Danila Ivanov

In Vino Veritas, or the Story of the Invincible Vine

V–A–C Sreda online magazine presents a special New Year’s issue dedicated to wine studies produced in collaboration with Danila Ivanov, a sociologist, wine researcher, member of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the Higher School of Economics, and participant in the GES-2 House of Culture grant programme.

We publish a text by Danila,, in which he describes a little-known yet significant episode in the history of winemaking: the attempts of Soviet scientists to create an independent foundation for viticulture, free from the European tradition, through the cultivation of the frost-resistant Amur grapevine. At the centre of the text is the breeder Alexander Potapenko, who demonstrated the viability of Vitis amurensis and made northern winemaking possible.

EXCESSIVE ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION IS BAD FOR YOUR HEALTH

Just imagine: from the 1950s to the 1970s, a Nobel laureate regularly travels to the Rostov region, to Novocherkassk, to drink wine; a special laissez-passer is issued to the Norwegian archeologist Thor Heyerdahl and his colleagues on the Ra and Kon Tiki expeditions for the explorers to become acquainted with the local wine avant-garde; later, Heyerdahl even becomes godfather to the son of one of the local winemakers. Artists also travel here, such respected faces of the USSR as the cosmonaut Mikhail Grechko and Boris Volynov—in a word, a true centre of gravity for bohemians from all over the world. Curiously, today in Russia barely anyone knows about this (even in expert circles), and a paradoxical situation arises: the team of The Oxford Companion to Wine treats the Soviet wine avant-garde with great reverence, while Russian researchers and public figures remain ignorant of it.

How did it happen that in the middle of the previous century, the Don steppes became one of the cradles of Russian winemaking? In order to understand this, we will have to begin from a bit further back.

For a long time, everyone in the world was certain that there existed only one type of vine suitable for winemaking—the cultivated Vitis vinifera, especially widespread in Europe and from which all the varieties well-known to us descend: Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Riesling, Pinot Noir, Sauvignon Blanc, and many others. In order to be “functional,” the grape must have a hermaphrodite flower: this way, it does not depend on pollination and gives a good harvest. Historically, there has only been one precedent for the appearance of such a grape thousands of years ago, and this was the “European” variety, although in reality it originated far from Europe, on the territories of present-day Georgia, Armenia, and Iran, on the banks of the Caspian Sea. This situation, in which only a single viticulturally suitable species existed, led to some pessimism, as future wines and grapes were in danger— Vitis vinifera can only grow on a small part of our planet, is threatened by many diseases, is extremely dependent on climate variations, and is vulnerable to fungi from other continents brought in by colonisation. This said, the products of the wine industry have a social role akin to wheat—they are not as noticeable in everyday life, but, in reality, it is thanks to them that many civilisations have formed and continue to form.

