Felix Sandalov

Dungeon Vapor

Judging by the silence of the world’s music media, no new genres emerged in 2019. As we take a look back at the music of the twenty-teens, we might note that phenomena as interesting to contemporary criticism as vaporwave and the new wave of dungeon synth did not exist, perhaps, in this period. If these terms do not mean anything to you, you can start with the brief introduction to the genealogy and the rationale of both genres. If you are familiar with them, you should immediately jump part to the critical portion of this article.

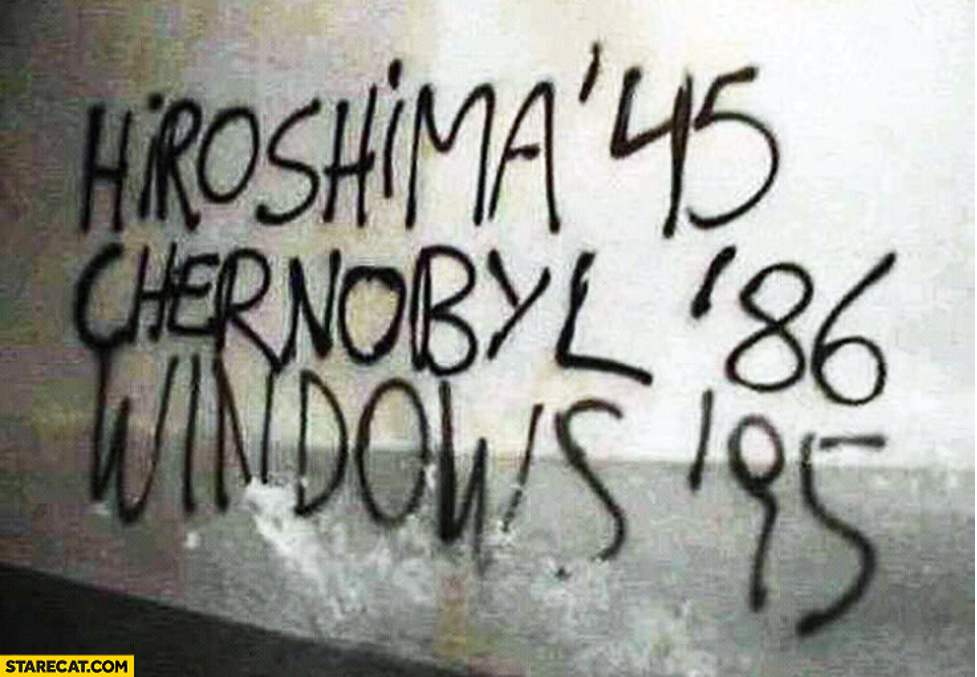

Many vaporwave artists have a message similar to the witty joke of this unknown graffiti artist: the list of the most high-profile manmade disasters of the twentieth century also includes the spread of personal computers.

VAPORWAVE

Introduction: Mallsoft as a Special Case

Here, a premium is placed on the very first, uncertain knocks of the digital age on the doors of everyday life: iridescent trills as ringtones instead of beeps, diffuse background music at the supermarket, the acoustic minimalism of Windows 98, soundtracks for fifth-generation video games—in short, the dust that has settled in the corners of the collective subconscious. Hence, the visuals: a neon fog, the flickering of countless screens, the naïve primitivism of three-dimensional modeling, archival views of Japanese megacities, katakana, and everything related to computing. According to vaporwave and its preachers, in the beginning was not the word, but the number, and the number was zero: while other types of time travel through music (chiptune, chillwave, hauntological pop) imply the aging of sound, then the symbol of vaporwave is the CD with its crystalline purity and infinite number of possible meanings.

—Felix Sandalov, “Vaporwave,” Afisha Daily (2013)

It is Franken-music, using various pieces of former wholes to create a new being.

—Grafton Tanner, Babbling Corpse: Vaporwave and the Commodification of Ghosts (2016)

Vaporwave is the specter of capitalism. Vaporwave is a digital utopia. Vaporwave is Situationist praxis in sound. Vaporwave is a mirror held up to the face of an android that is unaware of its mechanical essence. Vaporwave is the electronic scene’s. Vaporwave is a joke that has gone too far.

All these statements are true. My forecast turned out to be wrong: in 2013, in the first Russian-language article about the phenomenon, I wrote that the whole business would crash and burn in a year or two. Back then, there were a couple of hundred vaporwave albums. Today they are more than sixteen thousand and counting, and the genre keeps sprouting more and more new subgenres, for example, the recently crystallized mallsoft (aka mallwave), with which we shall begin this vivisection.

Mallsoft is a languid variety of vaporwave (which is also quite languid): a sparse series of sounds filling the space of an invisible atrium. Even songs by popular artists that are merely processed as if they were playing in an empty shopping center are considered mallwave. However, why even mention them? Filching samples and demonstratively rejecting copyright is not a matter of shame, but a matter of pride in the vaporwave family, and the kitschier the source, the better.[3]

Roughly speaking, mallsoft is just pleasant background music that attracts no attention, suggesting a parallel with Muzak, a revolutionary invention of the thirties, the authentic acoustic wallpaper for elevators and shopping centers that the British press dubbed “canned” music. Canned music was meant to encourage the consumption of canned food: how dehumanizing does that sound? Muzak served as a buffer between customers and the machinery of the rapidly multiplying department stores, a barrier designed to make the shopping experience barrier-free by muffling the sounds of refrigerators and loaders, the cursing of warehouse clerks and the creaking of carts and, ultimately, trying to push the mood of shoppers in the right direction. Of course, this functional approach was criticized from the left, and, indeed, with a little digging we can find a lot of disturbing episodes in the history of Muzak. For example, in 1934, at Muzak’s studio in New York, the National Fascist Militia Band, organized on Mussolini’s orders, recorded two and a half dozen songs—including the US national anthem and a ditty entitled “The March on Rome (Anthem for a Young Fascist)”—which were then played in hotel lobbies and stores under the more modest moniker of the Pan-American Brass Band. It would be another seventy-five years before Muzak was appropriated by (mostly) left-leaning vapor artists.

