Anna Koleichuk

“Father in Wonderland”

V–A–C Sreda online magazine continues its three-month programme dedicated to the interrelation of art, technology, and landscape.

This issue publishes a conversation between Daniil Beltsov, editor-in-chief of V–A–C Sreda, and the artist and curator Anna Koleichuk—daughter of the architect Viacheslav Koleichuk, one of the pioneers of kinetic art in Russia. They discussed how mathematics and poetry are brought together in Koleichuk’s art, how self-stressed [tensegrity] structures function, and what is hidden inside the mysteriously named “gravitsappa”.

Daniil Beltsov: Anna, to my mind, engineering construction and art are closely interrelated in the artistic and architectural objects of Viacheslav Koleichuk. How was the process of interweaving different forms, methods, and ideas structured?

Anna Koleichuk: A whole study could be devoted to this question! I think it’s worth beginning with the fact that Viacheslav Fomich was an architect by education. In 1966, he graduated from the urban planning faculty at the Moscow Architectural Institute—the most favourable time for free artistic activity and experiments. The Thaw had a significant impact on the availability of information—it flowed in from everywhere. My father would recount how the architectural institute subscribed to a great number of foreign journals, and that the translation department would immediately translate them into Russian. Which meant it wasn’t even necessary for a student to know languages! It was during this period, in 1964, that Viacheslav Fomich became interested in innovative directions in architecture—in “self-stressed” [tensegrity—Ed.] structures.

Along with his peer Yuri Stolyarov, he created experimental engineering models that greatly impressed the teachers at the architectural institute. Sometime later, they were allocated an individual workshop—a small room under the stairs where over the course of a year they worked on their project, which proved a real discovery in the field of architectural forms. It is partly here that the answer to your question lies. Viacheslav Fomich was, first of all, a researcher, a man of science, which meant he was interested in the different facets and qualities of space.

It’s also important to recall The Newest Structural Systems in the Formation of the Architectural Environment, the book that Viacheslav Fomich wrote in 1973, when he was working at NIITIAG [Scientific Research Institute of Theory and History of Architecture and Urban Planning—Ed.]. If we open this book today, in 2024, we will be astonished by the extent to which the ideas set out in it remain experimental. Self-stressed, instantaneous structures, rigid structures, tent structures, grid structures, cable-stayed constructions. When the Newest Structural Systems was republished in 2016, copies sold out in an instant, and all the young architects I met would say in one voice: “All these themes are still relevant today.” This was remarkable, given a full fifty years had passed.

D. B.: But at what point did the turn take place, what Aristotle calls “peripeteia” in his Poetics, when Viacheslav Fomich realised he was an artist? It can’t be a coincidence that his architectural works exist not just in the scientific field, but become parts of exhibitions, gallery and museum spaces, and of GES-2 House of Culture in particular.

A. K.: My father once told me about how he asked his teacher: “We are constantly experimenting, coming up with new artistic projects, but no one will ever build them. What should we do?” To which his teacher answered: “Slava, do what you think is important, and nothing will disappear.” And it’s true, all you need to do is remember Ivan Leonidov or Yakov Chernikhov—the majority of their ideas weren’t realised, but they have remained in history. I think that for Viacheslav Fomich these words were the “turn” you asked about, a very important moment in his biography. He understood that meaning is embedded in the idea itself, and ideas can be embodied in absolutely different forms and situations—architectural, design, artistic. In 2017, for example, Viacheslav Fomich and I came up with the Architectural Mirages exhibition, which was entirely based on his ideas. On the one hand, these ideas exist in the artistic space, on the other, they could be made to scale and realised as architectural objects.

