Artem Morozov

First Time Again: Time for One

V–A–C Sreda online magazine presents a new issue dedicated to the phenomenon of singularity in art, timed to coincide with the Festival of Singular Films at GES-2 House of Culture. The Festival of Singular Films features the Russian premieres of some of the finest international debut films of the year, along with a special section dedicated to classic and lesser-known films.

In this issue, we publish a text by the philosopher and translator Artem Morozov. The author examines the theme of singularity in the philosophy of Graham Harman and Tristan Garcia, using the solitude of objects and love for the Other as examples, and also turns to films, especially the film Annette by the French director Leos Carax, for whom the conflict between the “first” and the “last” is one of the main motifs of his work.

The Maiden’s Bedchamber

“In other words, things communicate only by their solitude—it is because every thing is equally alone in the world that things can be together in each other.”

The reception of object-oriented ontology has, in my opinion, proved crushing to it in most cases: the main thing in it was absolutely not the opposition of non-humans to “subjects”—humans, but purely “objects” as entities in relations constructed by them, taken apart from them, or as terms outside corresponding formulas. That is it was an attempt at non-relational thought and not so much about the content of this thought as about its form and method. This is why OOO initially argued for identity over difference, sympathetically but condescendingly regarding process philosophies and so on.

But, fairly soon, everything degenerated, that is, normalised: Levi Bryant with his objects as machines and their capacities, Timothy Morton hunting his hyperobjects and transcendental meditation on the repeal of the law of contradiction, Ian Bogost with his video game consoles. All of them, in one way or another, reinscribed objects, in their very objectivity, into relational frameworks instead of showing how these frameworks (and not concrete instantiations: “networks, ” “systems of interactions, ” interfaces) are “in principle” generated and imprinted by objects—through their formal ontology as self-willed individuals who are both principles and adherents of themselves before any individuation.

The heart of Harman’s philosophy is love. On the one hand, as he often repeats to us, given philosophy is love of wisdom, and not wisdom itself, we are denied real knowledge of objects as they are in reality. Love turns out to be something that marks an irreducible distance: you cannot love something that you possess, love for wisdom is always unrequited. On the other hand, for Graham Harman, as for Dante—the former wrote a book on the broken hammer of the latter titled Dante’s Broken Hammer—the world is driven by love. Here is what one ends up with: all unions of objects, even the most quarrelsome, all relationships into which they nevertheless indirectly enter into with one another, are love as the most direct and immediate form of sincerity. Well, let’s at least suppose so.

However, this sincerity arises between a real and a sensual object, for example, between me (my “real I”) and the sensory image of some person (animal, process, event, object…). And this sincerity arises precisely out of a double withdrawal from the sensual sphere, double inaccessibility (Heidegger’s mechanism of Entzug, or withdrawal)—the withdrawal of my “real I” and the withdrawal of the real object, which is in a peculiar non-relationship to its sensual counterpart, through which I hope to experience feelings toward it—and I can only hope that these will be feelings directed to the other and not at its collective image, encrusted with sensual qualities, or at these ephemeral qualities, or even at real qualities, existing independently of my perception, whose bundle cannot be reduced to it.

Does this mean that love is only a kind of ghostly bridge? Not at all: a one-sided intentional union, taken apart from terms exists as a separate object or certain term. It cannot even be said that the love is mine, given the object-union is separated from me in its reality. It eludes me, I no longer possess it, although I seem to generate it, only I don’t understand exactly why. The truth is that the solitude of objects is only increased by the unions they produce: where there is union, there is also separation, where there is sincerity, there is also incessant doubt: the more one desires to be outside oneself, the more one falls inward, isolated from what one (would like to) consider both oneself and one’s own.

It would seem that something similar is said in Form and Object by the French philosopher Tristan Garcia, who Harman joyfully rushed to call a representative of “object-oriented France.” Garcia bases his formal ontology on solitude, and it is precisely solitude—and not unity, not even identity, for example—that characterises a thing taken as a thing purely formally, as something separate in general and not something concrete in particular —as “no-matter-what.”

The French phrase “n’importe quoi” is akin to the Russian “whatever its name is well, that one, ” that is, something like a gizmo you ask your friend to pass to you or ask whether they’ve seen, whose name hovers on the tip of your tongue, but just won’t come, just like the immemorial answer to the question about the essential existence of a person-thing, the answer to the question addressed to you by it: what do you love them for, what is special about them?

