Tatiana Sokhareva

The Emancipation of Sound

V–A–C Sreda online magazine continues its three-month programme dedicated to the place, role, and transformation of sound in contemporary art and everyday life.

In this issue, we publish an essay by the curator and art and literary critic Tatiana Sokhareva on the interaction of sound and language. For a long time, sound was considered a “secondary” element, unrelated to the meaning of words, and philologists rarely studied auditory culture in the context of linguistics. Considering the methods of experimental phonetics, a discipline that emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century, Sokhareva demonstrates the agency of sound not only in the field of speech, but also in the poetic and musical experiments of the avant-garde.

“The emancipation of sound”—I chose so garish and pretentious a title in order to redraw the borders of the customary conversation about sound and auditory culture in the space of linguistic experiment. In its relations to language—and this is precisely the field that concerns me as philologist most of all—sound has never had a solid and unconditional basis. One is unlikely to be able to say what exactly served as the first cause of this disunity. Back at the start of the twentieth century, at the height of the technological revolution, when new sound recording equipment began to appear and be fine-tuned, along with the first institutions and reflections in the field of proto-sound studies, the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure put forth the following postulate in his Course on General Linguistics (1916): “It is impossible for sound alone, a material element, to belong to language. It is only a secondary thing, a substance to be put to use.” As a consequence, linguistic thought became attached to the idea of the “secondary” nature of sound, and to emphasise the arbitrariness of the connection between sound and meaning. In the end, this view of the connection was refuted, although far later than it ought to have been.

Today, quite a number of disciplines enter into the problematic and relatively young and versatile field of sound studies, and sound seeks to evade each of them to one or another extent. Evasion in the name of separation, alongside a borrowing of methodologies—this is how one might briefly describe the formation of sound studies through its interrelation with the discourses and disciplines that lay claim to an exhaustive understanding of auditory culture. And they form an impressive list, which includes physics and psychology, music and literary criticism, philosophy and anthropology, and many other disciplines.

The relationships between sound and language, as well as between sound and meaning, are slippery slopes in the field of sound studies. Philologists and linguists rarely go beyond the bounds of the category of sounding speech or, shall we say, sonorous poetry. Many phenomena—noise, rustles, whispers—evade academic cartography and remain beyond the reach of even the most thoughtful researchers, on a territory of which it might be said, as Nikolai Karamzin ironically wrote of Livonia in his Letters of a Russian Traveler (1797), that “it is no shame to pass through squinting.” It is, in other words, entirely fair to remark that upon entering a bordering territory, more often than not, an academic takes on the role of an ignoramus, while it would be logical, in such a situation, to flee hasty conclusions, and it is always better to be over-insured. And, nevertheless, experimental phonetics, which will be discussed below, appeared before experimental music and became, in fact, both the testing ground for probing the limits of sound and the impulse to its emancipation.

In this context, I am interested not so much in the concrete methods and instruments proposed by experimental phonetics as I am in the possibility of considering the discipline as a means of producing knowledge about sound in areas that usually fall beyond scope of sound studies.

In Russia, the founder of the experimental phonetics discipline was Vasily Bogoroditsky (1857–1941). Bogoroditsky developed the basic technologies of phonetic experiment, which led to a great number of highly interesting discoveries in the field of sounding speech and in the study of the nature of sound in general. The first practical laboratory of experimental phonetics appeared at the University of Kazan in 1884—two years before a similar institution was founded in Paris by the French priest and linguist Jean-Pierre Rousselot in 1886. The acoustic characteristics of the sounds of speech were at the centre of Bogoroditsky’s laboratory’s attention, and its materials were the Russian and the Tatar languages. This was, in fact, the first instance of what might today be termed an interdisciplinary institution—Bogoroditsky’s laboratory brought together psychology, physiology, and linguistics, and proposed precise methods by which to measure sound phenomena. These methods receive criminally little attention today—despite their admittedly somewhat archaic appearance, the influence of phonetic experiments on the literature and culture of the twentieth century was enormous.