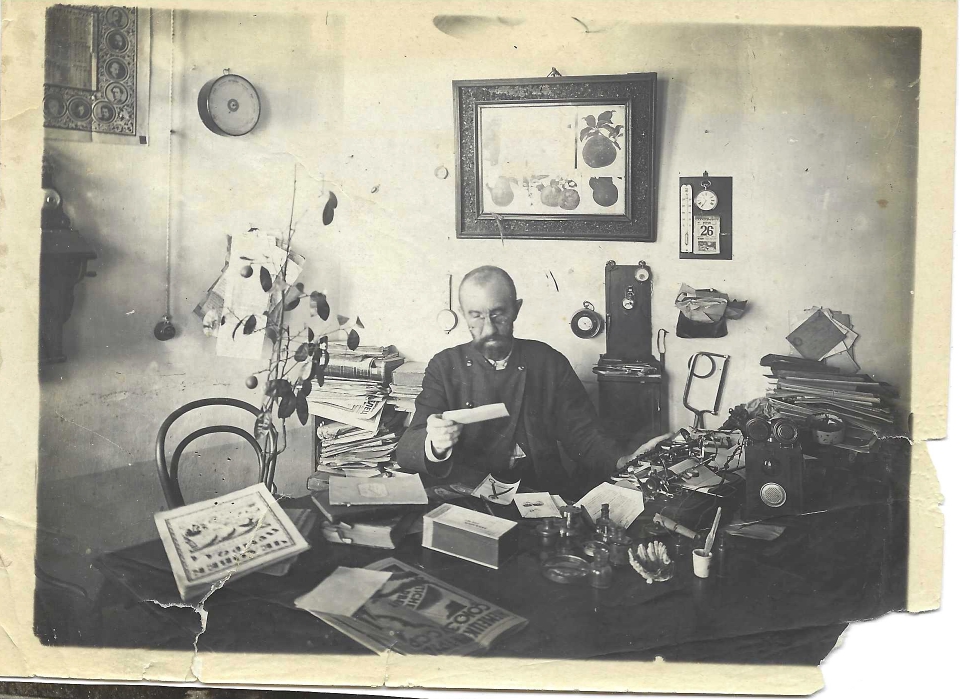

Ivan Michurin, a well-known Soviet biologist and plant-breeder, understood the problem well, and made attempts to transform European grapes into disease and frost resistant plants. At the start of the twentieth century, Michurin came up with a hypothesis: to strengthen the self-sufficiency of the USSR, one could theoretically sow the whole north of Russia with resilient crop that would not require black earth, but would be able to grow on sand, stone, and other “poor” types of soil. Among the contenders, alongside carrots and apples, were grapes. This idea wasn’t just strange but crazy, in as far as grapes, even in relatively warm regions such as Crimea, Krasnodar Krai, and the Don Valley, periodically died out either in winter or during recurrent frosts in spring. Yet, however strange this undertaking may have seemed, Michurin and the viticulturist Ivan Pavlovich (let’s remember this name) decided to take the path of specific hybridisation of plants and the systematic transfer of at least some beneficial properties. Hybridisation is the crossing of plants of different species, as a result of which the chance of achieving a new species with half the properties of each “parent” arises, though often in an average state. For example, if one plant has a frost resistance of 0°C), and the second –10°C), the new species will withstand temperatures of –5°C). (It’s important to note that hybridisation takes place only between plants of different biological species, and not sorts; the difference between sorts is like the difference between different breeds of dogs, while the difference between species is already the difference between a tiger and a lion, between Homo Sapiens and Neanderthal). In short, one species includes different sorts, one sort includes different species.

However, let’s return to the history of Soviet grape experiments, which took an absolutely unforeseen turn at the start of the 1940s when Moiseyev, a stone fruit specialist, discovered an unusual vine of the Vitis amurensis species in the Amur taiga, which, over the course of evolution, probably having lived through the Ice Age, had developed a frost resistance of –40°C).

The vine was immune to the diseases and fungi of American provenance that had plagued European winemakers since the beginning of the nineteenth century—it had grown on the shores of the Pacific Ocean, across which spores and diseases reached Eurasia and, over millennia, naturally developed immunity. What was most important, however, was that the vine was hermaphrodite! In the science of the time grapes of this species had already been described, but no one had imagined that they could be hermaphrodite. This meant that the vine wasn’t just a chance to turn all the northern territories into winemaking regions—it gave Russia the opportunity to become a wine country, with its own variety of grape.

It was not just a revolution in global winemaking that was visible on the horizon, but the symbolic transformation of the USSR into an independent state, not dependent on the capitalist “European” winemaking tradition. One fact lent especial drama to the situation: a significant portion of European vines of the Old World and Russia had been had been grafted onto American roots after the phylloxera epidemic, and “American roots” in Russian soil was a particularly sensitive subject for certain Soviet officials. The discovery of the hermaphrodite Amur vine was noted by prominent scientists, in particular by Alexander Negrul—a Soviet biologist of world renown, who is still cited today by international scientists. An expedition headed by the famous ethnographer Genrikh Anokhin set out into the taiga.

