Artem Abramov

Unsoviet Mire of Resentment

Post-punk emerged in the late 1970s and replaced punk as an experimental and more complex, syncretic form of music that crossed styles and unique musical elements ranging from rockabilly and avant-garde jazz to ethnographic recordings. But the movement was not limited to sound–inheriting modernist ideas of the twentieth century that addressed the overcoming of measured and ordered reality, post-punk made us of a numberof avant-garde methods in the design of records, performances, and advertising.

This issue of V–A–C Sreda online magazine publishes a text written in the summer of 2021 by Artem Abramov, a journalist, cultural studies scholar and editor at SHUM Publishing. Drawing on Greil Marcus, Simon Reynolds, and Mark Fisher’s key texts on the music and culture of post-punk, Abramov reconstructs the anglophonehistory of the genre and compares it with its Soviet iteration,. and puts forward a theory as to why the contemporary Russian scene is the full-fledged heir of neither.

The summer of 2021 saw the publication of two Russian translations of books dedicated to post-punk: Simon Reynolds’s Rip It Up and Start Again, which, when originally published in 2005, brought what had been up until then a decentralised genre into a more or less organised canon, and Mark Fisher’s Ghosts of My Life (2014), which addressed not so much the sounding images of the musical expressions of post-punk culture as it did an ideocentric analysis of what moved it and what this culture relied upon. On the one hand, these translations of Reynolds and Fisher came at the right time: in the summer of 2021, Russia could boast of a diverse stratum of post-punk groups popular within as well as without the country. On the other hand, these translations were somewhat late.

Post-punk enthusiasts and “experts” read Rip it Up long ago. And we are not just talking about the translation Ilya Miller passed around within “his” circle and on which the existing official translation is based, but about arrangements made on domestic Imageboards in the early 2010s (albeit rather clumsily), not to mention some enthusiasm for the original in the past decade. In the case of Ghosts of My Life, the situation is even more full of irony. The domestic intelligentsia, turning en masse to Fisher’s writings after his suicide, soon discovered them to be extremely hermetic. And not just in relation to the topics touched upon by the deceased, but in relation to questions of territorial and cultural belonging, which did not always allow for analogues in domestic realities. And this only became all the more the case in the realities of today’s domestic post-punk.

If one opens YouTube and enters the search term “Russian post-punk,” one finds dozens of videos in the “Russian Doomer Music” category—featuring mainly the same kind of dark rock-music based on the repetition of nearly identical melodic phrases, with a no less monotonous textual component about a solitary, regular life in the stasis of an urban neverwhere. A logical question arises: how has a prolific, diverse, geographically and thematically heterogenous genre with more than forty years of history come in Russia to be inextricably associated with a narrow, albeit now widely-used internet meme?

What is “post-punk” according to Reynolds and Fisher? A syncretic musical genre that existed primarily in the anglophone sphere (Great Britain, the United States, Australia, and, with certain reservations—West Berlin) in the period from 1978 to 1985. Its sources include the Black music popular at that time on both sides of the Atlantic (soul, funk and disco, reggae/dub, and, a little later, hip-hop and electro); 1960s psychedelic and garage rock; 1970s glam; experimental sound in a variety of manifestations from post-war academic avant-garde to German krautrock; and jazz, from its early dance variations to complex improvisational works. Plus a number of unique and varied components, selected by different groups and performers: from rockabilly, which was abundantly replayed by the Manchester band The Fall, to ethnographic recordings—Middle Eastern and North African music was actively integrated into compositions by at least Los Angeles’s Savage Republic and Nottingham’s C Cat Trance. And, of course, punk. But by this term Reynolds [1] and Fisher [2] understand not fast guitar music with striking riffs and short timings (though individual groups and performers relied entirely on such a sound) but rather the impulse that brought this music into being. An aspiration to accomplish something with limited resources, with one’s own hands, to have a lot of fun in the process, and to make the process itself, along with its result, a public matter. To make sure that things are not boring. At the very least, for yourself, even better, for others.

“What is punk?” is a special discipline of creative dispute that remains popular in both foreign and domestic communities. Reynolds and Fisher draw on the American journalist and critic Greil Marcus’s theory according to which punk, despite its initial nihilistic view, has a long line of antecedents. First of all, punk is the inheritor of the modernist avant-garde of the twentieth century. Of the Situationst International, which challenged the measured and orderly spectacle of an organised reality that did not allow for situations, for chance and spontaneous manifestations of life. Of Lettrism, the father of Situationism, which rejected the automatism of everyday language. Of Dada, which questioned the value of so-called art and its superiority to practical and (seemingly) meaningless activities. Marcus traces this genealogy right up to the Christian and Islamic heretics of the Middle Ages, and builds not a territorial but a supratemporal community of outcasts, mavericks, and zealots. Punk was moved not by a desire to disrupt the existing (and invariably unfair) order of things, but by an attempt to work through modes of communication—as intuitively understandable to those who as a minimum wish others an interesting coexistence as it is inunderstandable to those who hunger for power and control—and, in parallel, to undermine any system of government by those who use this language at a given time [3]. Metaculture. A specific mode of thought, as Felix Sandalov notes.