However, the mallsoft aesthetic was inspired not by the thirties, forties, and fifties, but by the late eighties, when shopping centers and mall culture reached their apogee. The metaphor of “shopping centers as the new churches” is a hackneyed one, but it did not seem so outdated at the time (like shopping centers themselves, which ironically are now often turned into churches in the literal sense). Like a huge amount of other music, mallsoft evokes an imaginary space, only in its case this space is not an organ hall, stadium or smoky train carriage, but the sterile atmosphere of the shopping center, a non-place where people do not live, but move around: safe, always the same structurally, and, simultaneously, always pleasing us with something new.[4]

This brief nostalgia for the world of thirty years ago has several possible explanations. First of all, it was a time when a lot of things were made—toys, cartoons, video games—that proponents of the genre encountered in their childhood. It also represents a longing for the Indian summer of capitalism: the triumph of WASP ethics, the blue-eyed American dream, the clear prospects of progressive neoliberalism. “The most beautiful thing in Tokyo is McDonald’s” is also true in the case of mallsoft, because the shopping center is a universal space in which, regardless of where it is on the map, you can find the same multinational brands, the same principles of spatial organization, the same music—the same Muzak. Mallsoft’s crucial function is to introduce a bit of anxiety into this imaginary space through defamiliarization, by disturbing the all-consuming comfort with static and glitches, by reminding us that all this is nothing more than a passing fad. Mallsoft does not guide us through the noisy, carefree, weekend shopping centers of the past, but through their abandoned, incorruptible ruins. Who killed the malls? The internet did.

Vaporwave is the principal genre of the internet age, its headstrong bastard. Vaporwave is both Muzak, a metacommentary on it, and an eraser that blurs the line between music and Muzak. In part, this is what Simon Reynolds has dubbed “conceptronica”: music that can thrive equally well in clubs and museums. Only in the case of vaporwave, its main habitat is still the net.

Vapor is something ephemeral and elusive. Vaporware (by analogy with software and hardware) is a term for gadgets, programs, and games—in general, for something hi-tech—that has never seen the light of day and, perhaps, should never have seen it at all. It was a common trick in the eighties, an act of pure industrial disinformation: many companies, including Microsoft and Nintendo, announced the imminent release of a revolutionary product in order to drive their competitors into a technological dead end. Even at the level of its name, vaporwave appeals to unreality, to disappointed hopes, to an alternative history.

Not all vaporwave artists see their work as a critique of capitalism or espouse Marxist attitudes. However, as noted by Nowak and Whelan, “In terms of situating vaporwave within a broader discussion about capitalist aesthetics, one of the important features of the genre is that […] it is […] consistently discussed as a means or attempt to make capitalism, consumerism, and the homogeneity of corporate culture knowable, audible, and ‘feel-able’ as objects of expressive critique.”[5] Thus, the “vaporwave and capitalism” line has been and remains dominant in the vast majority of articles and posts on the topic, which allows us to close our eyes to the heterogeneity of the stances on the issue taken by many musicians. We can draw a parallel: members of Russian bands that perform Oi!—a variety of punk rock associated with representing the working class—often have nothing to do with the working class, nor do their listeners. This, however, does not change the generic frame.

At the same time, the similarity of the genre’s methods to the tools of Situationism is visible to the naked eye. Vaporwave musician Robin Burnett, known by the pseudonym Internet Club, for example, explicitly stated in an interview that he wanted to do something “Debord-like” by means of defamiliarization. The godfather of the genre, Daniel Lopatin, cites Gilles Deleuze, Julia Kristeva, and Manuel DeLanda as sources of inspiration, while Ramona Xavier, vaporwave’s godmother, was sympathetic to accelerationism, which can also be seen as a form of radical criticism of the status quo. This is not to mention the beacons scattered in the titles of recordings by various artists, such as “I Consume Therefore I Am,” by mallsoft pioneer シ シ Corp, or the Geo Metro album that could be purchased on physical media: it was loaded on a burner. Burners are disposable phones, popular among those who want to avoid having their conversations surveilled. It was an elegant nod to two industries of death at once: the military and drug dealers.

Three Essential Early Vaporwave Albums

Chuck Person’s Eccojams Vol. 1 (2010)

Chuck Person’s Eccojams Vol. 1 is considered the first vaporwave album. Chuck Person is not a real person, of course, nor did he have any plans for a second album. The album was recorded by Daniel Lopatin, who is renowned for his witty ideas. The cover and the word “ecco” itself are references to the eponymous popular 1992 video game about a dolphin saving the planet.[6]

Prior to this, Lopatin’s work was characterized as chillwave (i.e., music for relaxation) or hypnagogic pop—from the word hypnagogia, a state between sleep and reality, a light trance, which such music tries to induce. How? By inserting into the musical flow background quotations of cult video games and movies, by a subtle appeal to the body of collective nostalgia, moreover, a nostalgia that is quite selfless and kind, tinted only in warm shades.

In 2009, everything broke down: an economic crisis erupted that, according to the author of the book Crashed, Adam Tooze, continues to this day, but in the form of setbacks for democracy everywhere and the rise of far-right sentiment. It was against this backdrop—the profound failure of forecasts for the growth of universal prosperity—that Chuck Person appeared like a canary in the coal mine. Optimistic models of the world economy, championed, among others, by Nobel Prize winners, were proved wrong—and tens of thousands of people lost their homes in America, hundreds of thousands lost their jobs. The future had once again ceased to be so cloudless. Lopatin responded with an album suffused with anxiety and worry, hidden beneath innocent melodies and samples from pop songs and video games. On paper, he had seemingly employed the typical box of chillwave tools, but in the case of Eccojams, he made a point of pointing out how illogically the samples are mixed, how they jam and break. In contrast to chillwave, this is a an awfully uncomfortable record—pure unheimlich.