The vine was preserved, propagated, and, in 1947, sent for detailed analysis to the Institute of Viticulture and Winemaking in Novocherkassk, where an unpleasant discovery was made. The “discovered” species was just an American vine (Vitis labrusca) that had accidentally ended up on the taiga. Vitis labrusca possesses similar frost resistance and disease resistance, but is fairly unpromising: it cannot be used to attain the variety of either “table” or “viticultural” (technical) grapes.

The “discovery” was thenceforth perceived as a humiliating case and the cultivation of the “Amur” vine was rolled up, in as far it turned out to be an American hybrid incapable of achieving the ambitious goals. The “pseudo-Amur” vines were uprooted, and the dreams of northern winemaking remained dreams… But, perhaps, they were still destined to come true?

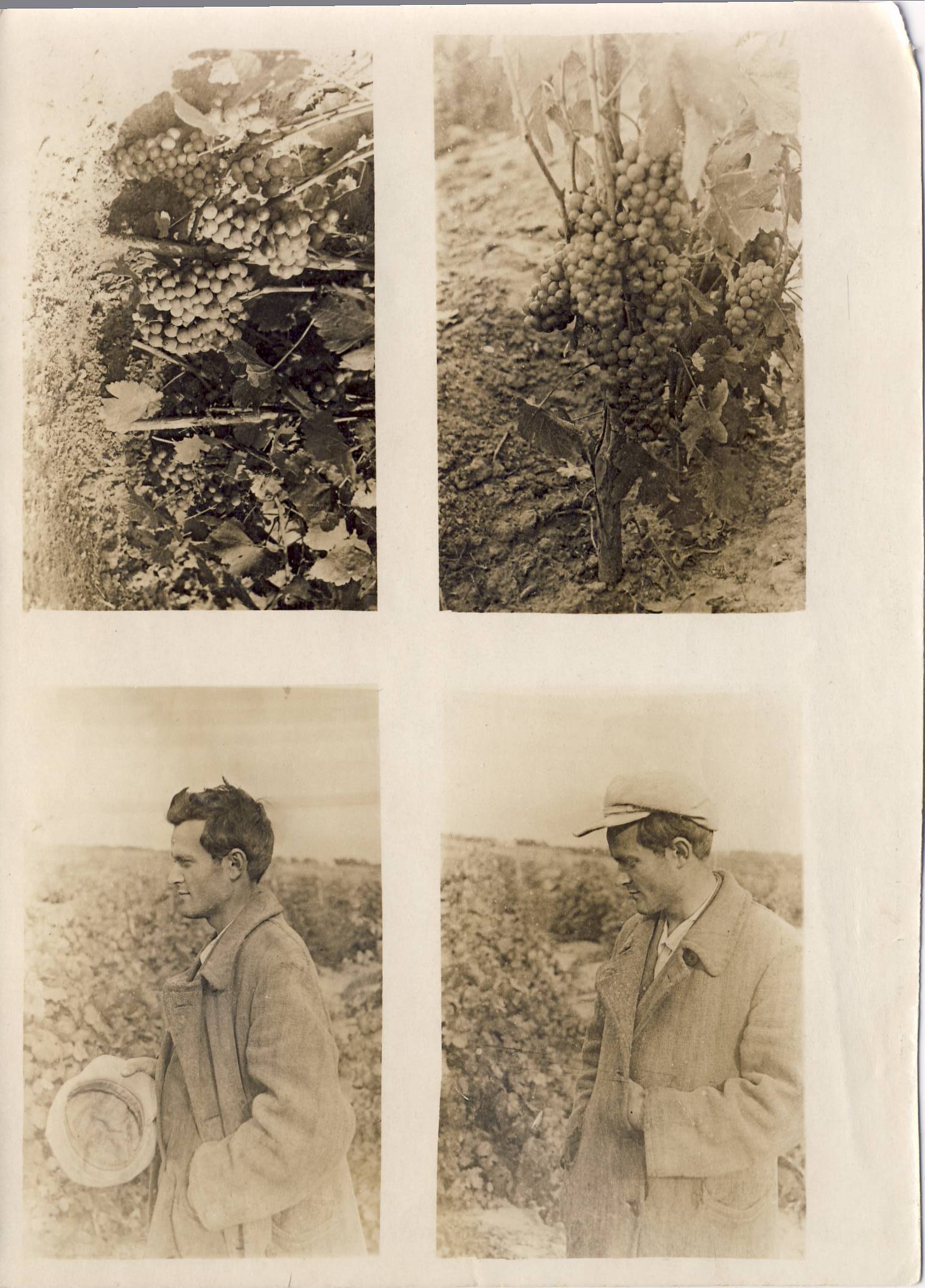

In 1934, long before the scandal described above, an article appeared in the Young Naturalist magazine about the twelve-year-old Alexander Potapenko, who, at the behest of his teacher Ivan Michurin, had created his first hybrid, crossing the Amur vine and the Malingre variety. Two years later, the experiments of the young breeder, his father, and his elder brother led to the development of the avant-garde “Severny” and “Zarya Severa” varieties, and Potapenko decided to dedicate the rest of his life to the Amur vine and the fight for its future, for the future of northern Russian winemaking. He would later discover that the unique Amur grape had been mistakenly considered an American hybrid.

As the scientist explained, the discovery of the hermaphrodite “Amur” grape dates to 1932, when, during a conference in the Far East, the horticulturist Florya heard from the scientist Ramming that the Amur vine is always single-sex and objected—a hermaphrodite vine grew on his plot. Ramming did not believe Florya, and bet him a bottle of cognac, which, as we understand, he later presented to his opponent. The discovery, however, did not become widely known until the aforementioned stone-fruit specialist Moiseyev claimed it for himself. He transported grape seedlings to the experimental station near Vladivostok when he understood that the discovery would help him make a name for himself. Carrying out the propagation of the Amur vine over a long period, Moiseyev failed to isolate the vine during flowering, which led to unexpected cross-pollination with the American vines.