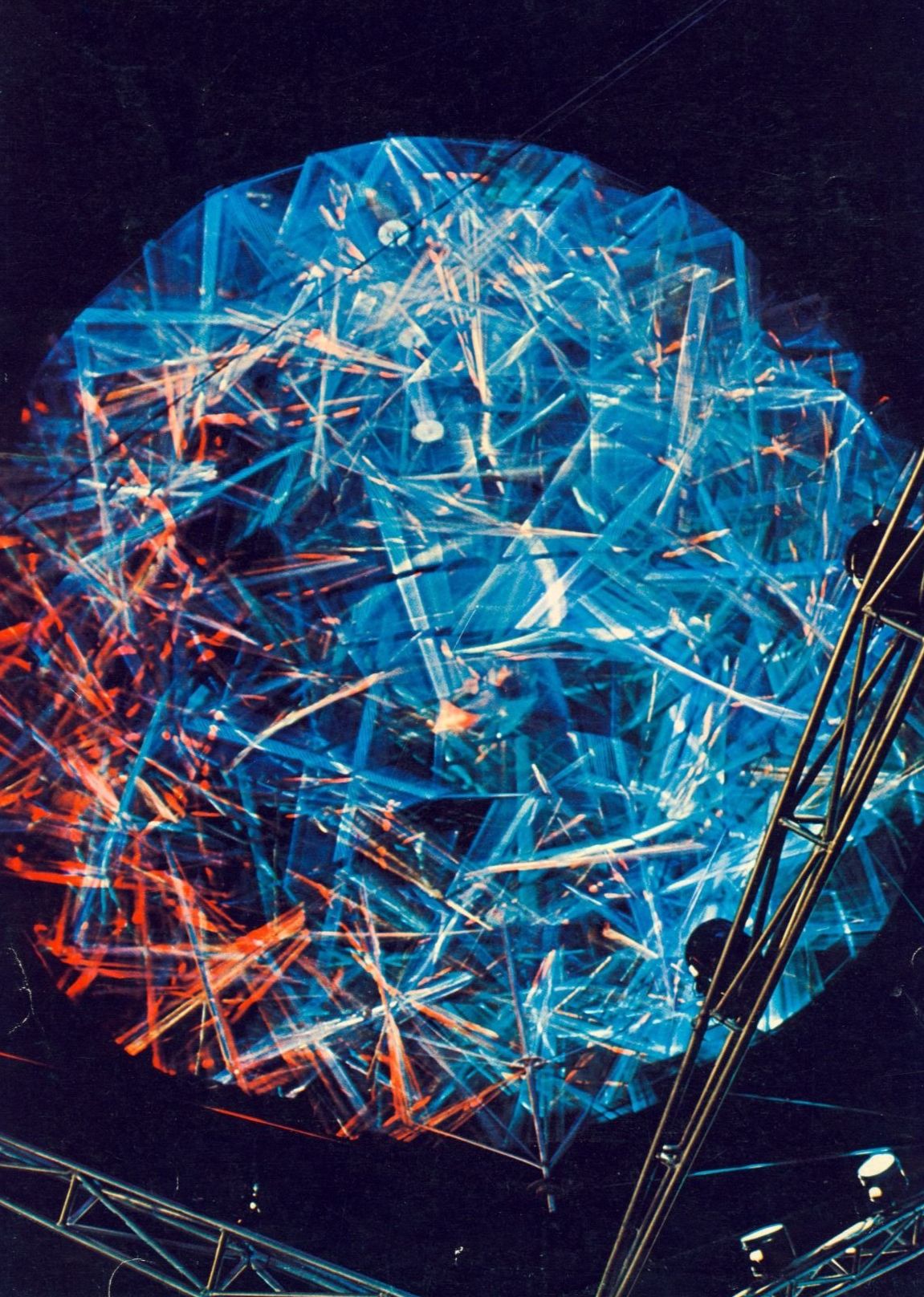

I think that the Dvizhenie [Movement] group [a community of artists working in geometric and metaphysical directions—Ed.], of which Viacheslav Fomich was a part, also had a significant influence on him. Some people say that Viacheslav Fomich was formed by Dvizhenie, but that, of course, wasn’t how it was. By the time he joined the group, he was already a graduate of the architectural institute and had patented the idea of self-stressed structures that lay at the basis of his Atom sculpture for the Kurchatov Institute. There are even photographs in which Konstantin Melknikov holds that stressed sphere in his hands. Which means that Viacheslav Fomich had found his path long before he joined the group. Dvizhenie rather gave him the idea that you can work in architecture and develop as an artist. I think the most important turning point lies in this.