James Ferraro — Far Side Virtual (2011)

The second key album of vaporwave is Far Side Virtual by James Ferraro. In terms of visual aesthetics, it is anything but canonical. The vaporwave canon, which gelled later, still insists that sources (both for samples and the design of releases) should date back to the period between the 1970s and the 1990s (up to and including 2001—you can guess why). However, the album is one of the standards of the genre, largely because Ferraro was able to recreate sonically the feeling of a sudden breakdown in reality, one very different from what was described by science fiction in the middle of the last century, and hilariously similar to it at the same time. It is worth quoting Ferraro himself: “If you really want to understand ‘Far Side,’ first off listen to [Claude] Debussy, and secondly, go into a frozen yogurt shop. Afterwards, go into an Apple store and just fool around, hang out in there. Afterwards, go to Starbucks and get a gift card. They have a book there on the history of Starbucks—buy this book and go home. If you do all these things you’ll understand what ‘Far Side Virtual’ is—because people kind of live in it already.”

An overheated consumer society that has descended into endless self-repetition is the central theme of Far Side Virtual. In fact, it is one of the fundamental principles of early vaporwave: the generous appropriation of other people’s music, distorted and deconstructed. Slowed down three times, any smash hit reveals its inhuman nature. If it is looped and smeared thinly, making it the background for an otherworldly motif, its inhumanity will manifest itself in all its glory. This deliberate jamming—a glitch doomed to mechanical repetition, claiming to be the remnants of the “soul”—is one of the most impeccable examples of musical meditation on the current culture. In 1999, the big Hollywood studios released half a dozen sequels; in 2019, the schedule of film premieres included thirty sequels and reboots. Vaporwave perfectly expresses the feeling, which had built up by the twenty-tens, that the culture has reached the stage where, completely self-contained, it consumes and regurgitates itself.

The world is ruled by ultrashort-term nostalgia. We have witnessed the triumphant return of smartphones and video games that first saw the light of day a decade ago, and grunge has been revived, but mainly as a fashion for certain clothes. Half-forgotten franchises make comebacks, adapted to the new-model ethics and morals. Micro-cults of the past are carefully put back on their feet by armies of marketers.

It all adds up to a rather tedious picture, about which there is nothing new. Permit me to quote myself again: “Vaporwave is not a longing for the old, but for the absence of the new.” Ferraro cemented this feeling in the most graphic way. The only downer was that he never released Far Side Virtual as a compilation of polyphonic ringtones, as he had planned.

Macintosh Plus — Floral Shoppe (2011)

The third album that played an outsized role in the genre’s evolution is the album Floral Shoppe by Ramona Xavier, who has recorded under many aliases. (Her return to the Macintosh Plus alias was announced in 2020, so it is likely that, by the time this article is published, her new album will have been released, becoming a weighty postscript to the genre’s history.)[7] Actually, it was this record that paved the reinforced-concrete channel of the vaporwave aesthetic, which (it is time to reveal this simple secret) primarily consists of a set of methods and techniques. While we have discussed the said musical techniques above (although in this respect as well, Floral Shoppe has credibility in spades: what could be blunter than the wails of a dehumanized Diana Ross,[8] multiplied by the standard beeps of unknown programs?), the visual tool bag critical to the integrity of vaporwave as a genre, can be divined by contemplating the album’s cover.

The Visual Basics of Vaporwave

This seemingly naïve collage has been the basis for countless memes, covers of other people’s albums, and music videos, and it will eventually go down as one of the images that defined the decade. What are its parts?

– Colors. The fusion of unnatural shades of pink and blue can be attributed to the aesthetic code of Tumblr, where images of acidic neon colors were popular at the time. For vaporwave, the palette (the palette of the unreal, impossible to find in nature and even pre-computer-era art) would become an entry permit to the genre.

– A mix of katakana and the Latin alphabet. On the one hand, the Babylonian babble is an allusion to cyberpunk, with its transnational corporations, erasing the distinction between east and west; on the other, it is an obvious nod to the witch house scene, where artists write the names of their projects in such a way that they are as difficult to read as they are to find on internet: it is a cute attempt to add a little esotericism to the all-access age. Nor is the choice of Japan by vaporwavers as the source of an endless number of music and visual samples random. Modern Japan is the land of petrified progress. Where else can you find people still using fax machines, buying CDs, and playing video arcade games every day?

– VHS. Inherited from chillwave and alluding to the imagery of the eighties (as muddy as our memories), this technique is emphatically disturbing in the case of Floral Shoppe: clouds are gathering over Manhattan, where the Twin Towers still stand. The source of the freeze frame is an exorbitantly psychedelic Japanese advertisement for Fuji videotapes.

– The end of history. Speaking of the Twin Towers, many vaporwavers obsess over the events of September 11, 2001. As musician シ シ シ Corp, who dedicated an entire album (News at 11) to the tragedy, said, “When the Twin Towers were hit on that day in September the old world died. It’s like the whole planet suddenly opened up and changed, [and] not for the better. Gone were the peaceful days.” For many who took on faith the optimism of Francis Fukuyama, the man who proclaimed the victory of democracy and the “end of history,” it was a hard lesson that conflicts inevitably follow other conflicts. In an interview, 猫 シ Corp noted, “One thing I found out when browsing samples was that when a news station couldn’t deliver the live image right away, they cut to McDonald’s commercials.”

