in the USSR through radio, was actively used by government propaganda. This story influenced river trams in many ways, as a number of boats were subsequently named in honour of the pilot-rescuers.

One of the river tram stops was the tragically well-known House on the Embankment (officially the House of Government). From the centre of the city, one could reach the out-of-town beaches by the river. Oleg Chernyshevsky, a schoolboy who kept a ciphered diary describing his everyday experiences and impressions in the 1930s, described his excursion on a river tram in August of 1937, a few months before his father was arrested and executed by shooting:

“We woke early, at 7am. At 8am, we went to the government house. There we boarded a river tram, to Lenin Hills. There, along with the rest of the excursion, we boarded two open boats and went upwards along the Moskva. We passed many bridges, three floodgates, the last of which was two-chambered, observed the Khimki river station, and arrived at Khlebnikovo village. There we had something to eat, played volleyball, bathed (I did not), and generally had a nice time. On the way back, we were soaked through by the rain, we did not go to the end and moored early. We changed to a tram and went by metro to the station.

Passing by the Red October Factory and the House on the Embankment, the river trams would stop by the pier beside what today is the Zaryadye Park: “Next, the water tram passes the construction of the Krasnokholmsky bridge. The next pier is Novospassky Bridge (left bank). Further, the river station of the Moscow-Oka River Shipping Company: steamships of the Moscow—Gorky and Moscow—Ufa transit lines depart from this station, and excursion steamboats begin their journeys from here.” [20]

All in all, in Soviet Moscow of the 1930s, there were, as there had been before the revolution, four key river transport routes. Particularly popular were rides on river trams from the AMO factory (today’s ZIL) to the Dorogomilovsky bridge (where Moscow-City stands today), and from Kamenny bridge by the Kremlin to Zaozerye, a village in the Ramensky district. [17]

Early river trams of the Stalin era could carry a maximum of around 140 passengers with two members of crew. This said, they were also working on boats with higher capacities of up to 250 passengers, almost as many as metro carriages. But such trams travelled principally along suburban lines.

Towards the beginning of the 1940s, it was decided to create new river boats for both inner city and suburban Moscow lines. But the war began. Some trams were converted into minesweepers and patrol boats, and on many of “these small boats, ammunition and reinforcements were transferred to the burning Stalingrad and the wounded taken out.” [17]

During the war years, one could only dream of river tram rides—or remember, as the twenty-three-year-old military translator Vladimir Stezhensky did:

“I remember our Moscow on spring evenings in May, our Park Kultury, Landyshevaya Lane, rosebushes in flower beds, music on concert stages, the smell of the Moskva River by the embankment, rides along the river tram past Sparrow Hills, the spreading crowns of trees leaning over the river. And my room, the open window, through which the noise of evening Moscow bursts in, and the smells of spring, fresh young leaves, the intoxicating smell of flowering bird cherry.” [15]

“Moskva” and “Moskvitch”

After the victory over Germany, Soviet rivers were filled with trophy vessels—“steam and diesel tugs and barges, self-propelled ships and boats—among these were a number of German river trams,” which would go on to be used in Soviet navigation for decades. [10]