The laboratories of experimental phonetics that appeared in Moscow and Leningrad in the years that followed studied the sound structure of language, intonation, and rules for the accentual articulation of phrases—right to breathing processes in phonation (for this, a pneumograph was used) and articulation, which was studied with the help of X-ray. Such a sound panopticon in many ways answered the spirit of the time, which was carried away by ideas of glottology, that is, by ideas about the origins of language and the search for its sound basis. In practice, these instruments made it possible to bring out the musical tones and sounds that compose human speech, to study the acoustic spectrum of vowels, and to connect sound and facial expressions—in a word, they laid the foundation of our understanding of the phonetic component of language. By and large, these conclusions can be considered a part of “sonic thinking”—an academic field that studies sound epistemic models through media theory, historical discourses, and the corporeal dimension of hearing. Sonic thinking is also committed to establishing connections between acoustic and cultural phenomena—including, among the latter, linguistic phenomena.

Adepts of sonic thinking, as a rule, call not just for thought about sound (about its cultural significance and content, for example) but for thought with sound and through sound. Angus Carlyle, Professor of Sound and Landscape at University of the Arts London, works in the space between the documentary and the poetic: he dedicated his essay “Memories of Memories of Memories of Memories of Memories: Remembering and Recording on The Silent Mountain” to field recording experiments in the south of Italy and to the relationship between sound art and memory. Carlyle asserts that sound has a memorial nature: it remembers its origins and carries with it the history of its own path. Such a fascinating metaphor leads to a reconsideration of not just the role of the sound artwork, but of the means of technical reproducibility which we are accustomed to use as empty forms for the recording of acoustic events. Actually, sound-as-memory finds itself in the space of barely perceptible noises, technical interferences, and lacunae, which a witness is not capable of conveying thoroughly accurately.

Although in its early stages, experimental phonetics did not plumb the ontological depths of this question, it enabled the revelation of the subjectivity of sound and pushed us to a broader understanding of the acoustic. Nevertheless, one not infrequently encounters affinities between experimental phonetics and sonic thinking: the linguist Lev Shcherba, another of the founders of phonetics as a discipline, called for the recording not just of concrete sounds, but of the “facts of the consciousness of the person speaking in a given language.” It is of no importance whether we use recording equipment or our own ears: “After all, even a keen ear does not hear that which is, but that which it is accustomed to hear, in conformity with the associations of its own thought.”

Perhaps the most obvious sign of the relationship between sound and language during the period of experimental phonetics’s formation as a discipline is visible in the literary works of the twentieth century. It is precisely during this period that sound became a fact of poetic language—in particular, Velemir Khlebnikov was among Shcherba’s students for a short time, when he attended the philological faculty of Saint Petersburg University. The discovery of phonemes, the smallest units of language, paved the way to the previously unexplored world of the inner structure of words and sounds—and from there, only one step remained to phonetic writing, and this step was taken by Khlebnikov, Aleksandr Tufanov, and Aleksey Chicherin.

Sound-painting as one of the strategies of zaum language in Khlebnikov’s poetic practice was aimed at overcoming the “arbitrariness” of the linguistic sign. His poem “Bobeobi sang the lips…, ” a fairly early experiment, has a phonetic structure and anticipates worldwide sound or sonorous poetry, indicating how a visual image can be born of a sound image (“Face”). Khlebnikov, in fact, was the first to enter the field of phono-semantics—he reflected the connection between a sound and its meaning, and searched for new sound characteristics of words that might allow for the recreation of language as a whole. The linguist and literary critic Roman Jakobson describes this as “a bright euphonic spot” in which: “old words become phonetically obsolete, and are erased from common use, and, most importantly, are perceived only partially in their sound composition.”

We’ll sing for you, Rodun,

We’ll sing for you, Byvun,

We’ll sing for you, Radun,

We’ll sing to you, Vedun,

We’ll sing for you, Sedun,

We’ll sing for you, Vladun,

We’ll sing for you, Koldun.

An emphasis on euphony was characteristic of Khlebnikov’s poetic language, but, basing himself on phonemes, the poet often went beyond the bounds of zaum—words and their meanings began to glimmer through the manifestation of acoustic nature. In the end, Khlebnikov went from sound ornamentation to sound-painting, which he defined as a “nurturing environment from which the tree of the world zaum language might grow.” His supersaga Zangezi (1920–1922) was based on sound-painting, as well as parts of Andrei Bely’s experimental narrative poem Glossolalia (1917) —another experiment in the study of the semantic nature of sounds, albeit more visionary than scientific.