Another thing binding the vaporwave scenes around the world together is the cultural hegemony of the United States in the 1980s and 1990s. Georgy Oblapenko, who edits the vaporwave Telegram channel 美学はどうか, notes this factor: “Although the genre originated in the United States, it seems to me that if these images were not universal for a huge number of countries around the world, vaporwave would have remained a very local thing. That is, going completely against common ideas and aesthetics, and building a [local] identity would probably not work, or the result would no longer be vaporwave.”[9]

– Kalokagathia. In the foreground we see the head of Helios, the sun god, as beautiful as the sun itself. It is an allusion to kalokagathia, a Greek concept that literally translates as “beautiful virtuosity.” An important concept in Greek aesthetics and ethics, kalokagathia posits that someone who is beautiful on the inside is also beautiful on the outside, as illustrated by ancient sculpture. It is an easy leap from the ancient idea of virtuous beauty to the era of neoliberal frenzy (thoroughly evoked on Floral Shoppe), with its cult of the healthy body, fitness, aerobics, bodybuilders, sexy Hollywood movie characters, and so on. Plus, as Alican Koc from the University of Toronto notes, it can be seen as an ironic nod to an era when the word aesthetics had a completely different meaning.

– 3D surrealism. The checkered floor is a hallmark of countless images, from Escher’s prints to Twin Peaks, and its obsessiveness is disturbing and discomfiting. It also suggests the world of digital rendering, an empty demarcated space you can place any object or context— the very dissecting table where an umbrella and a sewing machine could meet. In this sense, the gaze that sees the cover of Floral Shoppe is not the gaze of a person, but of a disembodied demiurge soaring over a world that it has constructed from the shards of different eras. It is a manifestation of the virtuality of Macintosh Plus’s world—and an appeal to massurealism.

– Illusion. The rectangular structure in the upper-right corner is familiar to everyone who studied English in Russia in the 1990s: it was on the cover Vereshchagin’s ubiquitous English textbooks. Mathematician Roman Mikhailov argues that the background of the pyramid stands for knowledge per se, gnosis, while the visible cubes represent the knowledge available to the individual. But those who have spent several years of their lives with Vereshchagin’s textbooks know that, with a certain amount of practice, you can visually change the spatial orientation of the cubes—a subtle hint at the ephemeral nature of knowledge as such.

— Plus some more indecipherable symbols, references, and false interpretations.

Sources of Anxiety

The irritation caused by the emphatically clumsy plastic sound of many new vaporwave releases is not so dissimilar to the anxiety evoked by the genre’s early masters. In subsequent years, the ideological message was replaced with an aesthetic, the scene was commercialized considerably, and vaporwave’s mainstream has come, structurally, to resemble witch house, only instead of acid Gothic, we see an emasculated retrofuturism. What, then, is the source of this anxiety?

1. The Absence of Long-Term Plans

In the autumn of 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued a report that made headlines around the world: Global Warming of 1.5 º C warned that we had twelve years before reaching the point of no return. If the planet warmed by more than one and a half degrees (which in itself would results in drastic changes for most people), hundreds of millions of human lives and tens of trillions of dollars would be at risk. The retro-futuristic tone of vaporwave, stuck forever in the radiant eighties, appears to be an escape from reality, chilling the soul more than any disaster film. Add to this the growing gap between the richest and the poorest, the emergence of super viruses, perpetual political conflicts, and the threat of nuclear weapons and, as the father of cyberpunk William Gibson wrote on Twitter, “In the 1920s, the phrase ‘the 21st century’ was everywhere, but how often do we see suggestions for ‘the 22nd century’ nowadays?” Such retrofuturism is born when it is impossible to imagine the future, or when we are unwilling to imagine it.

2. The Loss of Confidence in Technology

Aside from the people who deny the consequences of anthropogenic overload, restrained optimism about the future is experienced only by the solutionists—that is, people who believe that technology can solve all the problems that humanity already faces and all the problems that are still only parked down the street, as it were. It is curious that the heralds of solutionism do not hide (see the upcoming book by Jacques Peretti with the telling title Apocatunity) that, despite everything, one can also make good money on the upcoming challenges: read what Elon Musk and Peter Thiel have said on the subject. People are also generally fed up with rhetoric about the benefits of “disruptive technologies”—with the idea that the internet, social media, etc., radically transform our lives and minds for the better, democratize societies, and liberate us from borders and wars. Amid the dizzying escalation of surveillance over everyone who has access to the net, nervous laughter is the only way to respond to such talk. Again, the exploitation of the Web 1.0 style by many vaporwave artists can be interpreted as the desire to return to the immaculate phase of the internet’s evolution—to rosy dreams of a digital revolution without the later emergence of concentration camps. (If you grimaced when you read that, have a gander at this news. Even if it is a blatant exaggeration, China’s claims leave most of the dystopian works of the twentieth century in the dirt.)

3. Desubjectification

The conspicuous forfeiture of subjectivity in vaporwave (as evinced, among other things, by the anonymity of the music’s producers and their extremely rare concerts)[10] can be compared to the overall desubjectification of the digital age. Everyone nowadays can be reduced to a set of data collected from the countless digital footprints they leave behind every day. Popular-scientific literature of all sorts bombards us with revelations that our actions and opinions are predetermined by genes, hormones, the evolution of the nervous system, language, geography, and room temperature. Add to this list political apathy and changes in the way we talk about our feelings (after all, when we are “triggered,” we are in a passive position vis-à-vis external stimuli), as well as the above-mentioned premonition of a global catastrophe that we cannot affect.

4. Transhumanism Without

It is not so much a political fear as an ontological one—the premonition that the loss of subjectivity will be followed by dehumanization on a planetary scale; that, at best, there will be a transition to a new form of existence, guided by “smart AI.” This feeling is fueled by machine-gun bursts of news that neural networks have jumped another hurdle in areas that were considered exclusively “human”—for example, creativity. (Of course, like any uncomplicated music, vaporwave also boasts its share of robocomposers.) Another of the genre’s tension lines leading to Japan is the anime aesthetic, and it is hardly worth writing about the fact that the theme of posthuman existence is one of the main ones in anime (e.g., Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Ghost in the Shell, etc.). Also pay attention to how often real (non-illustrated) people appear on the covers of vaporwave albums, especially the people who make them. The correct answer is: almost never.