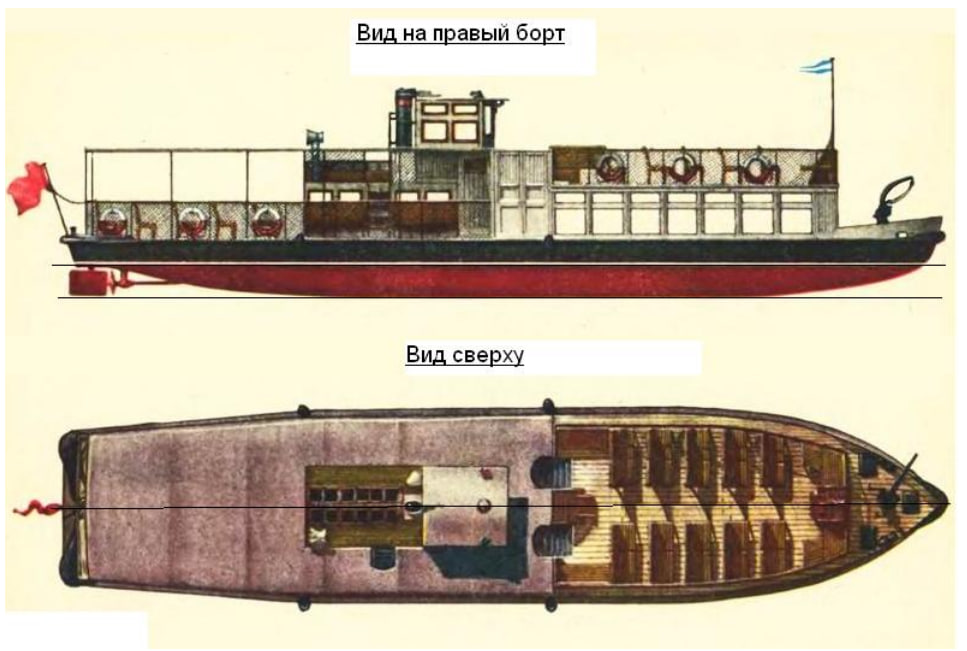

Demand for river transport grew, and the Ministry of the River Fleet of the RSFSR decided to build new water trams. In 1946, a project for a motorboat of a new type—the “544”—was worked through at the Central Technical-Construction bureau in Leningrad. A few years later, in 1948, the shipyard in Moscow began to build these trams en masse, which had received the reasonable name of “Moskvitch.” People rode these not just along the Moskva River, but also through “many waters… from the Gulf of Finland to Amur.” [11]

“Moskvitchs” continued to leave the shipyards until the mid-1970s, with a total of around 500 boats built. In order to differentiate one from another, they were marked with the letter ‘M’ and a serial number, without being given their own names. Each could carry around 150 passengers. Typically, a red star burned brightly on the bow or bridge of Soviet motorboats. In the case of the “Moskvitch,” this symbol was located on the “forehead”, where the bridge was located (however, in the next type—the “Moskva”—the serial number of the boat would occupy this place).

More and more, the new generation of Soviet river trams were tenderly termed “tramvaichiki.” This said, most often, the simple and habitual “tramvai” was used. The school teacher Leonid Lipkin recorded his impressions of a school trip with many children on a “tramvaichik” at the end of the 1950s:

“The second, third, fourth, and fifth classes took a ride along the Moskva River in river tramvaichiki M-21 and M-22 yesterday. I also went on this farewell ride with my class. […] The tramvaichiki were accompanied by flocks of seagulls. The journey was very nerve-wracking for teachers: one needed to be careful that no one fell overboard. The tramvaichik, sometimes driven by a man, sometimes driven by a woman, cut quickly through the dirty waters of the river, overtaking other boats. Each overtaking was accompanied by an enthusiastic roar from the guys.”

In June 1958, Lipkin described his short trip to Gorky Park—this route was particularly poplar with Muscovites: “In fifteen minutes, we were already riding in the small boat—the river tramvaichik—along the dirty Moskva River. We sat on the upper deck. To the right, a beautiful view opened onto Gorky Park: trees, bushes, grass, and little houses beyond the trees.”