D. B.: It would be interesting to see the photograph with Melnikov!

A. K.: It’s a rare photograph. We included it in the Living Line catalogue, which was published by the Tretyakov Gallery. In general, the works created in the period from 1967 until the end of the 1970s are kinds of manifestos, marking Viacheslav Fomich’s further development as an artist. Total theatre, various graphic and architectural concepts and models are woven together in them.

D. B.: Could you tell us more about these graphic models?

A. K.: And again a question worthy of its own monograph! I repeat that the period from 1967 to the 1970s is really very important, and that the manifestos of those times mark out Viacheslav Fomich’s artistic vector of development.

The conceptual graphic model of Total Theatre looks like diverging squares, like circles on water from a thrown pebble. These squares symbolise environments that intersect with each other and encode different architectural elements. And again to your remark about the motif of interweaving, unifying different forms—it can be traced through all of his works.

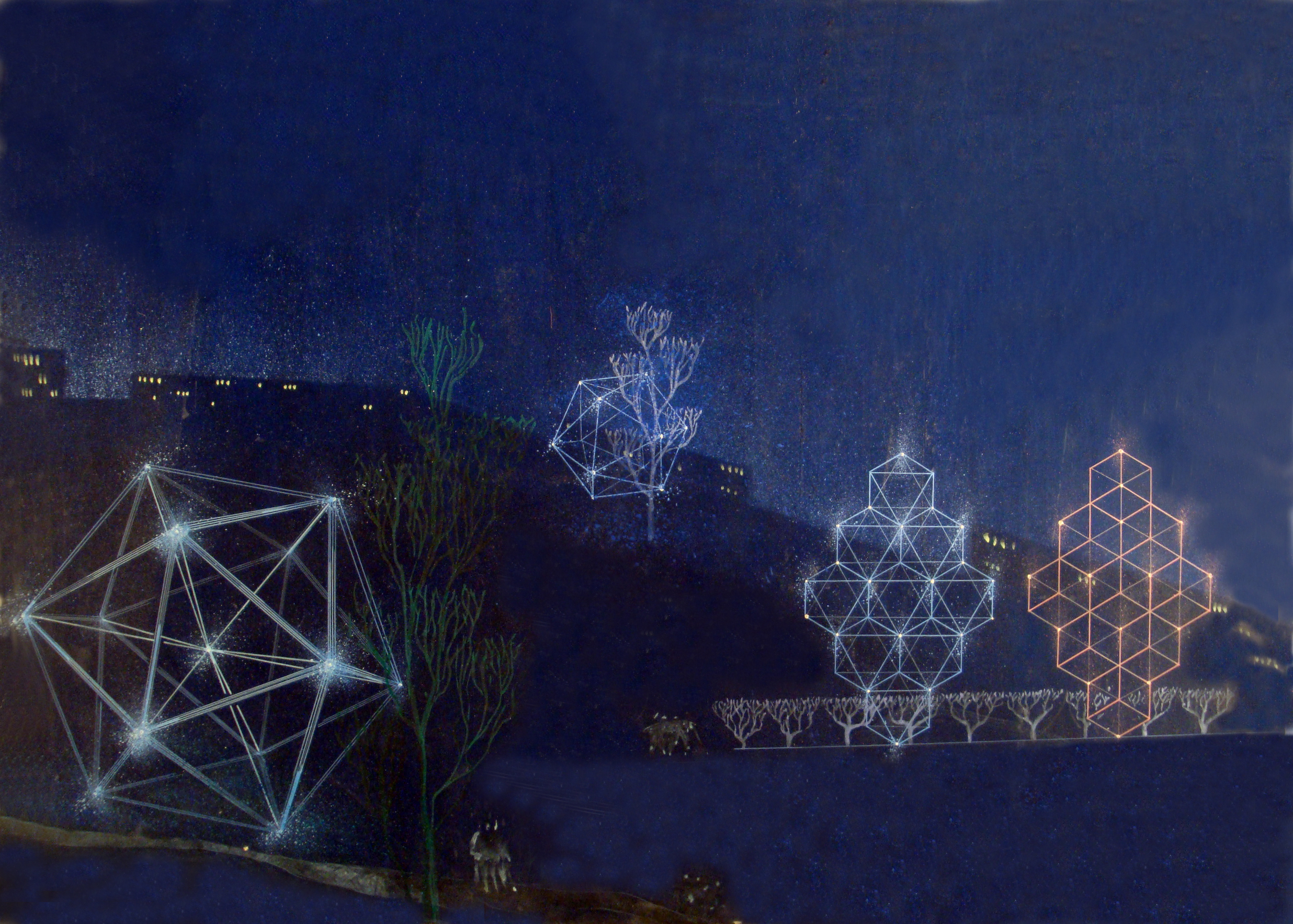

We can’t not mention another important project by Viacheslav Fomich—the Garden of Structures graphic diptych of 1968. On black paper with fluorescent paints, he painted a park landscape featuring different structures. According to my father’s idea, they were supposed to have existed like flowers. If the project had been realised, these structures were to have reacted to the sun—they would have bloomed to meet its rays during the day and hidden at sundown. On paper, in natural light, the viewer sees black and white graphics, but once the special fluorescent lamp is turned on, the flower-structures begin to glow in different colours.

Continuing our discussion of this period in Viacheslav Fomich’s work, in 1967, after his departure from the Dvizhenie group, my father formed the concept of a new group—Mir [Peace]. This group reflected a key principle for my father, about the world as unity, unification. I remember how my father would accept absolutely anyone, be friends with them, invite them to his workshop. The ability to gather maximally different environments around him was a foundational idea in his life. We are already touching on a human quality, but in fact the feature that you noted in Viacheslav Fomich’s art is inseparable from him as a person, like circles on water are inseparable from a thrown pebble.

D. B.: Yes! It seems to me that many features of art actually flow from the artist’s personality itself. When I look at Viacheslav Fomich’s works, I sense precisely what you were talking about—objects, environments, and forms do not disperse but, on the contrary, come together into a single whole.

A.K.: I remember that for me it was a real revelation to see in these remarkable constructions and mechanisms the embodiment of the world order. For example, Atom, which I already mentioned, literally symbolises the noosphere of the World: rigid elements are united by invisible threads and create a floating construction.