Some critics—in particular, Adam Harper, whose articles have had a huge impact on the genre’s reception—have argued that vaporwave’s hidden desire is not to return to the past, but, on the contrary, to accelerate capitalism; hence, accelerationism, whose main proponent is Nick Land, considered to be the father of the neo-reactionary movement. Harper writes, “Accelerationism is the notion that the dissolution of civilization wrought by capitalism should not and cannot be resisted, but rather must be pushed faster and farther towards the insanity and anarchically fluid violence that is its ultimate conclusion, either because this is liberating, because it causes a revolution, or because destruction is the only logical answer.” If this is true, vaporwave is the soundtrack of our world’s collapse, not only highlighting but also reinforcing late capitalism’s paradoxes.

5. Posthumanism Within

Another disturbing discovery, which is intertwined with psychedelics, neural networks, and centuries-old know-how for observing human behavior and consciousness, is that our brain can also be interpreted as a kind of machine, with all the glitches and static inherent in a complex device. We automatically recognize eyes when we see an oval and two dots, see a person instead of a stump covered with leaves, and hear screams when a door creaks; in fact, the sonic aspect of this is also audible in vaporwave, with its craving for endless illusion. At its best, vaporwave is music that has owned up to the nature of musicality—in particular, it is aware of the hook as a means of penetrating someone else’s mind. Tanner affirms the eerie nature of this discovery, quoting Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis’s book On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind: “the idea that thoughts are not our own, spontaneous, soul-engendered entities, but rather products of some invisible, subconscious script.”[11]

Another aspect that should be noted in this conversation about vaporwave, and which has not been raised by the genre’s theorists, is that the long process of dehumanizing music has come to its end in vaporwave. If popular music up to the eighties was somehow connected with names, vocal mannerisms, instrumental styles, as well as with the catchphrases, costumes, and lifestyles of the scene’s idols, then with the advent of shoegaze, the situation began to change. Magnetic front men have been replaced by “slaves of the lamp”—in this case, tube (and other) amplifiers that produce kilowatts of overloaded sound, which are the central subject of shoegaze’s message. In electronic music, the situation has evolved in a similar way, but even there the instruments are often more important than those behind them: Roland drum machines, Akai samplers, Yamaha and Roland synthesizers, each with their own recognizable sounds and patterns, rise like pillars from the sea of unknown producers. In the noughties, digital audio workstations (DAW)—electronic devices or application software used for recording, editing and producing audio files—reached the stage at which even novices could compose works by emulating the sound of any musical instrument that have ever existed, or by creating their own instrument.

Having lost the need to use analogue recording, organize space, and plug in and play instruments, the electronic music of the twenty-tens arrived at a level of abstraction in which everyone could sound unique and the same at the same time. The crystal-clear sound of classic vaporwave is an indication that music now generates itself—with almost no human involvement, or without what makes humans human.

Vaporwave’s In- and Out-of-Body Escapades

Soon after its introduction, vaporwave became a meme, which is not so much a joke as a virus that can spread in internet culture until it is no longer relevant to anything. A characteristic feature of memes is the removal of images from their context: you don’t need to watch the Russian cartoon Moonzy and His Friends to laugh at a meme about Wupsen; you can avoid reading Nietzsche or Kafka while delving into quasi-literary parodies; you don’t need to know anything about old video games to get the joke. Thus, judging by the demographics of its listeners, vaporwave also works for those who were not around during the time of Lycra, perms, and home shopping. Like other memes, vaporwave multiplies by repeating itself and producing hybrids, that is, by introducing elements of other musical constructions and symbolic systems (if these words are applicable to the wobbly parodies that make up the lion’s share of all the ingredients thrown into the post-vaporwave pot).

In the first case, vaporwave has been productively crossed with trap (vaportrap), hip-hop (vapor hop, which sometimes difficult to distinguish from cloud rap), gabber and noise (hardvapor), disco and house (future funk), ambient (mallsoft), and even such very difficult to explain microgenres as slashwave (which is vaporwave with a lot of sound effects including chorus effects).

The second route has even more twists and turns, leading us to Stalinist and Maoist vaporwave (laborwave), to vaporwave from the Russian nineties and Slavic criminal hardvapor, to Simpsonwave and climatewave (which riffs on TV weather forecast opening sequences), to Trumpwave (which extolls neoliberalism’s golden calf) and fashwave (which caused a stir in the foreign press) and even further, to “prehistoric” vaporwave. Don’t forget that vaporwave is a product of a time when a broad conversation about the very concept of offline can only be a travesty because we are always online. It is product of a time when plane crashes, school shootings, and extremist organizations instantly become memes, and medialization has reached unprecedented proportions.

DUNGEON SYNTH

Dungeon synth is a deliberately naïve variety of fantasy electronica, wickedly mixed with European folklore and featuring a raw basement sound.[12] The founder of the Falanster bookstore in Moscow, Boris Kupriyanov, likes to tell a story about an acquaintance who, after reading The Lord of the Rings, immediately set out in search of Middle Earth: “It’s written so well that it has to be true.” This apocryphal tale is a good basis for understanding dungeon synth’s popularity.

To imagine the genre’s musical foundations, it is enough to recall the music from the computer role-playing games and fantasy films of the eighties. Or you can turn to the intros to black metal albums, straddling the razor’s edge between solemn and sinister. Dungeon synth can basically be imagined as black metal on a diet: in keeping with the zeitgeist, the darkness is sugar coated and homeopathically dosed. The listener is not overwhelmed by a cannonade of blast beats and eardrum-piercing vocals, while remaining in the usual (gloomy and heroic) symbolic space. Figuratively speaking, dungeon synth turns the listener into a hobbit going on an incredible adventure. We are again faced with a form of escapism, but one radically different from the mode of escape offered by vaporwave.