Post-punk was well aware of its modernist heritage and commonality. More than this—it cherished and nurtured it. The manifesto was a common instrument of Anglo-American post-punk: whether it announcement the true cost of self-recording and reproducing or proclaimed the new era of man. The “cut-up” method coined by Tristan Tzara and later adapted by William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin was no less common a practice in the genre. And not just with regards to the textual component, but to the musical one—groups from the Industrial Records label were among the first to make use of analogue sampling in pop-music. Repetition (both as a textual method in the spirit of Gertrude Stein, and as a musical technique in dub and academic minimalism), Brechtian functionality of entertainment, Luigi Russolo’s recognition of noise as a self-sufficient musical unit—post-punk operated with a wide set of modernist means, improved them, and did not hesitate to use them outside of pure music: in performances, in record design, even in the advertising of the latter. Post-punk overcame punk, which had very quickly become boring, just as modernism had overcome what had seemed to it an outdated modern.

And this wasn’t just about music. The Manhattan No Wave movement showed remarkable cinematic activity. Talking Heads’s David Byrne was highly interested in theatre. The artist Jean-Michel Basquiat and the writer Kathy Acker were two other post-punk artists who, though not primarily known for their stage and musical experiences, both had them.

And this wasn’t just about art in the highbrow sense of the term. Post-punk very quickly built its own infrastructure. If punk had created a media hype but relied on specialised distribution points for musical products and on homemade press, then post-punk went much further, not forgetting about the aforementioned grassroots communication. Britain’s leading music papers (Sounds, Melody Maker, New Musical Express) very quickly acquired writers promoting the movement, both from among their existing employees and by taking on new journalists from music fanzines. Geoff Travis, owner of London’s Rough Trade record store, built up an extensive network of independent record distribution. Alan Moore, an active participant in the 1980s Northampton independent scene, was friends with the Bauhaus band and asked their bassist David Jay to compose the soundtrack to his comic V for Vendetta, giving it a completely new dimension. Cabaret Voltaire were elated by the idea of creating a platform analogous to 1960s pirate radio, only broadcasting television shows: the original idea failed, but their Doublevision initiative succeeded in creating video art. Post-punk also had its agents on television. Rick Mayall, known to Russian audiences for his episodic appearances in Blackadder, would calmly pitch his ideas to the BBC up until the mid-1990s, and his first sitcom, The Young Ones, was dedicated to the absurd life of post-punk youth.

Records and cassettes simply proved the most long-lasting, convenient, and pervasive medium of post-punk. For a time, post-punk culture flourished on both sides of the Atlantic, comparable in influence to the psychedelia of the 1960s, but more enduring. And, most importantly, this culture was far from being counter-cultural. Post-punk did not see the world as monstrously wrong, but was fully convinced of the possibility of its gradual change through modest forces. And it was actually changed—musically, at least. Even countries with strong musical cultures of their own could not resist these records of what was a strange, outlandish, even wild music for that time. One of the most unusual scenes would develop in Japan. France, having despatched its Métal Urbain group to Rough Trade (their 7” was one of the label’s first singles), met Joy Division concerts with delight. The Parisian group Orchestre Rouge would go on to record with Factory producer Martin Hannett, after which cells in love with the new sound activated across the country. And they went on to infect Brazil. Very soon, Germany had become post-punk’s continental homeland. Dozens of groups appeared all across Italy. Finally, through diplomats and sailors, recordings of this new music reached the Soviet bloc—and under their influence, new groups appeared in Poland, Yugoslavia, and the USSR.

This geography is entirely unsurprising. Post-punk was born together with social disunity, the strengthening of conservative positions—the election of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, the economic crisis in Britain, a new round in the Cold War. Japan in the 1980s was a country of maximal social stratification, and its economic boom in the second half of the decade saw an unprecedented rise in prices. The French left-wing reforms of the 1980s failed, and this, coupled with an influx of immigrants and the further establishment of a coalition government, led to social destabilisation. West Germany in those years was the main European front in the Cold War, a territory of political and economic espionage and widespread paranoia. The turn of the 1970s and 1980s in Italy saw the continuation of open and behind the scenes confrontations between communists and neo-fascists which had been on going since the spring of 1968. In the first half of the 1980s, Brazil was a full-fledged military dictatorship. Poland, at the very beginning of the Jaruzelski regime, was also under martial law, which had been introduced to combat the worker’s unions. Yugoslavia had begun to be torn apart by ethnic conflicts, though these had not yet become violent. The USSR saw real stagnation in the economic and social spheres at the beginning of the decade, the death of three general secretaries and of a number of lesser bureaucrats, and the crush at Luzhniki stadium during the Spartak-Haarlem match of October 20, 1982, the Chernobyl disaster of 1986, and the string of coffins sent back from Afghanistan.