D. B.: I will note that the conceptual component of Viacheslav Fomich’s works ideally coexists with the beauty, the aesthetics of these objects. Also harmony!

A. K.: Here we really are crossing over to Viacheslav Fomich the artist. He has often been compared to a Renaissance man, because in these constructions strict systems and a scientific approach are remarkably united with art into a single formation. Once, I was handing over works to the Manege Central Exhibition Hall in Saint Petersburg and had to describe their technological and artistic components. Before me was no simple task: to convey the subtlety with which Viacheslav Fomich worked with materials, and, at the same time, a systematic approach.

D. B.: And how did you choose the words to describe the plastic appearance of the objects and what to lay emphasis on? It really isn’t a simple task: one the one hand, concept and theory, on the other, beauty and aesthetics, which require care, subtlety of formulation.

A. K.: It’s a particular challenge, because it’s always easier to talk about technology—you set everything out, and it’s done. But how can you talk about an artist?

D. B.: I understand you very well! If we generalise, simplify even, then technology is mathematics, and art is poetry. And poetry—which is elusive by nature—is really very difficult to talk about.

A. K.: Exactly, I can relate to this analogy. My note about Möbius was called: “How mathematics becomes art.” Here the main question is how beauty, incredible plastic form, is born from precise, strict science. I try to begin from feelings. I can read out a fragment.

D. B.: Yes, please!

A. K.: “Viacheslav Koleichuk’s Impossible Möbius sculpture plastically unites two mathematical models—Penrose’s triangle and Möbius’s strip. Paradoxically, the sculpture simultaneously contains three right angles and a continuous one-sided surface. Intellectual play and subtle plastic decisions create a full artistic image. Viacheslav Koleichuk experiments with spatial forms in his works. The scientific-research interest of the author is reflected in the precise proportions and harmonic volumes of the sculpture. In the bronze Impossible Möbius, as in other works, the sculptor brilliantly resolves the task set before him of making the weighty weightless. Fluidity of form, smoothness of line, and the arising sensations of movement for the viewer visually create a feeling of lightness and weightlessness.”

D. B.: I don’t have the sculpture before me, but it seems to me you were able to find the right words. The main thing is for the reader or listener to get an impression of Penrose’s triangle and of Möbius’s strip, of their plasticity—the images of “fluidity, ” the “weightlessness” in your text convey a sensation of movement.