But first we should discuss the similarities. Like vaporwave, dungeon synth is usually produced anonymously, and its main stage nowadays is the internet. Concerts are rare and usually comical due to the miserly means employed in the making of this music and the static figure of the artist at a laptop, at best surrounded by reenactors engaged in a sword fight.[13] Both scenes are marked by a high ratio of musicians to listeners and the close communication among them. This makes them resemble hobby clubs, thus helping them avoid the usual relationship between the artist releasing his music and his hungry flock They are united by the instrumental focus of the music (a low entry threshold that attracts amateurs) and the desolation of album covers, which in the case of dungeon synth, are chockablock with medieval castles, sacred groves, dungeons and dragons, all, of course, illuminated by moonlight or torchlight.

The genre originated in the early nineties,[14] primarily in the work of the Norwegian artist Håvard Ellefsen, who performs as a goblin-like creature named Mortiis. However, in an interview with Decibel magazine, Ellefsen reported that he did not even know that an entire scene had sprung up, inspired by his demo recordings. Interestingly, the emergence of dungeon synth as a global socio-cultural phenomenon[15] has taken place in the era of YouTube and Bandcamp: over the past ten years, according to Discogs, the genre has generated almost five thousand records, twenty-five times more than in the nineties.

I first encountered the genre in 2000, when I was given a single entitled “Icy Wasteland” by the artist who recorded it. He didn’t know the term “dungeon synth,” or, at least he didn’t use it in conversation, and the music he was making then passed as ambient. In the nineties, this music was not exchanged publicly: musicians traded tapes among themselves, and there were no specialized fanzines. In most cases, this music was completely obscured and absorbed by black metal. Only with the advent of broadband internet were the bottomless archives of homemade dungeon synth recordings flung open. “Icy Wasteland” can be retroactively labeled early Russian winter dungeon synth. Yes, that is a real subgenre.

Three Essential Early Dungeon Synth Albums

Mortiis — Født til å herske (1994)

In 1992, Mortiis quit the well-known black metal band Emperor to focus on what he called dark dungeon music: later, these homespun recordings would form the basis of the dungeon synth canon. On Født til å herske, we can hear all the qualities typical of genre: the primacy of atmosphere and “history” over variety, the ascetic sound and minimalist arrangements, and, most importantly, a sincere belief in yourself and what you do. Like the myriad subsequent dungeon synth recordings, Mortiis’s music is based on an implicit compact between artist and listener (in fact, exactly the same pact exists between fantasy writers and their flock): the belief that magic is as real as electricity, other worlds are hidden behind the veil of everyday life, and goblins can play synthesizers.

Depressive Silence — II (1996)

Produced by a semi-anonymous duo from the German town of Breisach, Depressive Silence II is a recognized masterpiece of the genre: it was one of the first attempts to approach dungeon synth not as a chilling tale from the crypt, but as a full-fledged receptacle for the fairy tale. It offers the listener a coherent drama that is not devoid of uplift (and, consequently, it sometimes verges on vulgar sentimentalism, but the vast majority of dungeon synth releases suffer from the same defect) and nostalgic day trips to the fantasy epic soundtracks of the eighties. However, these are not vaporwavish nods to childhood experiences, but pure escapism pushed to the hilt. Most reviews of the album by listeners reference the “journey” they went on: it is an effect that dungeon synth artists from all over the world would try to reproduce with varying degrees of success.

Burzum — Hliðskjálf (1999)

The album is worth mentioning, if only because of the enormous upset it causes to this day among listeners. For fans of black metal, who share the artist’s extreme nihilist views, there are too few familiar instruments on the album. In other words, there are none at all: the only thing that Varg Vikernes had at hand was a MIDI synthesizer of dubious quality and a recording device. For everyone else, this album is an embarrassment because Vikernes recorded it in prison, where he was doing time for murder and torching three churches. (Vikernes has never renounced his views: he has continued to popularize them on a video blog and Twitter since his release from prison in 2009.) But there is one little thing that keeps us from throwing Hliðskjálf on the same shelf with curious outsider records tainted by extravagant extremism—namely, the beauty and brevity of each track on the album, from the dark techno pulsations of “Ansuzgardaraiwô” to the airy, translucent “Frijôs Goldene Tränen.” Nor can the album be written off as naïve art, which is a term better applied to Burzum’s previous prison recording, which resembles the soundtrack to a third-rate Nintendo game. Vikernes has mentioned that one of the most important records of his youth was the darkwave classic Within the Realm of a Dying Sun by Dead Can Dance. Its influence can certainly be traced to Hliðskjálf, which generates a hermetic musical universe for telling the story the death of the gods and communicating the experiences of a person who would spend the next ten years in prison.

Mutations of Dungeon Synth

Like vaporwave, dungeon synth has reproduced by budding in a specific way, by adapting to the insignificant nuances of alien intonations, images, and mythology, by forming niche micro-scenes, including medieval (paradoxically, assigned its own league by network scribes), dark/depressive, epic, pagan, the previously mentioned winter, Slavic, forest, sea synth, children’s, and even Christmas. There is also a place for memetism, in which the originality of the formal experiment sometimes trumps the consistency of the musical utterance, and result is more of a one-trick pony than a template for other artists: Egyptian dungeon synth, samurai, pirate, Frank Herbert, dino, goblin, and so on. There are also the intergeneric hybrids with noise, ambient, 8-bit, hip-hop, and nicecore. When dungeon synth is crossed with dance music, it is sometimes labeled unholy dungeon synth, hinting at the sacrilegious presence of a hard beat in the usually spacious and deep fog of sound. The question arises: is there a crossover between dungeon synth and vaporwave? Of course there is.