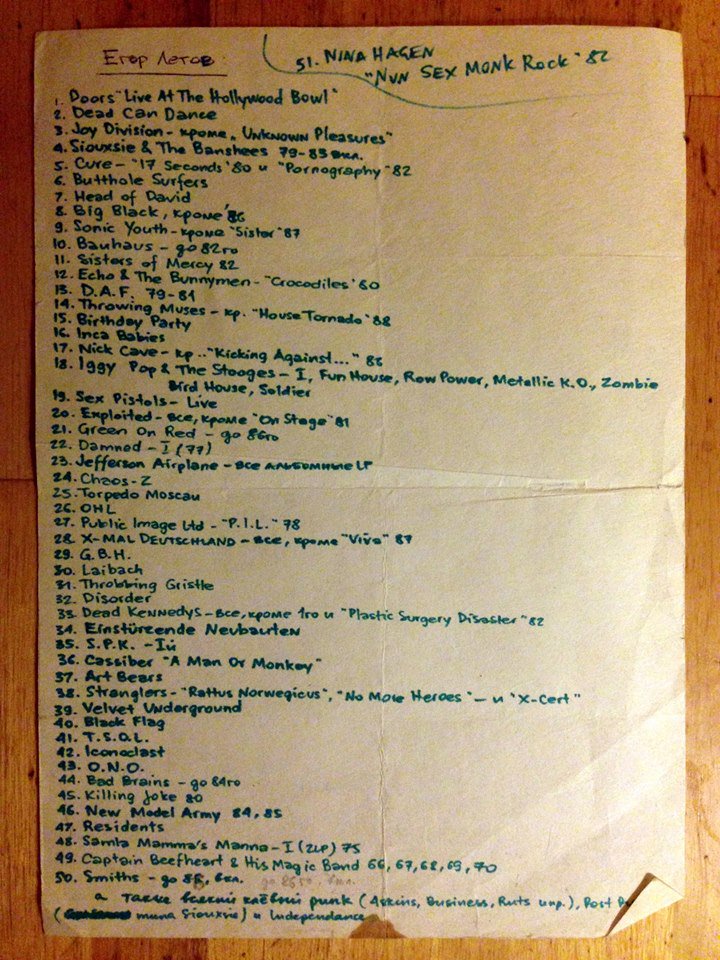

In Poor But Sexy: Culture Clashes in Europe East and West, Agata Pyzik notes that post-punk appeared in the Eastern bloc at the same time as punk, and was not seen as separate from it [4]. At first, the term was barely used in the USSR. Speculators trading in the latest records used a single term to refer to all Western music from the break of the decade. Punk (it didn’t matter whether guitar or synthesiser), along with the smooth guitar pop that was born out of it but had turned away from its bright, dark elements, and post-punk, which had based itself heavily on its dark sound—all were termed “New Wave” in the Soviet Union and considered a single artistic movement within rock music, different only in the means used [5].

Sasha Skvortsov, the guitarist of Durnoe vliyanie (Bad Influence), recalls that though one had to go to particular people for Xmal Deutschland or Siouxsie & the Banshees records in Leningrad, getting hold of them was more than possible, even if one did have to travel to Avtovo and Devyatkino [6]. Through intermediaries, Alexander Lipnitsky of Zvuki Mu (Sounds of Moo) copied live performances and music videos of Talking Heads, Joy Division, and other prominent bands of the period from Finnish and British television, which he would then show to friends at his apartment [7].

Western post-punk’s fixation on modernism was far from accidental: many young people went to art schools in Britain, America, and Germany simply because they were places where one could easily find people who wanted to play in a band along with the necessary instruments [8]. Young people from the working classes who wanted to avoid factory work and young people from the upper classes uninterested in finance and jurisprudence were introduced to the art of late modernity at these schools. This included non-academic literature: Stephen Mallinder of Cabaret Voltaire noted that although Bowie and Roxy Music quoted Burroughs in interviews, you had to try hard to find his works in bookstores—by the late 1970s he was no longer a famous writer of the Beat generation. Graeme Revell of SPK was obsessed with critical theory precisely because it provided a perfect description of the conditions of his not-so-comfortable existence, but these ideas, again, were not readily available: Revell had attended the open lectures of Deleuze and Guattari in the late 1970s in Paris—they had begun to acquire fame but were still considered radicals and marginals far from the academic mainstream. Uncommon ideas and things have an understandable attraction for the young: demanding both temporal and material investments, they banish the tedium of the present through the excitement of search and communion.