Discoveries in the area of phonetic experiment also led the zaum-poet Aleksandr Tufanov to (proto-)sound investigations—using the “scientific writing” of transcription, Tufanov created experiments in the field of phonetic music and poetry. “I don’t employ the future, and I have turned away from the past, ” wrote the poet, “I am approaching an imageless sound poetry.” Tufanov constructed his experiments based on “auditory units of language”—kinemas and acoustmas—which lend structure to acoustic works. Tufanov’s system of sound symbolism was in fact the most developed from a scientific point of view, but was only used in rare cases in practice, as, for example, in his Disruptions cycle:

Snou shayle shuut shipish snou

Snouiship niip neychar snee

Shal’yu belosnezhnoyu vse solntse

Snova do vesennikh zor’ zakryto

(“Osenniy podsnezhnik”)

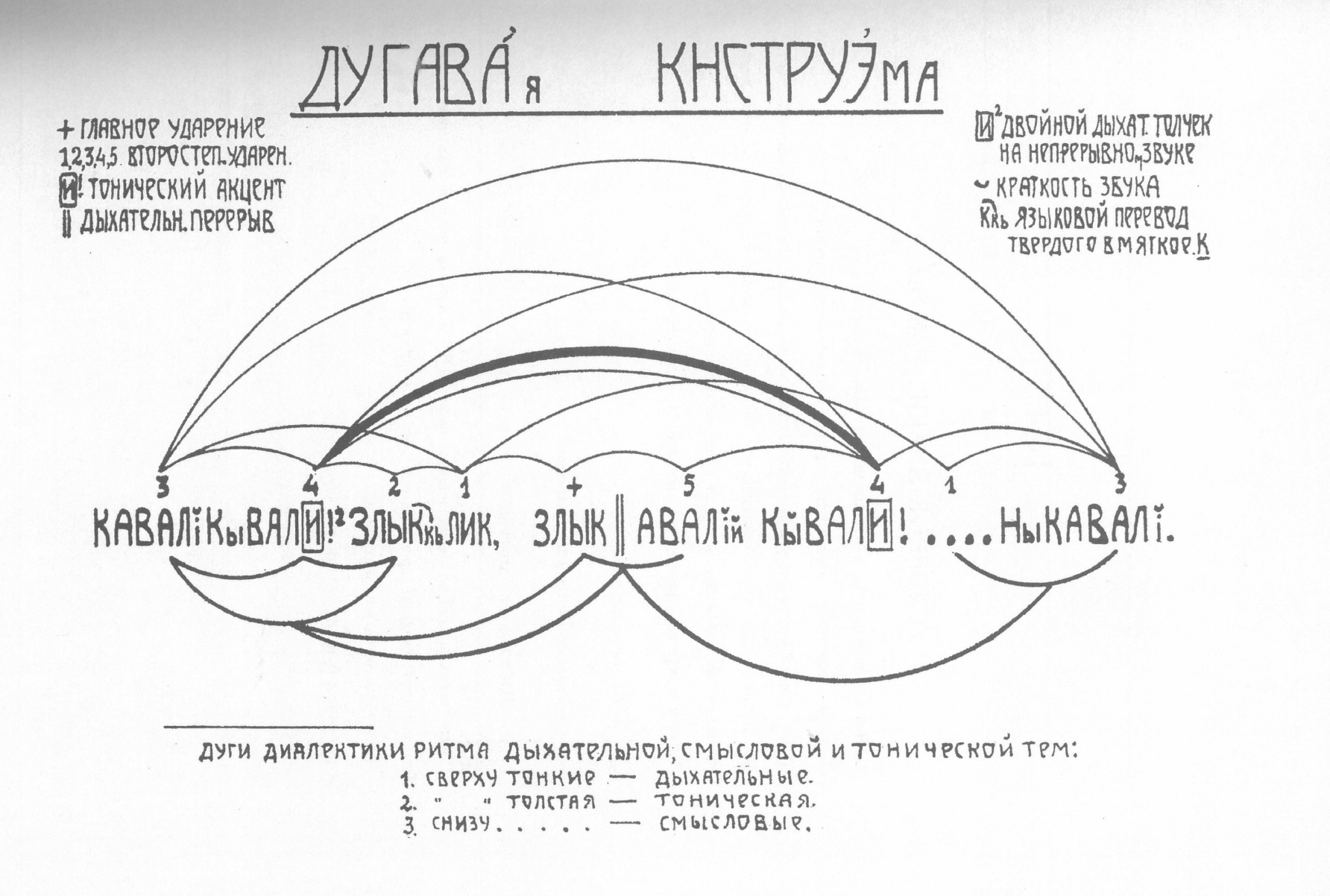

In the field of the interaction of the auditory and the visual, the most interesting experiments were those of the poet-constructivist Aleksey Chicherin, who in his work Kan-Fun (1926) put forward the idea of layering sounds “on composite soundings” and the elaboration of signs for the indication of “divisibility and duration, timbre, tempo, tonality, intonation.” These were experiments in the geometrisation of sound within poetic text. The phonetic basis of a word became a constructive element, which is clearly visible in Chichirin’s “konstruems,” many of which are furnished with precise instructions (his poem “LEDDEta; // CHemtBOLnZADEta…” is marked “Read aloud in Moscow dialect”). Expressive reading, deep listening, wheezing, onomatopoeia, and dialect become organic components of poetic language, widening both its possibilities and the field of sound experiment itself.

Contemporary sound theory considers this kind of part-writing as sound capture—equal to sound recording. There have been many experiments in this field, both from the side of poetry and from the side of academic music—note runs were used by Khlebnikov and Mayakovsky, while the composers Aleksandr Scriabin and Nikolai Roslavets included verbal material in their works. More important attempts at score notation from the point of view of sound and language were made by Daniil Kharms, who in 1934 composed Salvation, a cantata for four voices. However, in this work, there was no music notation as such, although rhythmic instructions were present, as well as instructions for reading-singing for a number of voices.