Still, there are crucial differences between the two genres. While vaporwave is based on the great American myth, and is much more popular in the US, dungeon synth draws inspiration from Eurocentric fantasy literature and the corresponding folklore, and the lion’s share of its adepts hails from European countries. In contrast to vaporwave’s appeal to the recent past, paralyzed with an accelerating society’s techno sweat on its brow, dungeon synth can boast no less far-fetched roots: paganism, Viking morality, witchcraft, esotericism, and nostalgia for a world in which there was not a single piece of plastic.[16]

While vaporwave is often ironic, dungeon synth is often typified by deadly seriousness: for example, the Russian artist Morketsvind once ended a performance by saying, “Thank you to everyone who hearkened to my call.” Another feature of dungeon synth is the narrative bent of the tracks: the ability of artists to “tell stories” in sound and paint pictures of ambushes, scouting parties, epic battles, retreats, and victories is at a premium. And while vaporwave works with space, it is more appropriate to use the word landscape when talking about dungeon synth. The canonical image of the vaporwave artist is a nameless cosmopolitan lost in the mirrors of virtual reality, while the self-respecting dungeon synther is an RPG game master, entrenched in his moat-encircled world, who is not supposed to have a name, since names are signs of fictional characters.

The easiest way to arrange these phenomena on different sides of the musical ring is to employ the most banal recension of the postmodern and metamodern conceptual framework. Vaporwave is based on citationism, exploitation of pop culture, irony, on tearing the veil from the ordinary and de-automatizing it, on emphatic “soullessness” and identity erasure. Dungeon synth is typified by deliberate naivety, romanticism, mysticism, an emphasis on original musical material, claims to sacred knowledge, and the construction of alternative identities (e.g., hobbits, dwarves, goblins, Sumerians, etc.).

On soil richly fertilized by role-playing games, such identities easily take root: according to the 2002 Russian census, there were two hundred elves in the Perm region alone. Given the new logic of identity politics, in which everyone is free to choose their gender, beliefs, and religion, we could recall the menu for generating characters in role-playing games. But there is one important exception: in the modern world, we cannot choose our own class. It can be changed only through economic advancement or political struggle.

The origins of black metal and dungeon synth’s overall vector may suggest that, ideologically, it should be far to right of vaporwave.[17] I could not find overtly political statements by members of the scene.[18] (And, in the rare cases of flagrant “ultra-right dungeon synth” I did find, the inhabitants of imageboards had the same green ears as in fashwave.) Nevertheless, it would be difficult to dispute the conservative spirit of the scene, which is wrapped up in animism, worship of wise ancestors, and the mythopoetics of the German Romantics. The fantasy genre itself, although it seems comical to think such a thought, is now increasingly seen as a mouthpiece for right-wing sentiments. There has been increasing scrutiny of the views of genre’s founding fathers: for example, Robert E. Howard, who invented Conan the Barbarian, was known among other things for his racist tirades. The genre has also been aligned with a general sensibility that promotes the preservation of feudal borders between classes and continuous racial war, coupled with a mystical ecofascism à la the Nazi “blood and soil” ideologist Richard Walther Darré, who believed that every nation should live on its own land for “sacred” reasons.

Role-playing games have also been increasingly subjected to similar criticisms. Nor is it just a matter of Myfarog, the tabletop game invented by Varg Vikernes. (In particular, the Tolkien-inspired musician and permaculture enthusiast has argued that the word “elf” comes from the Old Norse albar, meaning “white,” with all the attendant consequences.) We can also recall such notorious cases as the scot-free rape option in Total, or the game RaHoWa, whose title (an abbreviation for “racial holy war”) speaks for itself. Although it is not entirely fair to reduce the fantasy genre and RPG to a set of racial and gender prejudices (not to mention the fact that this critique uses the method of carpet bombing, leveling all creativity by white men and invariably revealing the desired defects), the arrows fired sometimes still hit their targets, revealing concerned communities in the process.[19]

Curious in this respect is the case of the venture capitalist and libertarian Peter Thiel, who owns four companies named after magical artifacts or places from The Lord of the Rings: a mind that divides the world into immortal elves and orcs, who deserve total destruction, can be not only infantile, but dangerous. For example, residents of New Zealand, where Peter Jackson once shot a film version of Tolkien’s trilogy, are extremely concerned about the purchase of local land by Thiel and his comrades, who are planning to survive the imminent environmental catastrophe there.

Of course, the zeal of nameless artists to compose fairy-tale music for the hobbit tavern is difficult to compare with the power madness of one of the planet’s richest men. However, there is no such thing as being apolitical, and the silence of dungeon artists is often a division of labor: in their parallel black metal enterprises, they tend to speak out on controversial topics without pulling punches and in the categorical manner typical of the scene. The following argument could serve as a common platform for dungeon synth: “The world is too modern, and we should cultivate a magical perception of it.” Complaints about the lack of “spirituality” and “depth” around them is a refrain in the rare and tiresomely monotonous interviews with practitioners of the genre. This dovetails with something written by Tolkien, who was one of the first to register the phenomenon of escapism in existential terms. In the essay “On Fairy-Stories,” he interpreted escapism as a conscious flight from the “rawness and ugliness of European modern life”—from machine guns, factories, and bombs—to the world of literary fantasy.[20]

In fact, back in the noughties, a radical ecological stance enabled black metal to save face and maintain its off-the-scale misanthropy, the genre’s cornerstone, while rejecting Nazi symbols and teenage Satanism, and making an ontological turn toward the subjectivity of the inanimate.[21] It is possible that a similar move could bring dungeon synth to a new level, because in addition to appealing to childhood experiences of reading fantasy epics, it is the shards of black metal lodged in the body of the genre that make it unique and attractive in the eyes of the growing internet audience. Otherwise, it would be (generally speaking: we are not talking about the rare artists who release recordings of truly breathtaking beauty) a primitive and naïve variety of electronica for the most stubborn retrogrades and fans of audio memes. As for the musical side of things, it seems that the genre has become a prison of thought, and a return to the roots could be beneficial. There is still a lot of stuff to rethink carefully: from Mortiis’s Pet Shop Boys-esque electro period, and Fenriz of Darkthrone’s exciting space albums, recorded as Neptune Towers, to Vikernes’s confession that it was the techno and house clubs of Bergen that gave him the energy to record his tracks.