Discussing post-punk with Kodwo Eshun and Gavin Butt at Goldsmiths on October 2, 2014, Mark Fisher argued that these uncommon ideas need not be anything new. Already created rarities can look, sound, and read completely kitsch. Through its unusualness, yesterday’s innovation can inspire those that encounter it as to how to further develop the uncommonness contained within it, and so overcome its obsolete form [9]. Might this not have been why the Gang of Four eschewed tube amps, turning instead to a fat-free, danceable, yet restrained form of funk with transistors so unlike its voluptuous original? Might this not have been what lead Daniel Miller to take over the management of Mute Records, which had originally been a joke—for the opportunity it offered to show that a full-fledged record can be composed, produced, and released by a single person, albeit one to whose address a stream of demos has recently begun to be sent? Might this not have been what led Pyotr Mamonov, having watched David Byrne and Ian Curtis, to play himself out of his mind on stage in so particular a way?

To play at something, not to play on something—the Soviets more than mastered this principle of post-punk. The artist Sven Gundlach, one of the members of Srednerusskaya vozvyshennost (Central Russian Upland), the brightest collective of that time and place, dropped the following phrase: “Srednerusskaya vozvyshennost is a cooperative for the production of songs from the waste of Soviet music” [10]. This is worth emphasising. If original post-punk reworked all popular and available music of the time within itself, then Soviet post-punk worked with a no less wide-ranging, resonating spectrum. Soviet post-punk was partly a remake of the sound of late Soviet reality: foreign post-punk, which was itself a composite music, proved an important, “uncommon” stroke in this picture, but was by no means the only one. It’s worth remembering here that post-punk (at least in its British incarnation) was music of agitation and propaganda wrapped in a spectacular, entertaining, sometimes utterly ironic form. But what was post-punk agitating for?

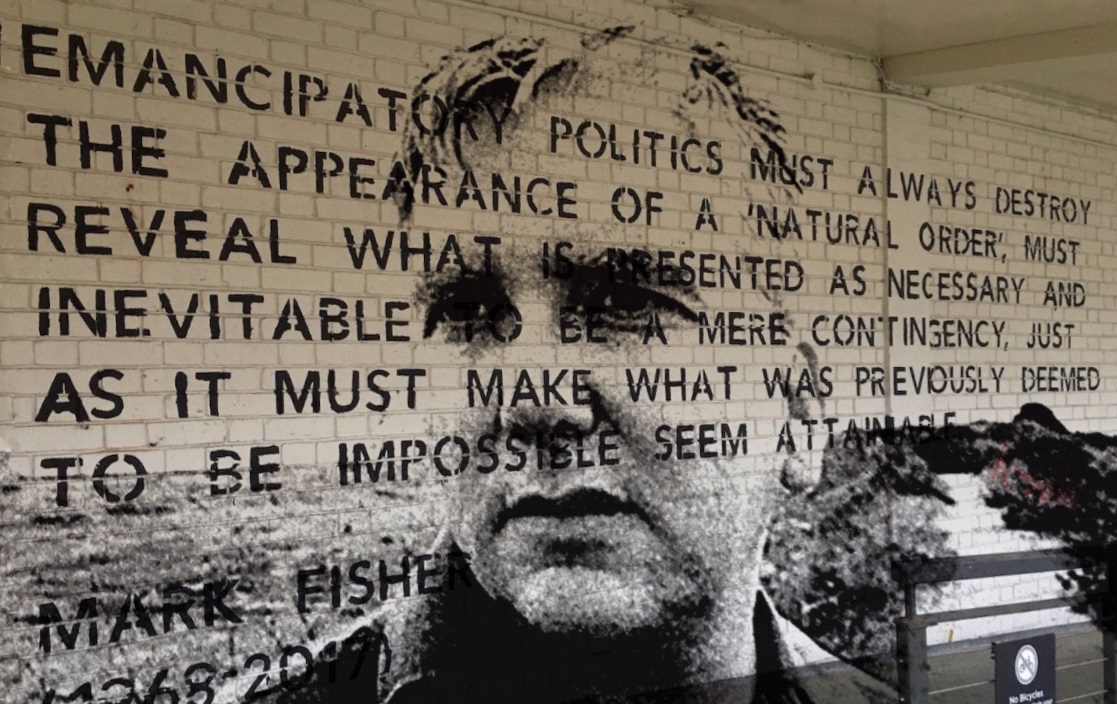

Today, the texts and the figure of Mark Fisher have been transformed from a set of instructions for the overcoming of the frustrations of everyday working life into rizomatic memes, cranked out by those whose organisations of work are cardinally at odds with the aspirations of the British culturologist. In the end, this is not so bad—Fisher had after all insisted on the consistent memetisation of reality. The main thing was that these memes, as stable units of information, were still able to express his main thesis:

“For all its carnivalesque departures from everyday reality, however, this is no remote utopia. It feels like an actual social space, one you can imagine really existing. You are as likely to come upon a crank or a huckster as a poet or musician here, and who knows if today’s crank might turn out to be tomorrow’s genius? It is also an egalitarian and democratic space, and a certain affect presides over everything. There is multiplicity, but little sign of resentment or malice. It is a space for fellowship, for meeting and talking as much for having your mind blown. If ‘there’s no such thing as time’ … then you are not prey to the urgencies which make so much of workaday life a drudge. There is no limit to how long conversations can last, and no telling where encounters might lead. You are free to leave your street identity behind, you can transform yourself according to your desires, according to desires which you didn’t know you had.”