It would seem not for any particular trait, but even if so, for the “the Devil knows what, ” this je-ne-sais-quoi is a trifle, “almost nothing” presque-rien, according the Vladimir Jankélévitch, a Bergsonian of Russian-Jewish provenance, who borrowed these concepts from French. Garcia clearly follows Jankélévitch when he subjects n’importe quoi to a kind of substantiation, but a subtle, weak one, placing it between nothing and an object, thereby in an intermediary zone.

Falling into consideration through this trap, you find yourself deprived of any determinations on the side of relations, of qualities constituting objectivity; according to Garcia, you become an insignificant type, not a person—a thing without properties, about which it can only be said that it is alone in the world or before the world, since “the world” is exactly everything that is not you—a complement of you not necessarily as a set or as a fact, as though you were a part that lacks something or someone, but precisely as solitude of the one-alone. And one does not necessarily mean unity, why would it need to be whole rather than in a broken or shattered state… Well, and with whom are we standing?

The feeling of solitude in people is “a meta-relation, a relation to a relation [un rapport de rapport]; shared not only by humanity, life, and materiality, but beyond them, by everything that may be, ” by everything that exists as something.

And this love of theirs as a thing (whether it be a real thing in Harman’s sense or only a thought about love) is alone in the world, yet together they cannot be alone. Garcia may seem to be making a point akin to Harman’s, but nothing could be further from the truth: for Garcia, love, although it is not the main example of connection or union as it is in Harman, is the single example of no-matter-what in the chapter on solitude—which implies reciprocal, ideal, two-sided relations: two beings (think they) love each other.

For Harman, any possible contact is strictly one-sided, although he allows the possibility that my one-sided contact with a sensual object is, in its turn, determined by a real object “corresponding” to it, luring it in its direction, as though into a trap, capable of communicating obliquely or indirectly, allusively, or through a seductive allure, Jean Baudrillard’s sense.

Moreover, love and thoughts about love also turn out to be different things for Harman, real and sensual, while Garcia’s formal ontology is absolutely flat and does not imply so strict a division of things onto two categories. The point is that for Garcia neither withdrawal nor another form of isolation exist, even though regarding love, he says that things: retire into [4] “in an isolated, withdrawn place, into a bedroom” (evidently, this is the credo of object-oriented France: a maiden’s bedchamber): a thing is not some identity drawing away from all relations, whether they be internal or external, but the difference between that which is outside it, and that which is within it, and nothing more.

But even in this case Garcia’s n’importe quoi is a significant non-essence that at first glance almost corresponds with but is ultimately far from I-don’t-know-what (je-ne-sais-quoi) and almost-nothing (presque-rien), a mere trifle according to Jankélévitch, because despite the unpretentiousness of these terms, for him they conceal the Real in all its inaccessibility and ephemerality.

…intuition, like pure love or heroic effort, lasts only an instant, that is, it does not last, but it is almost-nothing (presque-rien), a quasi-nihil — exactly an eternity compared to the absurd nihil of despair.

In Harman’s identity there remains something hidden, and it is a short step from it to objectivity according to François Laruelle, which from the underground defines our definitions of themselves as “that, which” is already defined by itself and does not need the “assistance” of transcendent, ideal definitions that would co-constitute it—such is full solitude, but for Harman, it even flees from itself. The difference in Garcia is that solitude is already emptied, and therefore exposed to itself and the world. For Harman, perhaps such a world would be an empty abstraction. Or, conversely, Harman’s object is capable of the highest kenosis because it is not abandoned in the world, but the world before it, while Garcia’s thing is doomed to the “indifference” of the world, bound to it as a supplement through a differential bridge that cannot be breached.

Garcia’s formal ontology “transforms” into an objective one when things become intense—they acquire definitions, and it becomes clear that someone loves someone more, someone someone less, or even doesn’t love, but one way or another the relationship remains two-sided, even if it is one-sided, it remains a relationship and does not become a non-relationship. Love is always already divided, although someone may very well end up with zero on division, or an infinitely small amount, but there seems to be no problem here… Yet the problem still seems persistently real.

Well yes, in another book, dedicated to “what electricity has done to thought, ” Garcia would argue that there is after all a problem; that calls to live fully and intensely, “to love as if for the first time” are problematic, but such calls flow all too conveniently from his own objective ontology, while his formal ontology does not seem to offer any resolution to this conflict at first glance, and Graham Harman’s object-oriented allure is, in turn, too murky. Moreover, as Jankélévitch would say at this point: the second time could be the second first time or, if suddenly this is not enough, the first second time.