After the miraculous discovery of the vine described above, it was taken to Novocherkassk for testing, and this was no accident. Yakov Potapenko, the elder brother of Alexander, worked at the Institute of Viticulture and Winemaking, and was rapidly ascending the career-ladder—he had been promoted to a leadership position by Michurin himself. The Soviet biologist understood that no one knew northern grape varieties better than Potapenko. His confidence in this was reinforced by many years of collaboration with the viticulturist Ivan Pavlovich (do you remember him?)—again—Potapenko, the father of Yakov and Alexander. Yet Yakov Potapenko could not confirm that the discovered grape was truly unique—the contamination of the biomaterial was too severe.

However, his brother Alexander did not doubt the existence of the hermaphrodite Amur grape, and, given the opportunity, set about single-handedly re-checking the material sent from Novocherkassk. A great deal of effort was expended on saving the hermaphrodite vines in Vladivostok, which were being destroyed. In the end, Alexander discovered that the vine did exist after all, and this meant that Russia would have its own grape, and the country would give the world northern winemaking.

This discovery inspired Alexander, who, alongside everything else, also had exceptional artistic talent, to create the emblem of the Novocherkassk Institute of Viticulture and Winemaking—a “northern tree” (a birch) entwined by a “southern” grapevine growing from the snow.

Alexander’s breakthrough in the possible cultivation of the Amur vine, in conjunction with Yakov’s research into interspecific hybridisation of this grape with European grapes, made Novocherkassk the most important “wine destination” for bohemians from all over the world. And here we return to where we began—the golden age of Don winemaking.