A. K.: Yes, precisely the sensation of movement along the continuous line. Practically all of Viacheslav Fomich’s works can be approached from this point of view.

D. B.: One more curious object with a fantastical name is “Gravitsappa.” Could you tell me about this device and how it is related to cinema? We did a podcast in which we touched on this theme, and it would be interesting to learn about Gravitsappa from the inside.

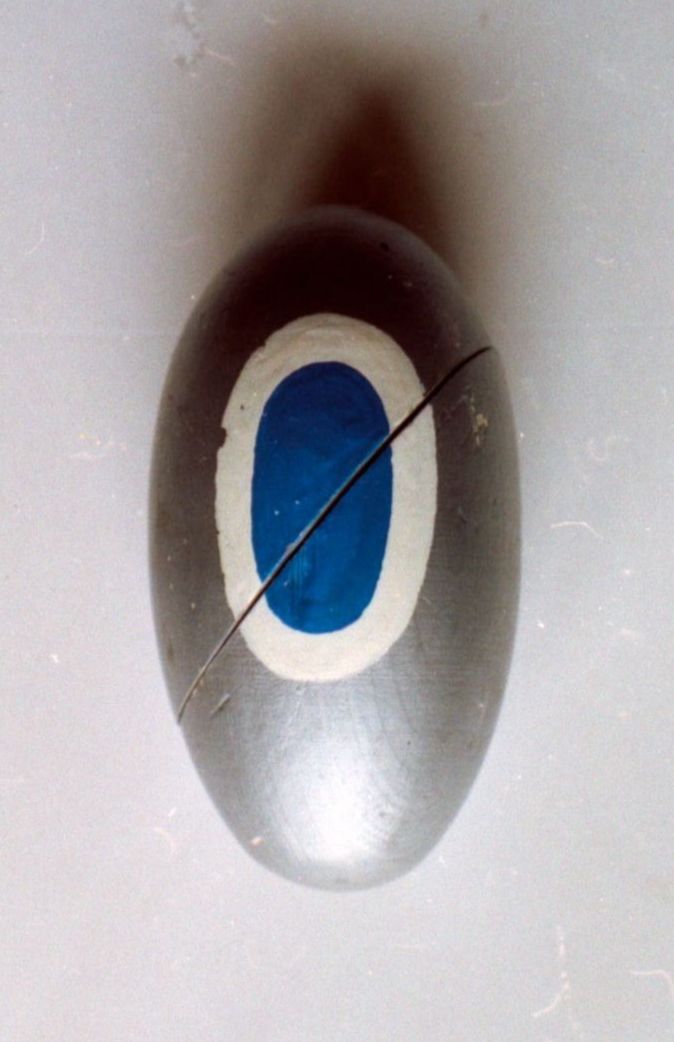

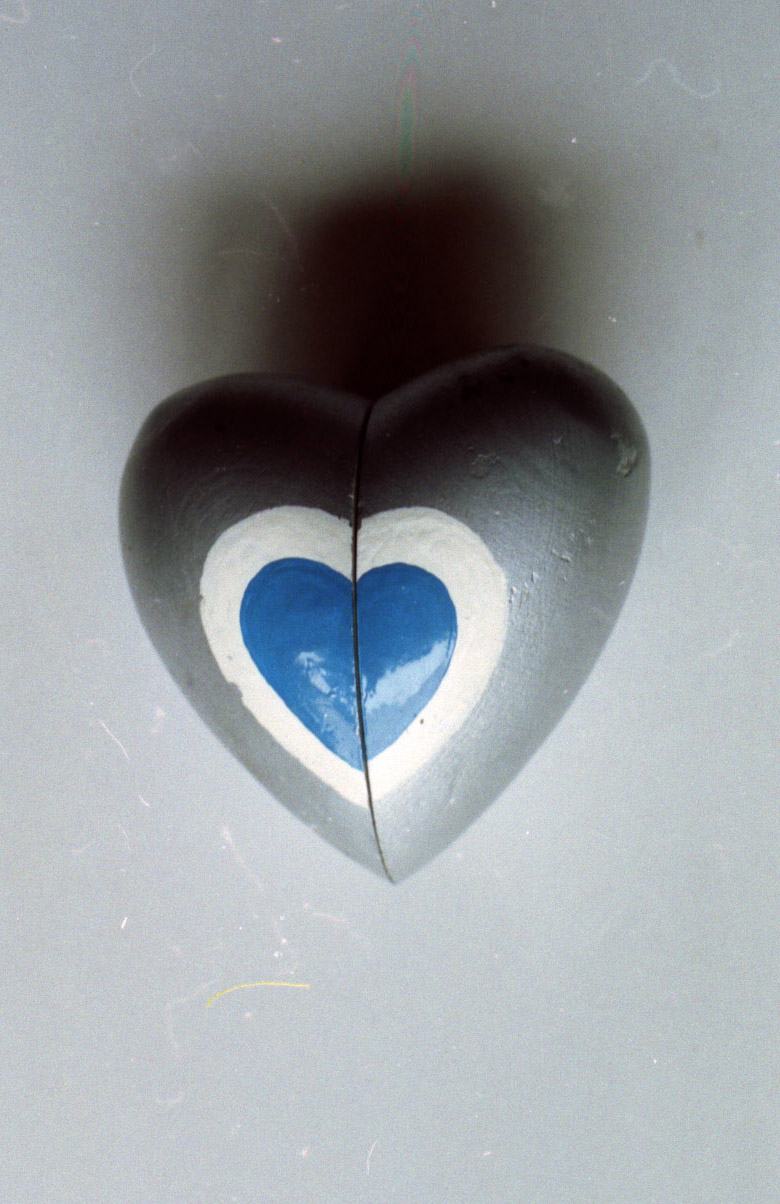

A. K.: It’s a funny story. Viacheslav Fomich developed a system of self-collage, in which a whole image is cut into small fragments, reassembled, and acquires an absolutely new internal space. Using this technology, he made a fairly ironic wooden object, Egg-Heart, which transformed into Gravitsappa—a moving metal device that became the central element in Georgiy Daneliya’s film Kin-Dza-Dza. One of his most famous works.

D. B.: Interesting convergences! When I first saw the works of Viacheslav Fomich, I began to think about space differently. Could you tell me about how he influenced your perception of art, were there any unexpected discoveries?

A. K.: I thought for a long time about a small project for an exhibition or book titled Papa, or Anya in Wonderland, in which I wanted to recount our life together and our shared stories. I spent a lot of time in his workshop, Viacheslav Fomich often involved me in his work or helped me with my own projects. I remember that when I was working on the costumes for a production of Victory over the Sun, my father helped me with a sounding costume—I soldered flexible strings onto brass plates on a top-hat and tailcoat, and Viacheslav Fomich showed me how to work with the soldering iron and rosin. The costume was very funny—it sounded, and added noise effects to the actor’s character.