The next radical development was the inclusion of a corporeal dimension in sound works—from the experiments of John Cage (corporeal discomfort serves as one of the pillars of “4.33”) and the Fluxus movement—let us recall Yoko Ono’s performance-instruction Voice Piece for Soprano, that might fairly be described as a kind of sound gymnastics. Later, in the 1980s, the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy turned to the problem of sound proximity, for which the stay of the voice, vibration, and resonance were relevant questions, beginning with his essay “Vox clamantis in Deserto” (1986). Later, Nancy would add to his theses in his book À l’écoute, published in 2002, in which he explained how the body could be thought in the experience of sound and serve as a means of sound capture, existence, and dissemination. For the philosopher, who underwent a heart transplant and daily felt sound within and without himself, this was a highly existential experience, in the spirit of Edgar Allan Poe’s gothic short story “The Tell-Tale Heart” (1843).

The relationship between the sound of a word and its meaning is the cornerstone of dispute among sound researchers and linguists—until now, sound has been considered “arbitrary.” However, the first attempts to move beyond this vexing dissociation were made at the Phonological Department under the direction of Kazimir Malevich. The department existed for only half a year, from October to April 1924, but left behind materials that have not lost their relevance today—the treatise of the head of the department, poet, and theorist Igor Terentiev, for example (“There is no antinomy between sound and thought in poetry: a word means what it sounds”). In this period, Terentiev, Mikhail Druskin, Aleksandr Vvedensky, and Aleksandr Tufanov showed the interdependence of sound and meaning, paving the way for the development of a semantics of sound, which contemporary researchers continue to contend with today.

Today, it is onomatopoeia that is considered an argument against the ideas of de Saussure on the “arbitrariness” of sounds and their meanings: in particular, researchers from the University of Santa Cruz in California ran an experiment in which they asked students who spoke different languages to represent, with the help of sound, movement up and down, as well as words like “big, ” “small, ” “good, ” “bad, ” “fast, ” “slow, ” and so on. The results indicated that a speaker of one language was entirely capable of guessing the meaning of each word based only on sound. No gestures or facial expressions were used. The guesses of participants were founded on cultural understanding of sound and differed only in the most dissimilar linguistic groups—English variants were not entirely understandable to a speaker of Mandarin, and the other way around. All the same, sound symbolism is precisely that field where, in the words of Jean-Luc Nancy, the “subject of the subject itself” arises. Listening to a voice, a body, silence or resonance—we find ourselves.

sreda@v-a-c.org

All rights reserved. Reproducing or using the materials from this web-page without written consent of the rightsholder is forbidden.