Let The Ships Burn

“Dreaming of islands—whether with joy or in fear, it doesn’t matter—is dreaming of pulling away, of being already separate, far from any continent, of being lost and alone—or it is dreaming of starting from scratch, recreating, beginning anew.”

This tension between the “first time” and “another time, ” as well as between the “last” and “penultimate” constitutes one of the main motifs in the work of the French director Leos Carax, alongside the conflict between wholeness and fragmentation. As many have noted, not a single one of Carax’s films does not feature the image of breaking glass. And the end of Holy Motors, which seems to have foreshadowed Carax’s film Annette, contains lettristic humour referencing Mallarmé’s line “Penultimate is dead” from the “Demon of Analogy”: in the penultimate scene, Kylie Minogue’s character jumps from the roof of the Samaritaine department store near the pre-penultimate letter of the sign, while the title of Holy Motors on the hanger becomes “Holy Mot rs” due do the burnout of the third “O” (“mot” in French is “word”). This chain of self-reference is sealed with the song “Stepping Back in Time” performed by Adam Driver in Annette, the title of which coincides with the title of a track performed by a young Kylie Minogue, who in turn performs the mysterious song ”Who Were We” in Holy Motors:

I have a feeling

The strangest feeling

There was a child, a little child

We once had a child

…Love has turned into monsters and yearned to be far apart

All new beginnings

Some guy, some girl

Who were we?

Who were we when we were who we were, back then?

Who would we, have become if we’d done differently, back then?

All new beginnings

Some guy saw the world begin.

It seems as though what interests Carax most is Shakespearean time, which “is out of joint”, as in the track The Time is Out of Joint by Scott Walker that opens the film POLA X, a Caraxian adaptation of Herman Melville. The title, as is well known, is an acronym for the original title in French, Pierre, ou les Ambiguities (Pierre: or, The Ambiguities)— combined with the Roman numeral of the final, tenth version of the script. Annette is torn through with conflicts between first times (the first steps of baby Annette, her first words and so on) and repetitions or renewals (“excuse me one more time, once again”), while the main character of the film Boy Meets Girl, fascinated by all first times, plans to become a director but limits himself to the composition of titles for future scripts.

Carax is preoccupied with the poetics of titles, the relation the script-head—a kind of “writing before writing, ” to which can be addressed the question: “Who were we when we were who we were, back then?” (what roles did we as actors and actresses play then, what was the script?)—to the film-corpus as an adaption of écriture. A relationship that could be characterised as decapitation. After the first recording of the human voice in history plays in Annette, singing “Au clair de la lune, ” Carax announces:

Ladies and gentlemen

We now ask for your complete attention.

If you want to sing, laugh, clap, cry, yearn, boo, or fart

Please do it in your head, only in your head.

In the script of Annette, which has appeared online, one finds many jokes connected to this motif, for example the stage direction “a theatre audience laughing their heads off, ” while fragments from the film The Crowd by the American director King Vidor are played. And the penultimate empty page, cutting off the final scene, coincides with the credits. The particularly impatient public (“My dear public, you fucking headless beast!”—as the character of Henry McHenry, played by Adam Driver, would put it) leaves the theatre at this point.

Upon discovering this script, I was fascinated by the work of Carax and the Sparks band—to the point of a monomania that isolated me from many of my friends, who were simply not ready to rewatch, relisten, and reread the script for years only in order to rewatch, relisten, and reread the rest of the world through it afterwards.

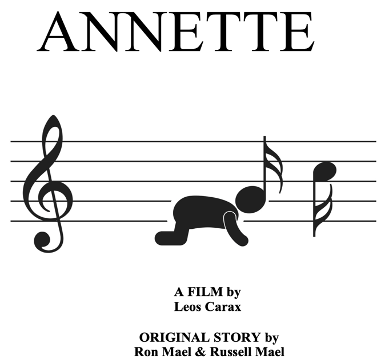

The reasons for my obsession were the title page and simple chance—which, as we know, is never annulled by the dice-throw. The point here is that a week before watching Annette I had learned of the existence of the artificial Solresol language, in which people sing instead of speaking. And the image of a child on the musical staff in the script turned out to be a riddle coded in this language:

Posing the question of the unity of a work such as Proust’s In Search of Lost Time or The Book by Mallarmé, which was to have been performed liturgically, the French philosophers Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari wrote:

We live today in the age of partial objects, bricks that have been shattered to bits, and leftovers. We no longer believe in the myth of the existence of fragments that, like pieces of an antique statue, are merely waiting for the last one to be turned up, so that they may all be glued back together to create a unity that is precisely the same as the original unity… We believe only in totalities that are peripheral.