In the 1950s, river trams continued to fulfil a public transport function, but they were increasingly used for leisure. During a trip to Moscow in the summer of 1954, the Perm worker Alexander Dmitriev recorded in his diary:

“In the morning I left for Gorky Park, walked around there. […] Afterwards I boarded a river tram and rode it down the Moskva River to the very last bridge. And then back again to Lenin Hills. There I came out onto the bank, bathed in the Moskva River, and, climbing up the hill, had a look at the new State University—the Palace of Science.” [5]

In the same year, the seventeen-year-old Oleg Amitrov remarked that river trams seemed to him rather more luxurious than usual transport:

“We walked over to board the boat. It exceeded all our expectations: you see on the way, looking at the river trams on the Moskva River, we were saying that such luxury was inaccessible to us, but it turned out we were riding a very comfortable river tram, with soft sofas and warm cabins.” [1]

In 1969, “Moskvitchs” began to be gradually replaced by new motorboats of the “Moskva” model. These two-decked trams, in contrast to their predecessors, had a closed passenger salon, as well as benches under an awning on the second deck. On some of them, the deck had a glass roof and walls. They can be seen to this day on the Moskva River.

In 1976 the bard Yuri Vizbor even wrote a song about the river tram “Moskva-12”:

Along the longest road of Moscow

Along the quietest road of Moscow

Where there are no leaves, but much blue,

There our tram glides along bridges.

“Moskva-12” is not a an icebreaker

But the Moskva is a rivulet, not a Neva,

And for me with you its so simple and easy

As though here it already isn’t Moscow

[…]

The end point. The granite pier.

We go out into life, leave this quiet paradise,

Ah! If only “Moskva-12,” ageing tram

Would rock us into old age!

From the beginning of the 1980s the role of the river trams in public transport declined—the metro, land trams, and trolleybuses were developing in Moscow. Nevertheless, right until the collapse of the Soviet Union, the capital's authorities preserved the river routes, even if they were subsidised.

“Relax, enjoy, and see”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, state-owned river tramvaichiki broke the papirossa smoothness of the Moskva out of habitual inertia. Most of the trams were bought by private carriers in the first ten years of the new government. Their design was the most diverse, and for many years new river boats ceased to be built in Russia, which was content with old Soviet models.

From the beginning of the 1990s, one finds almost no mentions of the river trams in diaries. Excepting Oleg Amitrov, who records in 1993 that “the tickets have become much more expensive.”

From the end of the 1990s, the motorboats of seventy shipping companies ran along the Moskva River, but they had no stable schedule, and began to specialise in banquets and parties. This continued until the end of the 2000s. The dozen or so sharp-nosed, greenhouse-like boats of God Nisanov and Zarakh Iliev’s Radisson flotilla have since the end of the 2010s intermingled with ridiculous, valenki-like “Sunflower” models, which the city authorities hoped to launch in time for the Football World Cup in 2018 as modes of transport, but which ended up passing into private hands; old “Moskvitch” and “Moskva” trams also crawl about. A number of them have undergone ruthless cosmetic repairs and lost their original silhouettes, while others have been painted and draped. Many of the old Soviet motor ships now simply rot and rustle along the banks of half-forgotten reservoirs.

City authorities have tried a number of times to revive the river tram as a regular mode of transport rather than as sightseeing fun. The Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin hoped that river transport between a number of areas in Moscow would be opened by 2020. But again, it didn’t work out—this time due to the outbreak of the fight against the coronavirus. The launch of the new transport network was postponed once again, to 2023. Precisely the hundred year anniversary of the launch of the first Soviet river trams in 1923.

New, extravagantly shaped river trams—something between accumulators and moving balconies—will be powered by electricity. For this, city authorities are constructing a “few dozen piers with electrical charging stations.” And they want navigation to run both in summer and in winter. Panoramic windows are among the features of the new models, but it seems there will no longer be large open decks.

“New ships of ice class should be launched by the beginning of the season […] I hope that this work will be completed and that Muscovites will get convenient routes that will save time, of course, and will, in fact, become new touristic routes”—said Sobyanin.

Notes:

[1] “Olenin-Volgar wrote many superb articles about the rivers of Russia. Today, these articles are lost and forgotten. He knew every whirlpool, rift, and log of dozens of rivers He made simple, unexpected plans to improve navigation on these rivers. In his free time, Olenin-Volgar translated Dante’s Divine Comedy into Russian.”