This was how, near the end of his life, Fisher wrote about “acid communism”—a popular modernist idea of the 1960s embodied in post-punk (and, a little later, in rave, the devoted supporters of which came out of post-punk circles, if we remember only the organiser of the Berlin Atonal festival Dimitri Hegemann or Graham Massey, the guitarist of Biting Tongues who would go on to found the acid house project 808 State). Fisher’s thought resembles a citation from Grant Morrison’s comic The Invisibles (Issue #8, 1994) almost point for point:

More a desire for politics than politics itself, more an enjoyment of the thought of utopia than a desire for utopia itself. Invisibles came out from 1994–2000, during the time of what was first a social, then a political triumph for the New Labour movement in Britain. In Post-Punk, Politics and Pleasure in Britain (2016), David Wilkinson notes that the rhetoric of desire and enjoyment adopted by Tony Blair’s party from pop-culture of the 1980s was what became the chain that allowed Blair to ensure the attention and support of the masses without putting a strong emphasis on “hard” left ideology [11]. The bright future promised by post-punk arrived in Britain in the middle of the 1990s. And if this future was highly attentive to the widening horizon of consciousness provided by technology, entertainment, and work, it was not at all interested in communism. The communist images in British post-punk, from Test Dept’s call for the mobilisation of workers to the infatuation with the GDR of Mark Reeder, who was the musical connection between Manchester and Berlin, turned out to be no more than a concomitant nostalgia that became redundant after the fall of the Berlin Wall. But did those watching the flattening construction of communism want the same?

Even without listening very carefully to Muhomor (Flybane, the hooligan sound collage project that preceded Srednerusskaya vozvyshennost), or to Koka (the creative union of sound engineer Nikolai Katkov and guitarist of Grazhdanskaya Oborona [Civil Defense] and Promyshlennaya arhitektura [Industrial Architecture] Dmitry Selivanov) which was inspired by it, or to Letov’s Communism, one notices an interesting thing. Soviet post-punk music turned out to be the exact opposite of its Western progenitor: it took the slogan form of agitprop and turned it into ironic entertainment. And it did so at a time when no one took communist agitation and propaganda seriously any longer. One need only look at the performances of the AVIA (AERO) collective to see that this cross between a pioneer line and a Shostakovich ballet was an unbridled spectacle. A spectacle that young people from Moscow and Leningrad to Omsk and Magadan longed for. Auktyon and Strannye Igry (Strange Games), who dug up French surrealist poems from anthologies and turned them into slogans, did so not for reasons of their direct political potential, but because they lived through boredom in a way unusual for the late stagnation and early perestroika social reality. But in a way well-known to past generations of dissidents: communication based on entertainment, and not just on “serious” matters—here figures of Soviet post-punk coincided with their foreign colleagues [12]. The country was entangled not just in reel-to-reel tapes of re-recorded albums, but in a whole network of samizdat music magazines, the topics of which often went beyond the limits of the new sound [13].

Even the end of 1991 was unable to break the post-punk community networks, which promised many more means of entertainment and recreation than post-punk culture offered. The rave scene that had only just begun in Russia, blossoming pop-music, and various styles of metal guaranteed citizens of at least the RSFSR no less enticing and interesting leisure, and one that was more massive [14]. But Soviet post-punk evolved quite introspectively: outstanding finds on a purely sound-level were levelled by the communicational peculiarities of the cultural sphere at that time. The open competition of music scenes meant that the management of the newly opening clubs preferred to invite newer musicians. The extent to which this music was relevant outside of its recreational function is an open question. But this turn of events forced the post-punks to actualise themselves and organise their own venues for performances. Besides, no matter how eminent the people playing this music were, no matter how eccentric the audiences they attracted, in the new Federation, where it was now possible to take in as much entertainment as one could swallow, people proved very discerning in what they took in as entertainment. And so, despite being well-versed in the developments of the musical world and its continued crossing of styles ranging from post-hardcore and noise rock to avant-garde jazz and experimental electronics, post-Soviet post-punk proved conservative music. Music that was accessible and/or interesting to too small a number of people outside initiates of the genre. This, despite the efforts of N-number of journalists, was what happened to many Ukrainian representatives of the genre, who mastered electroacoustic, free-folk, and noise music, but only met the popularity they deserved long after they deserved it [15]. And this only if the performers of such music did not close in on themselves completely, as happened with the Izhevsk scene, which zeroed in on IDM and other pseudo-progressive electronics [16].