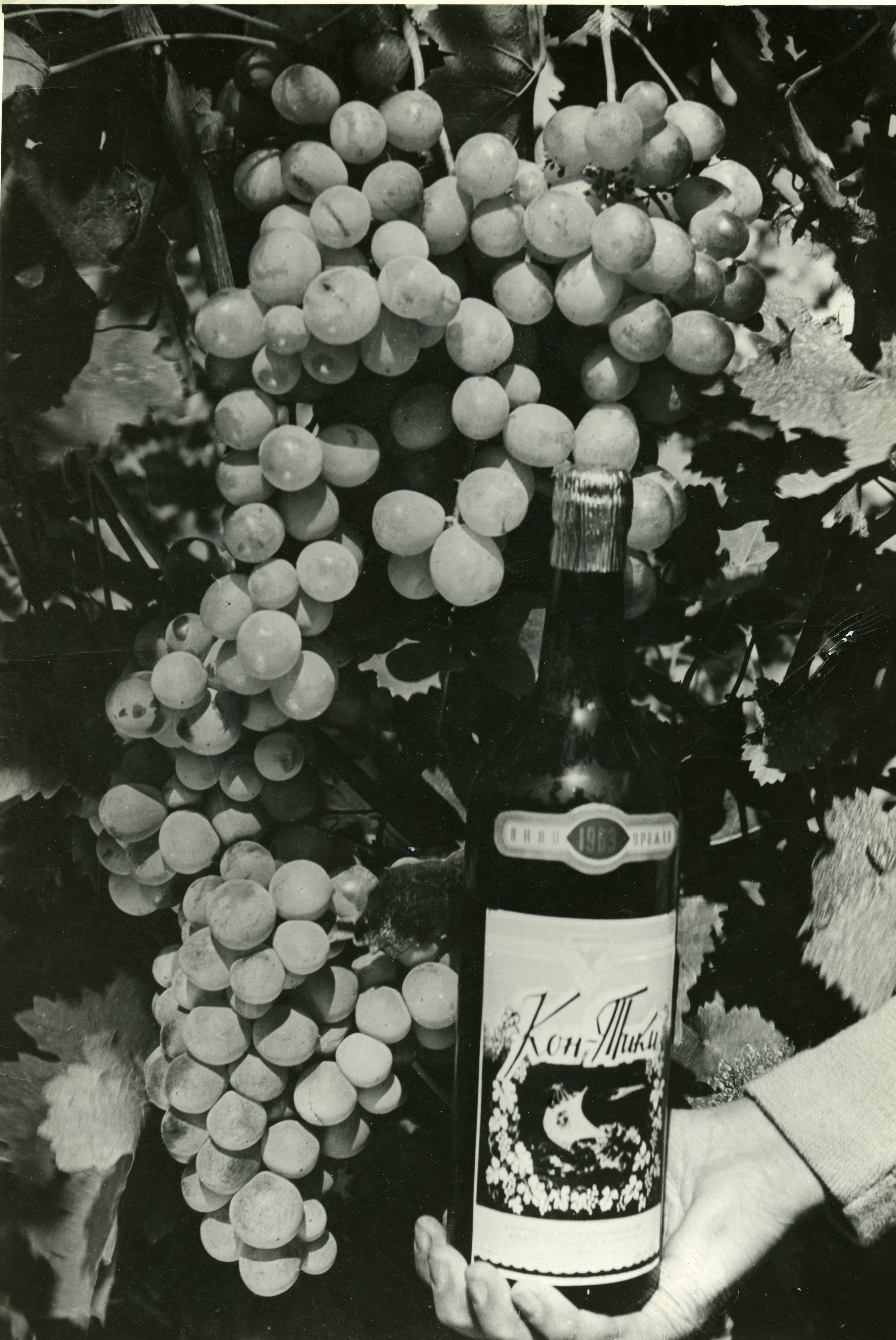

The Soviet discoveries were noticed by Italian and German scientists, and they began to travel to the USSR; Thor Heyerdahl became interested in “northern wine.” He began a correspondence with Alexander Potapenko, and this was the beginning of a long friendship between the Soviet breeder and the Norwegian explorer: later, Heyerdahl would become the godson of Potapenko and chose a name for him—Arne, and Potapenko would dedicated a number of his varieties to Heyerdahl: “Kon–tiki,” “Tur Heyerdahl.”