We talked a lot with my father, and I always shared what I saw in his works. Once, I went to the Tretyakov Gallery to see Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square—a key work of the Russian avant-garde—and suddenly noticed in it a pixel, that is, an element from Grey Square, a little-known work by my father. I stood before this work and felt how the space before me was unfolding—raster grids of black and white squares literally came to life and moved. The idea of Grey Square lay in visual, perceptual distortions that appear at a particular distance. From up close, the encrypted elements are clearly visible, but all you need to do is move away a bit further and the little squares merge into a single grey figure. It was with this same technology that Viacheslav Fomich created his work YES-NO—from far away, the viewer sees the word “YES, ” but, coming closer, suddenly discerns “NO.”

Answering your question, Grey Square was that unexpected revelation for me, and turned my spatial thinking upside down. In 1998, I did the performance Matter at the Termen Centre. Images were projected onto a double screen, the first layer of which was transparent: black and white squares became larger, smaller, distorted, and finally scattered into separate elements. Space also became a plastic actor that interacted with parts of the performance—with images and the various planes of the screen. With Matter, you could say that the “Total Theatre” of Viacheslav Koleichuk, where experimental productions were created, really began.

But you know, talking about revelations, like talking about my father’s works, means reflecting on infinity. And that’s very important to me.

sreda@v-a-c.org

All rights reserved. Reproducing or using the materials from this web-page without written consent of the rightsholder is forbidden.