— K. G. Paustovsky, “Golden Rose,” in Collected Works in 6 Volumes, vol. 2 (Moscow: State Publishing House of Fiction, 1957), 487–699.

[2] “The Central Executive Committee of the USSR resolves: to erect a monument in Moscow in memory of the Chelyuskin polar campaign of 1933–1934, which took place in extremely difficult conditions on the ice of the Arctic Ocean, ending on February 13, 1934 with the destruction of the Chelyuskin steamer, which was crushed by ice, after which followed the courageous survival of participants of the campaign’s on ice floes for two months, then in the Schmidt Camp, of the heroism of their conduct and of the completion of the rescue of expedition members, scientific materials, and property, completed on April 13, 1934.”

—Moscow, Kremlin. April 20, 1934, published in Proceedings of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee 94, April 21, 1954.

Bibliography

[1] Amitrov, O. V. Circles of Communication. Moscow: Media-PRESS, 2013.

[2] Brontman, L. K. Diaries 1932-1947. Samizdat, 2004.

[3] Bulgakov, M. A. “Under heel.” Diary May 24, 1923—December 13, 1925.

[4] Bulgakov, M. A. The Master and Margherita, translated by Richard Peavar. London: Penguin, 2007.

[5] Dmitriev, A. I. Personal diaries 1941-2001. Perm State Archive of Socio-Political History.

[6] Bulgakova, E. S. Diary of Elena Bulgakova. Moscow: Book Chamber Publishing House, 1990.

[7] Diary of Oleg Chernevsky. “Prozhito” project. Accessed April 10, 2023, https://corpus.prozhito.org/person/808.

[8] Ilf, I., and Petrov. V. Moscow from Dawn to Dawn. Moscow: Goslitizdat, 1961.

[9] Nikolaev, A. S. Brief Historical Sketch of the Development of Water and Land Communications of Trade Ports in Russia. Saint Petersburg: MPS Printing House, 1900.

[10] Okorokov, A.V. “River trams (part 1),” in Journal of the Heritage Institute 1 (2015).

[11] Okorokov, A.V. “On the history of ‘river trams’ in Russia,” Historical Journal: Scientific Research 3, no. 15 (April 2013).

[12] Okunev, N. P. In the years of great upheavals: diary of a Moscow man in the street 1914–1924. Moscow: Kuchkovo Pole Publishing House, 2020.

[13] Paustovsky, K. G. “Golden Rose.” Collected Works in 6 Volumes. Moscow: State Publishing House of Fiction, 1957.

[14] Olening-Volgar, P. A. A Ride Along the Moskva River. Guidebook of the Moskvoretsky Passenger Shipping Company. Moscow: V.G. and V.A. Zhdanovich Printing House, 1910.

[15] Stezhensky, V. I. Soldier's diary: military pages. Moscow: Agraf, 2005.

[16] Fedenko. I. I. “Moscow–Ufa: A Guidebook to the the Moskva River, Oka, Volga, Kama and Belaya for navigation 1937,

[17] Shukhin, I. “River Tram.” Technology for the Youth 12 (1986).

[18] “River tram routes from Luzhniki to Spartak stadium will be launched for the 2018 World Cup,” 360tv, accessed April 20, 2023, https://360tv.ru/news/transport/marshruty-rechnyh-tramvaev-ot-luzhnikov-do-stadiona-spartak-zapustjat-k-chm2018-14325/.

[19] “Along the Moscow River: when new transport will appear in the capital,” mos.ru, accessed March 17, 2023, https://www.mos.ru/news/item/46231073/.

[20] Reference Book and Guidebook to the Moskva River within the City and in its Environs: Navigation of 1937. Moscow: Narkomvod, 1937.

sreda@v-a-c.org

All rights reserved. Reproducing or using the materials from this web-page without written consent of the rightsholder is forbidden.