Annette turned out to be, in my view (and also in my hearing and reading) a kind of new Gesamtkunstwerk that resulted not in a synthetic work of art, but existed in many parallaxes or resonances, in the interstices between its versions, acting on various sensory modalities and on a par with them. This object can be read, listened to, seen, but its script version can also be read and seen, and an invisible visuality, different from the filmic one, arises from the audio version, and so on.

Below I will share additional thoughts on the reasons why I attach such great importance to this work or object, assuming that the reader is already acquainted, to some extent, with the film. My theses will be somewhat disjointed and may not immediately form a coherent picture, but it couldn’t be otherwise, given “we don’t have long.”

From The Money Point of View

“This strange way of recognizing the multiple as the intrinsic difference of the one—as its singularity instead of its individuality—implies a new way of counting. This will no longer involve frequencies but, as we shall see, the money account.”

There is only one truly serious philosophical problem—the problem of deceived investors. If any political economy is libidinal, then the issue is in manipulations of libido investments and other investments, in unsuccessful swindling or unhedged false promises, in short—in the deception of the expectations of those who trusted, or creditors, though the expectations of the public could include “disappointment of expectation, ” but not just any surprise. Regarding the attente (French “anticipation”) of the public and the audience one must show complete attention, given not any auteur film is a box-office sell-out or receives a prize for best director at Cannes—The Chorus/The Crowd could have been left unsatisfied.

Traitors, as we know, end up in the ninth circle of hell, while the last ditch of the eighth is reserved for counterfeiters, along with their philosophical colleagues, alchemists, given the Great Work—the creation of the philosopher’s stone, in the case of alchemically-interpreted Orphism (the mythical equivalent would be the Argonauts’ quest for the Golden Fleece)—was also quite the scam.

Sparks and Carax’s Annette should have received a prize not for mise en scéne but for mise en abyme—a prize for the best “placing into the abyss, ‘[8] as the technique of framed narrative was called by the French writer André Gide, the author of the novel Les Faux-Monnayeurs (The Counterfeiters), whose main character writes a novel about ‘Counterfeiters.’ After all, this is not just a film about cinema in film, but an opus and opus about an opus (about itself and about the reception of baby Annette) and an opera (about the specific genre of opera in which Ann’s character performs), opus (magnum of alchemy in both the narrow and the broad sense) and an opera (about works in general).

Almost from the outset (in the recording studio; at the start of the script’s optical and auditory setting) complaints about financing are heard— The budget is large but still —it’s not enough, referencing Federico Fellini’s line “the film will be finished when there is no more money left” as money as “conventional units” constitutes the “internal presupposition” of cinema, the situation of its temporal and temporary work (cf. temp job—the Accompanist):

What the film within the film expresses is this infernal circuit between the image and money, this inflation which time puts into the exchange, this ‘overwhelming rise’. The film is movement, but the film within the film is money, is time. The crystal-image thus receives the principle which is its foundation: endlessly relaunching exchange which is dissymmetrical, unequal and without equivalence, giving image for money, giving time for images, converting time, the transparent side, and money, the opaque side, like a spinning top on its end.

The degree of sympathy for the abyss and index sui et falsi—the indicator of itself and the powers of the false—is off the charts in Annette, as is the number of revolutions of the characters around one another and around the world in an airplane (this said, only capital cities are visited). Lapis philosophorum in alchemy is sometimes equated with filius philosophorum / sapientiae, it is infans noster / (solaris) lunaris, “our philosophical (solar) lunar child, ” and this child is “of three fathers”—one of its embodiments in Renaissance mythological symbolism is the hunter Orion, conceived in a bull’s hide with urine from Zeus, Hermes, and Poseidon (or of Apollo, Hermes, and Vulcan, according Michel Maier, a sixteenth-century alchemist-adept, or Jupiter, Mercury, and Neptune, according to Dom Pernety, an eighteenth-century adept).