In the book Rok. Piter. 1990-ye (Rock. Petersburg. 1990-s), the vocalist of Ankylym Ilya Alekseev notes that the notorious logocentrism of Russian rock of that spill, which would later be canonised by Nashe Radio (Our Radio), grew out of the textual interests of stars of Russian rock who began their careers after the end of the 1980s— Alisa (Alice), Nautilus Pompilius, and so on [17]. However, as has been noted above, this was true not just of the Soviet iteration of the genre, but of its foreign predecessors, who were also deeply transfixed by read ideas and images. The revival of post-punk in the 2000s was also highly logocentric. Indeed, both at the time of and after the publication of Rip it up and Start Again in 2005, a number of blogs on the Blogspot platform (Reynolds ran his own blog there) covered the genre’s signature records. As they digitised and posted recordings on their platforms, bloggers reflected on the history of the genre with visitors, often also with the musicians themselves—who were sometimes extremely surprised by the surge of interest in their music—blogs like Phoenix Hairpins, Mutant Sounds, and Systems of Romance sometimes covered things that had received almost no attention at the time of their release. The Russian segment of the Internet also had its strong points on this topic—specialised communities on LiveJournal, the personal blog of industrial musician Dmitry Tolmatsky, and the Grave Jibes fanzine. An abundance of information about this music was accompanied by a wave of reissues of iconic records. For the first time, enthusiasts of this particular musical phenomenon had access to both a catalogue of this phenomenon and to a solid base of texts about it, and this provided the initial impetus to the Russian post-punk revival.

In 2011, the VK “E: / music/ ” network was launched. Its post-punk network was one of its most active almost from the moment of its creation. Using the above mentioned and other blogs, as well as the Rateyourmusic service, which allows users to search for albums by genre and year of release, admins uploaded masses of musical material daily, which immediately ended up in user players. The hosts of “Songs of Joy and Happiness,” which appeared in early January 2012, did almost the same thing—they published the domestic branch of the genre, mainly with an eye to its “existential-Siberian” part. Thousands of people—dozens of whom later created their own groups—realised that playing such music was not just very simple, but also appropriate—it already had a base of many young and not so young people awaiting new records in the resurrected genre.

But let us return to geography. It was not without reason that Fisher and Reynolds singled out 1985 as the end of post-punk—and this was not so much because of the penetration of the genre’s methods and sound techniques into the relative mainstream, as because of the defeat of its ideas of “popular modernism” in the face of right-wing populism. In 1985, Thatcher definitively broke the miners’ unions strikes, with which the youth had joined in solidarity. In the same year, Ronald Reagan was re-elected to a second term in the United States. Reynolds links the early to mid-2000s—the starting point of the American post-punk-renaissance—to a strengthening culture of rereleasing albums of the past and to a simultaneous disillusionment with the Western conservative turn: fatigue from the political course of George W. Bush. The last five years of British guitar music have taken place under the banner of “Brexit-Core,” a new wave of post-punk that has been highly attentive to events in the country since the June 23, 2016 referendum. But the majority of the Russian post-punk acts that are popular today or were so five or ten years ago appeared as a result of utterly different events. The failure of Russian pop-music’s “European Project,” the reorientation of the domestic pop-industry to the Western genre market. Starting in the middle of the 1990s with the imitation of Britpop and foreign alternative rock, the “European Project” ended at the end of the 2000s, when it became clear that anglophone domestic indie-rock and related music was doomed to be a niche product even at home. The new Russian post-punk that came into being in the early 2010s perfectly embodied the bitterness of defeat of the capital’s pop-industry. It was not without reason that a significant number of these groups arose in the million-plus cities of the European part of Russia and in Siberia. This was the music of an in-between-time that was in despair at not knowing what to do with itself—and for this reason, it concentrated on pure description of the world around it.

However, the despondency and fatigue noted as the key mindsets of Russian post-punk by Daniil Kiberev could not only have emerged from the experienced political background. Artem Rondarev states that the hero of today’s Russian post-punk is the flaneur, the man without a face, who notices the structures of surrounding reality in its material manifestations, in landscapes and architecture. However, the post-punk flaneur of twenty-first century Russia is not the flaneur of the nineteenth century, not the bored bourgeois well-versed in the finer details of the architectonics of buildings belonging to the aristocracy to which he has no access. The post-punk flaneur is a representative of the working (or adjacent) classes who surveys old, functional buildings, the purposes of which he often remains unaware of, along with residential buildings and spaces of the modern city. There is not much difference between them in his eyes, perhaps even none. If one listens to the first two mini-albums of the Ekaterinburg group Gorodok chekistov (Chekist Town), released in 2010 and 2012 respectively, to Novostrojki (New buildings), the 2015 debut album of the Ploho collective, and to Kitezh (2018), the EP of the Nizhny Novgorod band Iyul'skie dni (July Days), one notices a curious thing. Despite a considerable time span, in the musical space of these recordings, the city is depicted in a very similar way: related feelings of nostalgia and desire for escape amidst a mass of identical buildings with a similar purpose, in which the signs and markings of time lose themselves.