Afterword

Vaporwave and dungeon synth offer their listeners different visions of an ideal world, while equally zealously denying modernity. Their message can be reduced to four simple words: “Things were better before.” They are against the modern world, of course, but we should not forget that due to their existence on Bandcamp and YouTube, dungeon and vapor albums still add up to an endless soundtrack for internet surfing by the lonely and worried.

There is another side to the escapism that vaporwave and dungeon synth exhibit, which is relevant in a world of nearly unlimited access to knowledge about culture—namely, elitism, the desire to isolate ourselves from “everyone else” and their philistine tastes by building barricades from microgenres and nano cults whose adherents could gather in a single living room if they so desired. This ambition is inherent in any music lover as a particular manifestation of the collector’s mindset: after all, sophisticated collectors of sonic impressions feel uncomfortable in a crowd.

***

I was standing in the lobby of the movie theater waiting for my girlfriend. The savage interior, which resembled a level from some Polish shooter made entirely by programmers, reeked of popcorn. My gaze fell on a Paradise Productions 2001 sign bolted to a column. George Michael’s “Careless Whisper” played in the background, but in a strange, utterly plastic instrumental version. A more vaporwave moment would be hard to imagine.

Vaporwave and dungeon synth cannot change anything about the world around us. But they can provide a setting that enables us to detect this music in the tunes we hear while waiting in the queue to talk to an operator at a bank call center, in third-rate fantasy slasher films, in the tracks of Gennady Gorin, in the wails of a beggar’s out-of-tune accordion. As an optics, as an ideology, as an entire worldview, genre is able to spin the funnel back and forth in time: once we understand the genre, we are forever determined by the sound and its ideology. Listening to the music, we can become a cybernetic consciousness loaded into a simulation of the neon Miami of the eighties, or a hobbit sneaking through mazes of dungeons. And this experience can change our perception of ourselves forever.

Translated from Russian by Thomas H. Campbell.

[1] Data courtesy of Discogs. In 2016, “vaporwave” was the most popular tag among paid downloads on Bandcamp. A year earlier, MTV did a rebranding evoking vaporwave’s visual style.

[2] I understand genre as it has been conceptualized by the music theorist Franco Fabbri and elaborated by Simon Frith (e.g., Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music, 1996): a set of musical phenomena bound by formal and technical, semiotic, behavioral, social and ideological, legal and economic rules.

[3] Here we might detect the legacy of plunderphonics, whose composers violated all possible copyright conventions.

[4] See Marc Augé, Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, trans. John Howe (London & New York: Verso, 1995).

[5] Andrew Whelan and Raphaël Nowak, “‘Vaporwave Is (Not) a Critique of Capitalism’: Genre Work in an Online Music Scene,” Open Cultural Studies 2 (2018): 462.

[6] Some have argued that this, too, was a bit of malicious wittiness on Lopatin’s part: Ecco, the name of the protagonist’s dolphin, is an allusion to the ketamine-induced visions of psychoanalyst and neuroscientist John Lilly, who concluded that everything that happens on Earth was controlled by the extraterrestrial Earth Coincidence Coordination Office (ECCO). In the sixties, Lilly was funded by NASA to study ways of communicating with dolphins by way of preparing for possible contact with alien intelligences. Some of Lilly’s colleagues also claimed that his research center had witnessed cases of inter-species sex.

[7] Xavier’s name is associated with the launch of entire subgenres of vaporwave and, judging by the single from her upcoming album, the boundaries of the genre will once again be redrawn. Xavier says she wants to do something different from Floral Shoppe.

[8] Music theorist Adam Domer argues that Xavier’s treatment is better than the original.

[9] Interview with the author.

[10] However, as noted by the Russian musician Artem Voloshenko (who records as Desired and Saturn Genesis) in 2019, vaporwave concerts finally have begun to take place, whereas previously even the most famous musicians in the scene practically never performed (author interview). See also Sarah Gooding, “Inside 100% ElectroniCON, the world’s first vaporwave festival,” Fader, 4 September 2019.

[11] Grafton Tanner, Babbling Corpse: Vaporwave and the Commodification of Ghosts (Zero Books, 2016).

[12] If plunderphonics can be considered vaporwave’s forebear, then dungeon synth can easily be imagined as an offshoot of the Berlin school of electronic music, with its emphatically ascetic sound and consummate melodicism.

[13] See, for example, this live performance by the Russian dungeon synth artist Morketsvind.

[14] Although later, thanks to the discovery of the artist Jim Kirkwood, who, according to legend, gave up music in order to become a monk, the genre’s chronology was extended back to the late eighties.

[15] The phrase “dungeon synth” emerged as a stable tag only in 2011.

[16] Aesthetically and ideologically, vaporwave and dungeon synth converge at one point—in the vague realm of New Age culture.

[17] Although Varg Vikernes (Burzum) is the second most important dungeon synth artist after Mortiis, and the albums he recorded in prison are classics of the genre, we should remind ourself again that he was sentenced to prison for murdering his friend and owner of the label that produced Burzum, Euronymous, setting fire to three churches, and possessing 150 kilograms of explosives. Vikernes is widely known for his radical views, including anti-Semitic ones.

[18] This is not to play down the scandals sparked by the right-wing affiliations of certain practitioners of the genre, who have juggled dungeon synth with performing in NSBM (National Socialist black metal) projects.

[19] For example, it is worth perusing the comments to this article, which caused a heated discussion in the metal community.

[20] J.R.R Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” in The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays (London: Harper Collins, 1997), p. 150.

[21] Although, to be fair, the two camps most aggressively represented on the internet—purists of the genre who consider it a “dark art,” and connoisseurs of punk buffoonery and degrading transgression—tend to consider this a dead end.

sreda@v-a-c.org

All rights reserved. Reproducing or using the materials from this web-page without written consent of the rightsholder is forbidden.