In the case of Annette the role of the troika of fathers is played by the duet of the auteur Carax and (the duo) of the Sparks band, in the case of creation within the creation—of the baby Annette, as a child and as a project—the triumvirate of Henry McHenry, who conducts the audience’s laughter “with a big wave of his arm (like a conductor)”; the unnamed Accompanist, a contender for the leadership of the band with baby Annette and the author of the melody “We love each other so much”; and Ann—initially a constantly dying actress, then the deceased Penultimate-autrice who descended into Hades, Eurydice haunting her husband Orpheus as a ghost or phantom (the line of the Spirit of Ann and the Image of Ann are phantasmal in the midst of Henry’s visions), and the daughter— shuffleboard (“Her voice will be my ghost”), released when artificial or lunar—reflected solar—light hits the face of the puppet baby Annette. Such alchemical imagery also permeates the essay of the French philosopher Roland Barthes The Death of the Author:

… The Author is thought to nourish the book, which is to say that he exists before it, thinks, suffers, lives for it, is in the same relation of antecedence to his work as a father to his child…

… Similar to Bouvard and Pecuchet, those eternal copyists, at once sublime and comic and whose profound ridiculousness indicates precisely the truth, of writing, the writer can only imitate a gesture that is always anterior, never original…

And Carax and Sparks mock all of this—putting words such as these in the mouth of Henry McHenry, for example:

I stood upon a cliff

A deep abyss below

Compelled to look, I tried

To fight it off, God knows I tried

This horrid urge to look below

But half-horrified

And half-relieved

I cast my eyes

Toward the abyss, the dark abyss

I heard a ringing in my ears

I knew my death knell’s ugly sound

The overbearing urge to gaze

Into the deep abyss, the haze!

So strong the yearning for the fall

Compare with Edgar Allen Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, to whom Carax expressed gratitude in the credits:

There was a ringing in my ears and I said, “This is my knell of death!” And now I was consumed with the irrepressible desire of looking below. I could not, I would not confine my glances to the cliff; and with a wild indefinable emotion, half of horror, half of a relieved oppression, I threw my vision far down into the abyss… in the next, my whole soul was pervaded with a longing to fall; a desire, a yearning, a passion utterly uncontrollable.

The triads of authors and actors described above are connected—externally and internally—by messengers (in the script they are identified as the Announcer and the Announcer’s voice), that mainly reside in the liminal spaces of corridors and passages behind the scenes, including out of frame, as well as in the gaps between the optical and sound images along with the technical team: opera technicians, some invisible technicians, crews of technicians, and the Accompanist as the one with the technical expertise, in contrast to the Voice of Ann and Ann herself as, respectively, the one with the genius, and the one with the grace.

“Genius, ” as a roman variation on the the Greek “daimon” is close to the ghost voice with which Ann haunts Annette; the Jewish Hannah—“grace” and St. Anne—the mother of the Virgin Mary, who, due to her fleshly kinship with Jesus, numbers among the “God-bearers”. Besides the Accompanist, the most important messengers are the voices of Leos Carax (at the very start, before his appearance on screen); of Connie O’Connor, the speaker of the ShowBizNews announcements that divide the film into four acts; and the black host of the Hyper Bowl HalfTime Show from the climactic scene at the stadium.

Henry McHenry’s stand-up show also thematises creativity in general—its title, The Ape of God, references not just the devil, but also the singerie (monkey business) of the Baroque and Rococo styles—plots with painting monkeys (and accordingly also to the end of Holy Motors). This, along with the toy imagery of the film that references the figure of Georges Méliès, the director of the film A Trip to the Moon, who became a toy seller after the failure of his films—is also mise en abyme, but in the heraldic sense: a miniature copy of the coat of arms on itself. The opera The Forest is doubled by the location of the same name, the Forest beyond the city of Angels, Los Angeles, the mediatised world of Annette—out of this world along with the Sea, the Court, and the Prison.

It is also doubled by the island on which Henry and baby Annette and Master and his Pen finds themselves after a shipwreck, after which Henry is consumed by the idea of a tour of the world in pursuit of aura, and, after, by the idea of a journey home to Europe, from the New World to the Old, a reversal of time and return to his youth, creative powers, and love. The island is a kind of edge of the earth, finis terræ, the end of one world and possible beginning of another.

So let the ships burn, we are always alone with you

You and I—a deserted island

And here I am forced to to take my leave until next time. “Excuse me one more time, ” although I have said almost nothing about the object of my love… but let’s sit down before we part.

sreda@v-a-c.org

All rights reserved. Reproducing or using the materials from this web-page without written consent of the rightsholder is forbidden.