The Nobel Laureate Mikhail Sholokhov was also a frequent guest at Novocherkassk, and even had his own room at the winemaking institute. Interestingly, after a number of Sholokhov’s visits, the management of the Institute received an order no longer to accommodate the writer, as it seems that, after Novocherkassk, he had been in a bad way for a long time.

One more area of interest for Alexander Potapenko was the description of the biological and cultural history of the grapes of the Rostov oblast. The scientist discovered evidence of roots dating back millennia on the territory of Russia, and connected this to the Khazar Khaganate—this work was noticed by Lev Gumilev, an ethnologist and historian, with whom Alexander began a debate and then a friendship.

Nevertheless, there were plenty of problems. Continuing his work on the cultivation of Amur vines, Alexander Potapenko gradually understood that the quality of seedlings could have been better, and that the seedlings brought from the Taiga did have the necessary flavour characteristics. It turned out that during the expedition, vines with berries had been selected, and the sweetest fruits on other vines were simply pecked by birds. In his turn, Yakov Potapenko faced pressure from above, as not all orders and plans for viticulture were realistic; at one point Yakov was in conflict with Trofim Lysenko, a biologist known for his pseudoscientific theories. The 1970s and 1980s were a particularly difficult period in the history of the Potapenko family—Yakov died suddenly in 1975, a year later, Alexander left Novocherkassk, taking some of his cultivations with him, having been unable to find a common language with the new management of the Institute. The state’s fight against alcohol only intensified—and this put an end to important viticultural and wine discoveries.