It is in this that contemporary Russian post-punk is so unlike its forerunners. Original post-punk was itself a revival, it sought to preserve cultural memory of mass events and phenomena of the twentieth century despite the pronouncements of British, American, and Soviet politicians who promised future prosperity at the cost of abandoning or reassessing the past. Russian post-punk-revival music, however, turned out to be not just conservative, but a musical means of conserving an unmusical aesthetic of general stasis and ongoing unrest in an indefinable urban ghetto. It sings of individual seclusion on a fortress-island raised from the works of an identical but temporally elusive culture.

According to Marco Biasioli, this aesthetic formula, encased in a “casus Joy Division” sound shell, proved in high demand not just domestically but in the export field, and whole regions (for example, Latin America) became fertile markets for the sale of such music [18]. And not just Russian music—Belorussian groups like Molchat Doma (Houses are Silent), Nürnberg, and Dlina Volny, released by the Western labels Sacred Bones, Death Shadow, and Italians Do It Better respectively, also had success. This turn is surprising in light of the fact that foreign and domestic post-punk was not careerist music, many of its representatives held as a minimum restrained attitudes towards capitalist models of society, if they did not try to use it. For those musicians who did not become world famous and did not continue to make music in their original groups after a decade or so (and few of them did), post-punk was simply the starting point of their careers. Sergei Zharikov, leader and ideologue of the DK collective, turned into a political strategist. Linder Sterling, the one time front woman of the Ludus group, has made a name for herself an artist. Gleb Butuzov, co-founder of the Kyiv group Kollezhskij asessor (Assessor of Colleges) is known today as a specialist translator of works on the Western esoteric tradition. Blaine L. Reininger of Tuxedomoon is an established academic composer. Ilya Kormiltsev of Nautilus Pompilius would become known as a poet, publicist, and publisher. Over time, post-punk became more than influential music in the Western pop-culture canon (this is confirmed as a minimum by the YouTube channel Trash Theory), but this took place at least two decades after the birth of the original genre. Why is it that modern Russian post-punk, after a couple decades, has legitimised the same game of paperwork that only John Lydon at Public Image Ltd could initially afford? Yes, a few teams with a lower status?

Because it is very distinctive, understandable music. And on the level of musical vocabulary—bands like Shortparis, Buerak (Ravine) or Human Tetris are not inclined to merge and be acquired by the rest of modern music—instead, they exploit the discoveries of forty years ago and sound them using the possibilities of modern studios. And on the level that it is intended to shade or duplicate. Returning to Greil Marcus’s thesis of post-punk as a characteristic language code, in modern domestic post-punk few people play the fool, swear, or sting. Almost no one is “talking in mythic language,” in the words of Eyeless in Gaza’s Martyn Bates [19]. But everyone strives to be either intelligible and accessible, or to master a mannered Aesopian language. To describe and grasp an already existing reality, not to elementarily invent something. The journalist Petr Poleshchuk considers such sincerity to be directly opposed to post-punk as a method: the editing of reality. Subtle work with the landscape of any communications through persistent broadcasting of doubts about the operation of the constructs of social and individual consciousness, expressed in many different ways.

“Russian Doomer Music” no longer edits reality, it only corrects it: lubricates and grinds all the unevenness of domestic life into the uniformity of a monotonous rock-music with synthesisers and guitar tremolos, turned in not even on itself, but on its unchanging state. Such easily understandable and accessible music can be highly interesting in terms of banal commodity-money market-economic relations, but. The Perestroika Council of Ministers of the USSR openly used Soviet post-punk as a showcase for the achievements of cultural economy. Showcasing the musical culture of previously marginal people as an exclusive good, advanced and competitive by world standards. And this despite the fact that representatives of this culture had never found a single kind word to say about the Soviet Union.

“Russian Doomer Music,” despite all its popularity within the country and outside of it, makes no pretences to political or social statement—simply to an existential manifestation of itself. Kiberev, however, is more than certain that the current state of domestic post-punk (or Russian Doomer Music, however you’ll have it)—is already a guarantee that something alive will eventually appear on this concrete island, from those tired of its uniformity. And, perhaps, he is right. If you turn away from the popular streaming algorithms, you find many other things.

Ironising about the 1990s–2000s–2010s “continuum of panels,” Yaroslavl’s Ispanskij styd (Spanish Shame) accompanies this irony with desperate synthetic funk. For five years already, GSH has played his mosaical avant-rock, and doesn’t hold back from revealing what gives which particular sound. Khabarovsk residents Rape Tape chase their noise dub. Saint Petersburg’s Studiya neosoznannoj muzyki (Unconscious Music Studio) and Atomno-hrustal'nyj karnaval (Atomic Crystal Carnival) go further and further in their attempts to cross dance guitar music with idiomatic improvisation and club sound. Anything that falls into the hands of EVA2O37 and Marzahnn rattles and buzzes. Tambov’s Yama (Pit) and Sergiev Posad’s Cage of Creation knead fractured rhythm sections on different types of metal; though not in the way that became popular in the heavily metalised gothic-rock of the West some time ago [20].

It’s splendid when someone realises that we not only live long after punk, but also left post-punk behind some time ago.

Summer 2021

Bibliography:

[1] Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978–84 (London: Faber and Faber, 2005).

[2] Mark Fisher, “Autonomy in UK,” in k-punk. The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher, ed. Darren Ambrose and Mark Fisher (London: Repeater Books, 2018), 562.

[3] Greil Marcus, Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989).

[4] Agata Pyzik, Poor But Sexy: Culture Clashes in Europe East and West (Alresford: Zero Books, 2014). See in particular the chapters “Ashes and Brocade” and “Mystical East.”

[5] Misha Buster, KHULIGANY-80: Chast' pervaya “N’YUVEYV” (Hooligans-80: Part one “NEWWAVE”) (T/O NEFORMAT, 2016).

[6] S. Skvortsov, Eponymous. Odnoimennoye proizvedeniye (Eponymous. A work of the same name) (Saint Petersburg: Renome, 2016), 27–34.

[7] S. Guryev, History of the Sounds of Mu Group (Saint Petersburg: Amfora, 2008). See in particular Chapter III.

[8] Simon Frith and Howard Horne, Art into Pop (London: Methuen, 1987), 27–30.

[9] Gavin Butt, Kodwo Eshun, and Mark Fisher (eds.), Post Punk Then and Now (London: Repeater Books, 2016), 8–10.

[10] See the booklet that accompanied the re-release of the group’s album Chetvertyy son Very Pavlovny (The Fourth Dream of Vera Pavlovna) on CD (Otdeleniye VYKHOD, 2016).

[11] David Wilkinson, Post-Punk, Pleasure and Politics in Britain (London: Palgrave Mccmillan, 2016), 189–191.

[12] Samples of experimental perestroika cinema in which Soviet post-punk figures often had a hand can be found on the Paracinemascope Telegram channel.

[13] The third issue of the magazine KontrKul'tUr'a, published in the very last days of the USSR, contains a detailed if incomplete review of Alexander Kushnir’s criticism, published by samizdat.

[14] Despite the long-lasting, nationwide popularity of metal music sub-genres in Russia, this topic continues to await its researcher.

[15] Representatives of the post-punk “New Scene” in Ukraine in the 1990s and their music can be found in the compilations “Charkow Underground” (in two parts, Kentucky Fried Royality, 1991), “Novaya Scena: Underground from Ukraine!” (What’s so Funny About.., 1993), “Shovaysya” (Get away) (PDB, 1995) and “Guchnomovets': Sbornik Kiyevskoy rokenrol'noy muzychki” (Collection of Kyiv rock-n-roll music) (samizdat, 1996).

[16] As well as the well-known Formeyshn. Istoriya odnoy stseny (Formation. The Story of one Scene) by Felix Sandalov, a detailed picture of post-Soviet post-punk strategies in isolation is provided by Alexander Gorbachev and Ilya Zinin’s Pesen v pustotu (Songs into the Void). The previously mentioned memoirs of Sasha Skvortsov are also presented in the books Sledy na snegu (Footprints in the Snow) by Vladimir Kozlov and Ivan Smekh (Moscow: Common Place, 2020) and Natalya Kurtukova’s Rok-n-roll na Yuzhnoy (Rock-n-roll in the South) (author’s edition, 2019).

[17] I. Alekseev, Rok. Piter. 1990-ye (Rock. Petersburg. 1990s) (Saint Petersburg: Helikon Plus, 2006), 32–35.

[18] M. Biasioli, “Ot "krasnoy volny” do “novoy russkoy volny”: rossiyskiy muzykal'nyy eksport i mekhanika zvukovogo kapitala” (From the “red wave” to the “new Russian wave”: Russian musical export and the mechanics of sound capital), in New Criticism. Contexts and Meanings of Russian Pop Music, ed A. Gorbachev (Moscow: Institute of Musical Initiatives, 2020), 308–312.

[19] Rob Young, “Patterns Under the Plough: On Eyeless in Gaza,” The Wire (278), April 2007.

[20] At the time of publication, a number of these bands have broken up and/or left the Russian Federation.

sreda@v-a-c.org

All rights reserved. Reproducing or using the materials from this web-page without written consent of the rightsholder is forbidden.