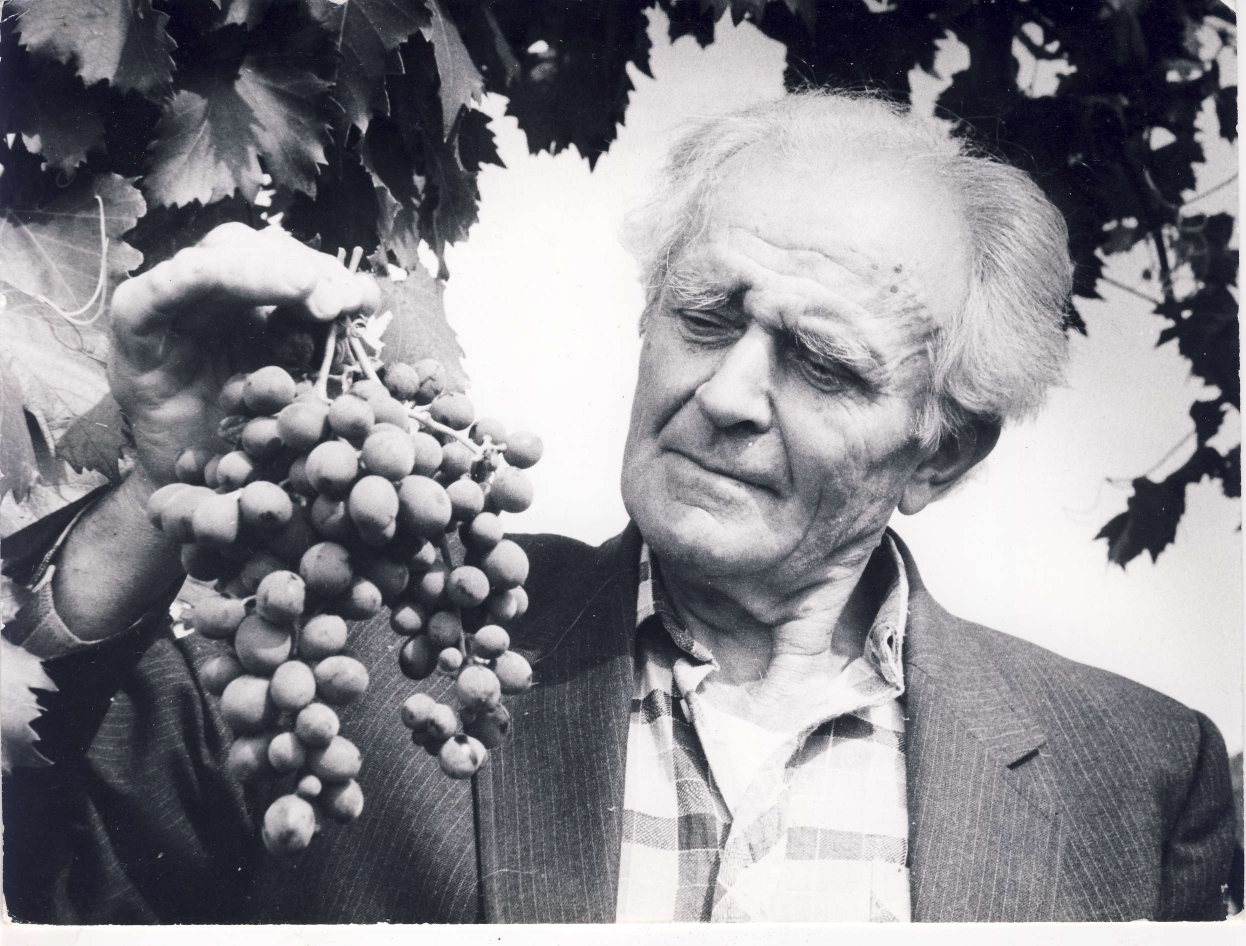

Alexander Potapenko found a new home in the village of Oleyni in the Volgograd region around 1980, where, despite poverty and oblivion, he continued his experiments with the breeding of Amur vines and hybrids, and created at least seven of the first varieties of the Amur grape: “Amur Potapenko-1,” “Amur Potapenko-2,” “Amur Potapenko-3,” and so on. The “Seventh” variety is also known as the “Amur Breakthrough” or “One.” Some of the grapes created by Soviet enthusiasts are used today by major producers, whose wines can be found on the shelves of almost any supermarket.

Potapenko’s work clearly proved winemaking is possible even in the northern latitudes. His success and the success of his brother lay at the foundation of many winemaking projects across all Russia—from established initiatives in Volgograd to relatively new projects in Saratov, Moscow, the Moscow area, and even Tver, where the Hieromonk Thaddeus makes wine on a monastic island in Lake Seliger. Many of the varieties established by the Potapenko brothers, such as the “Flower” variety (known in Europe as Blütenmuskateller), as well as the “Northern” and “Early Violet” varieties, and dozens of others, laid the foundation for modern varieties that make winemaking possible in regions with complex climates. Thanks to these hybrids, whole industries have appeared in Switzerland, Germany, Scandinavia, Great Britain, and China. It’s hard to believe this today, but the pioneer of the northern wine avant-garde Alexander Potapenko died unknown in 2010. And in 2025, his wife Ludmila—Potapenko’s colleague in his breeding work, the editor of his books, and the keeper of his home—also passed away.

Yet certain artefacts preserve the memory of Potapenko and his wild project today—from time to time, in the forests of the Volgograd and Rostov regions, almost extraterrestrial varieties of the Amur grape unknown to anyone are found, and an attentive buyer can find the surprising names of the “Potapenko” varieties on the back labels of certain Russian and foreign wines. One more testament to the most important epoch in the history of Russian winemaking is provided by the wine labels created by Potapenko. These works are distinctive artefacts of Soviet graphic design, where Mannerist sophistication, Lubok simplicity, and eclecticism are fantastically combined. In fact, each label is an encrypted narrative, playing not only on events in the winemaking world but on Potapenko’s personal biography, his fantastic view of the world. This “idiosyncratic” perspective is carefully woven into the drawing and composition, becoming understandable only to those who know about the life and fate of their creator.

sreda@v-a-c.org

All rights reserved. Reproducing or using the materials from this web-page without written consent of the rightsholder is forbidden.